Thomas Jefferson wasn’t trying to pull the wool over anyone’s eyes when he directly borrowed John Locke’s ideas and language to declare the principle of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But, by definition, we could call what he did plagiarism.

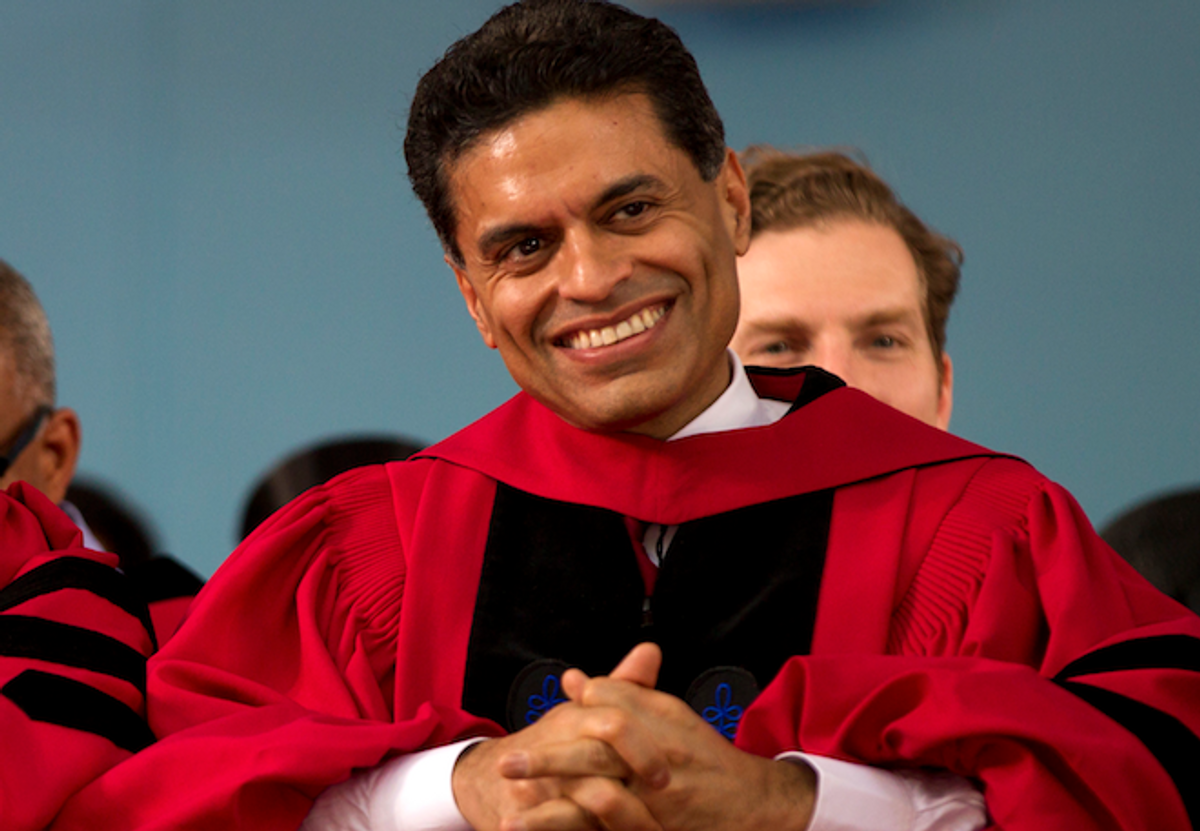

The major moral lesson to be taken from the Fareed Zakaria scandal is not what the media focused on this past week. Yes, he lifted material concerning the long, mostly unknown history of gun control, and he did so transparently. Even if he hadn’t been obliged to come up with an article for Time on a short deadline, he would still have taken more or less the same steps, and for a reason that, on the surface, makes perfect sense: The history he needed to tap into was too involved for someone trained as a journalist to investigate in depth.

Michael Barthel’s probing piece in Salon about transparency and credibility in the Internet age aims at the heart of the problem. But for professional historians, there’s more to it than the cut-and-paste freedom that the Web invites. Plagiarism is both a broader and touchier issue than most people imagine it to be – outright “copying.” It is ultimately a question of originality.

Frankly, we in the history business wish we could take out a restraining order on the big-budget popularizers of history (many of them trained in journalism) who pontificate with great flair and happily take credit over the airwaves for possessing great insight into the past. Journalists are good at journalism – we wouldn’t suggest sending off historians to be foreign correspondents. But journalists aren’t equipped to make sense of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Let this be, then, the tale of two highly visible Harvard Ph.D.’s who have been caught red-handed committing plagiarism. Both Fareed Zakaria and Doris Kearns Goodwin were awarded degrees in government from Harvard, 25 years apart. Goodwin, the elder, is a serial plagiarizer who has been welcomed back with open arms by the TV punditocracy. She directly and egregiously lifted quotes from others’ works on multiple occasions – a Pulitzer Prize–winning book contained passages plagiarized from three different writers! – and she quietly paid off one aggrieved author.

The full story can be read in University of Georgia historian Peter Hoffer’s book "Past Imperfect" (2004). It’s damning. It’s also revealing of the fact that Goodwin recycles material because it’s easier than coming up with something new. Bear in mind that, as a matter of course, history majors are taught to visit the archive and focus on primary sources. Government majors are not. Still, that is no excuse for what she (or Zakaria) did.

Even as she admitted to slipshod research in 2002, Goodwin rounded up her prominent journalist friends – and she even co-opted some professional historians. They published a letter in the New York Times assuring the public that she was a writer with “moral integrity” who was innocent of plagiarism. She disappeared from TV and, until her infamous fraud could be erased from public memory, put off publication of a new, breezily written, but still unoriginal (if plagiarism-free) book.

That book was the big-buzz-generating "Team of Rivals." It was allowed to surface because her publisher was deeply invested and celebrity authors are good bets. Media conglomerates don’t care if the star author is flawed or historically sloppy. Literary larceny is acceptable if the bottom line is helped. The cloud lifted – boy, did it lift – and she was fed prestigious book prizes all over again, returning to prime-time with a vengeance. We’ll grant that, as an engaging public personality, she knows something about the modern age. But when it comes to an earlier America, she has to rely on paid researchers and real historians for legitimate ideas. Where’s the genius in that? Yet everyone will tell you she is among America’s very best historians.

Second best, actually. The beloved David McCullough, formerly of Sports Illustrated, is routinely enshrined as “a national treasure” and “America’s greatest living historian.” But nothing he writes is given real credibility by any careful historian because history is grounded in evidence, and McCullough isn’t familiar with more than a smattering of the secondary literature on most subjects he tackles. He hires a younger researcher (the Goodwin method) to read for him and tell him what’s important. If he doesn’t read in depth the books and articles he lists in his very thorough bibliography, which someone else presumably compiled, how honest is he being with the reader?

What makes him a historian? It's his avuncular personality, not any mastery of the sources.

Though more than a million copies of his book "John Adams" sold, even more Americans were influenced by the HBO series of the same name, which was marketed as if based on the book. In reality, not only was the history grossly distorted, many of the scenes were stolen from "The Adams Chronicles," which appeared on PBS in the 1970s. There are far better books on Adams than McCullough’s, but they haven’t been hyped. There's no money in it. History is hard to sell if it’s complicated.

We have to fight mediocrity as well as plagiarism – the two are more closely related than you realize. Journalists doing history tend to be superficial and formulaic. To the historian’s mind, they don’t care enough about accuracy. It’s a surprisingly short distance to travel from dressing up the past in order to make it familiar, to paraphrasing (actually, stealing) an earlier biographer’s ideas.

History is not a bedtime story, folks. Plagiarism is variously defined as “wrongful appropriation” and “close imitation”; it is not just blatant theft of the gist of a paragraph. Originality in writing history is something palpable and verifiable, and it’s the reason History Ph.D. candidates spend years researching and writing a dissertation, taking several years more to fashion it into the book that will earn them tenure. Good history demands the ability to judge the available evidence – a form of knowledge journalists are not asked to cultivate.

Most everyone who transgresses on the work of historians uncritically accepts someone else’s work, then tweaks it a little. That’s how the game is played. But historians are trained differently. They are taught to be suspect of authors who come to their information secondhand. The mark of a good historian is writing something new about something old and making an original argument gleaned from primary sources.

You will not find a painstaking scholar dressing up his or her material to make it more familiar than it should be, such as: “The dark eyes that gleamed behind large metal-rimmed glasses – those same dark eyes that had once enchanted a young officer in George Washington’s staff – betokened a sharp intelligence, a fiercely indomitable spirit …” This is from the opening page of Ron Chernow’s mega-selling "Alexander Hamilton," describing Hamilton’s widow as if the author knew her personally and could verify these superior qualities. Chernow is a smart guy; he's another Ivy Leaguer who rose from freelance journalism to become a Pulitzer Prize–winning popular historian. His bias in favor of his subject is akin to McCullough’s, though he writes better and goes deeper.

You will not find a careful historian citing the work of someone whose face is on TV above the made-up title “Presidential Historian.” That’s done to give the appearance of authority when there is not the substance of it. But there are still bigger frauds in the History marketplace. Bill O’Reilly’s "Killing Lincoln" is a national bestseller? What could be more pathetic than to look for a single original idea in such a book? Yet it isn’t called plagiarism.

The careful study of history does not yield a litmus-test slogan on the order of “We’re an exceptional nation.” It’s no wonder that you have Paul Ryan this week declaring his intention to “go back to the founding principles” and other congressional Republicans fatuously claiming that the founding fathers promoted small government, and therefore so should we. Sure, the founders’ America was a small country. They were not legislating for 315 million people. Thomas Jefferson’s entire State Department employed fewer men than it takes to field a baseball team. But this is the kind of logic you get when you get your history from inspired cheerleaders rather than professional historians. It’s what you get from the constant recycling of old stories, thefts from older books – most of which is never caught. The perpetrators not only go unpunished; some are lionized as the nation’s most noteworthy historians.

The trend will no doubt continue. The public seems to like what is most easily digestible, especially if it comes from the word processor of someone congenial whom they regularly see on TV. And publishers know they can successfully market a book from a household name, no matter how derivative its content. Name recognition trumps quality. Appearance is everything.

Shares