Why is there no pro-business conservatism in America? At first the question might come as a surprise. After all, conservative thinkers and politicians pose as champions of the private sector.

But in reality, the economic agenda pushed by the American right benefits chiefly “rentiers” or investors — the minuscule number of individuals who are wealthy enough to live on streams of income from their investments. An alternative pro-business conservatism would find many points of agreement with the center and center-left — and would be strikingly different from today’s American right.

The prevailing economic theory of the American right is that economic growth is driven by investment; investment is driven by capital; and rich people own a disproportionate share of the capital. Therefore, cutting taxes on the rich will lead directly to more investment within the United States, which in turn will lead directly to more broadly shared economic growth in the United States. This supply-side, trickle-down theory provides the rationale for Paul Ryan’s plan to eliminate capital gains taxes completely.

The theory is flawed in many ways. To begin with, conservative trickle-down economics exaggerates the role of rich individuals in investment, much of which is funded by the retained earnings of companies. Trickle-down theory also ignores the importance of the pooled savings of non-rich Americans in 401Ks and employer pension plans.

An even greater problem with this theory lies in the assumption that increased after-tax income for the rich will be translated automatically into increased investment. The rich may not invest their money in productive enterprises at all. They may spend their money on what Thorstein Veblen called conspicuous consumption. They may hoard their money. Or they may invest it in enterprises that provide them with a steady return but contribute little or nothing to productivity growth — for example, casinos of the kind owned by conservative donor Sheldon Adelson.

There is another flaw in the conservative economic theory. In a global economy, there is no guarantee that rich investors will invest the money they save from tax cuts in productive enterprises in the United States. They may invest in factories in China or the energy sector in Brazil. In such cases, tax cuts for the American rich will spur investment in other countries but not the U.S. And even if investment-driven growth occurs inside U.S. borders, most or all of the gains from growth may go to the few, not the many, as in the last generation.

It is possible to imagine a pro-business conservatism in America that would be radically different from today’s pro-investor conservatism. Its emphasis would be not on further enriching rich individuals who invest all over the world, but on helping productive enterprises that hire Americans and produce goods and services in the U.S. Among productive enterprises, a hypothetical pro-business right would focus on firms in capital-intensive, high-technology industries with increasing returns to scale and global markets. These traded-sector industries contribute far more to productivity growth in the national economies in which they are embedded than the financial sector or most service sector industries.

Here are some of the issues on which a possible pro-business conservatism would differ from today’s pro-investor conservatism:

Fair trade. For half a century, industrial enterprises in America have suffered from rivalry with foreign companies or foreign subsidiaries of U.S. multinationals that are backed by foreign governments, particularly in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China. The devastation of American industry by foreign mercantilism need not be of concern to individual investors, as long as they can invest their millions or billions abroad. Nor does it bother multinational companies like Apple, which may be chartered in the U.S. but use production facilities in other countries as export platforms for the American consumer market. In contrast, a pro-business conservatism would call for defending American industries that are targeted for destruction or takeover by foreign governments and their “national champions.” Pro-business conservatives would not call unilateral appeasement of foreign state capitalism “free trade.”

Exchange rates. Nowhere is the conflict of interest between rich global investors and American productive businesses more sharp than on the issue of exchange rates. Many American investors prefer a strong dollar, which helps them buy up foreign companies or other foreign assets. But a strong dollar hurts American companies in the traded sector. A pro-business right would favor a weak dollar that helps American exports or, better yet, a new system of exchange rate stabilization that prevented countries like China from crippling American industries by unilaterally devaluing their currencies.

Public investment. If they existed in the United States, pro-business conservatives like the Rockefeller and McKinley Republicans of yesteryear would agree with President Obama that “you didn’t build that” by yourself. However hostile they were to unions or particular environmental regulations, pro-business conservatives would take it for granted that the American private sector depends on adequate public funding of the public goods of scientific R&D, which spawns new industries and transforms old ones, and state-of-the-art infrastructure, which lowers the cost of doing business. In contrast, investor-focused conservatives since Reagan have sought to slash government R&D budgets to fund further tax cuts for the rich. Today’s right tends to view infrastructure merely as a cash cow to be privatized, so that private shareholders can collect monopoly rents from the public every time somebody in America drives on a highway or pays an electric bill.

Taxation. If there were pro-business conservatives in the United States, lowering income, capital gains and estate taxes on rich individuals would not be a priority for them. Instead, they would favor reducing or eliminating corporate income taxes. Corporate income taxes, which are passed on to individuals anyway, lead companies to minimize their tax payments by means of time-consuming and wasteful international tax arbitrage instead of making goods and services in the U.S. To make up for the lost revenue, a hypothetical pro-business right might favor broad-based, neutral taxes like a value-added tax. And authentic pro-business conservatives might even favor higher taxes on the rich, on the theory — alien to today’s American right — that what is good for rich Americans is not necessarily good for American business.

Inflation. Because they hold so much of their wealth in financial assets that are not adjusted for inflation, the creditor elite in every modern country wants central banks to stamp out all forms of inflation other than asset inflation, no matter the consequences to economic growth or employment. But productive industries can benefit from moderate wage and price inflation, which can encourage investors to invest in productive companies rather than gamble in speculative assets like real estate or commodities. In addition, by burning away consumer debt more quickly, moderate inflation could produce a revival of private consumer spending sooner, to the benefit of productive businesses.

Price stability for energy and commodities. All firms in the important productive traded sector benefit from relative price stability in their inputs — energy and raw materials. It is against the interest of manufacturing enterprises and infrastructure industries like the airline industry to allow individual investors and their agents, like hedge funds, to speculate in industrial commodities like oil. But in recent decades America’s rich, looking for new assets on which they can gamble, have successfully lobbied Congress to dismantle limits on speculation in vital resources.

Decent wages. As individuals, American investors have no particular interest in adequate wages for the majority of Americans. Like Latin American oligarchs, elite Americans who live off global investments can retreat to gated communities in a system of class apartheid. The immiseration of the American people can provide the rentier elite with a buyer’s market in low-wage servants and private security guards. Productive businesses that depend on an American mass market, in contrast, recognize as Henry Ford did that workers are also consumers and that a domestic mass market for goods and services is sustained by adequate wages.

Financial reform. If a pro-business conservatism existed in the United States, as it did in earlier generations, bringing an end to the excessive financialization of the economy that occurred in the last generation would be a priority of the pro-business right, not just the center and left. Pro-business conservatives would denounce the wasteful misallocation of resources to the swollen FIRE sector (finance/insurance/real estate). And they would take it for granted that finance should be the helpful servant of productive industry, not its parasitic master.

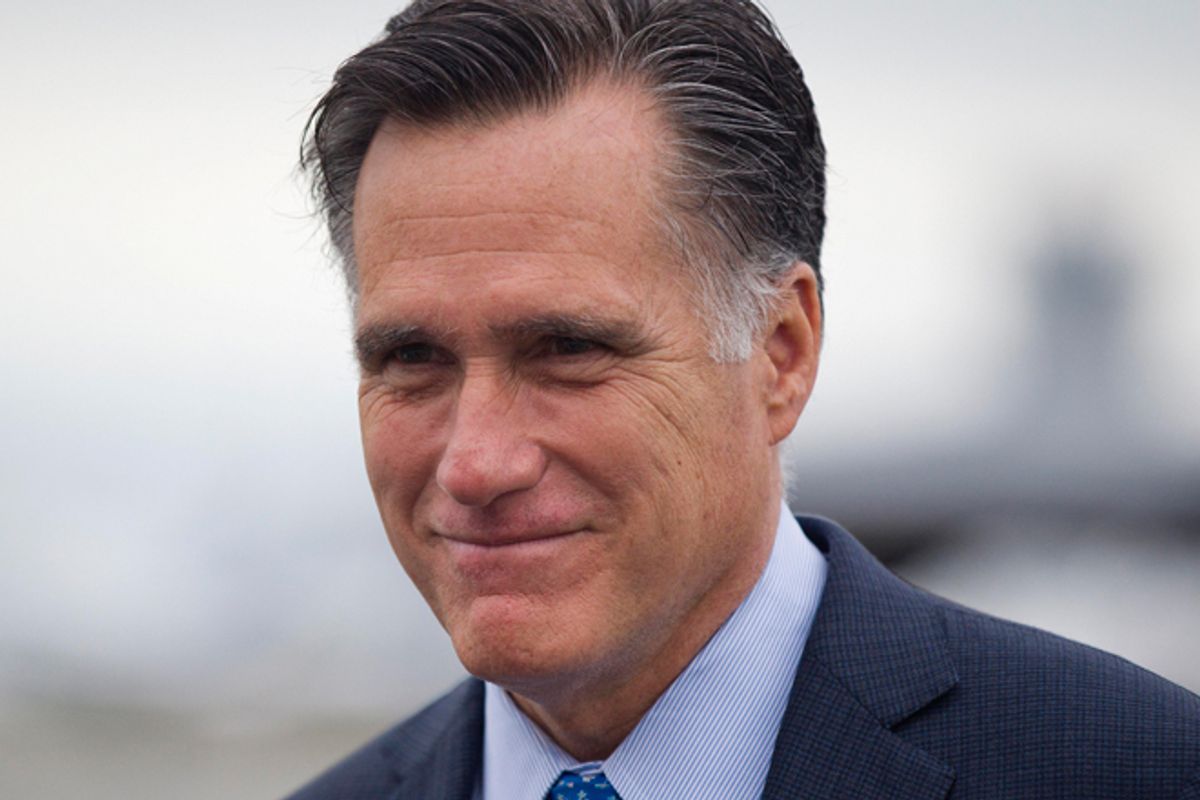

Even if it opposed progressive policies on a number of issues, a conservative movement that put the interests of high-tech, globally competitive industrial enterprises at the center of its agenda would be substantially different from the conservatism of the Club for Growth, George W. Bush, Paul Ryan or Mitt Romney. The chief beneficiaries of today’s conservative economic policies are not the managers, workers and shareholders of productive enterprises inside American borders, but rather rich individuals in general, including trust-fund aristocrats who inherited their unearned wealth from their ancestors.

The absence of a pro-business right in America has created a vacuum that the center and center-left might fill. On issues like the importance of public investment in R&D and infrastructure, the regulation of the out-of-control financial industry, and the need for adequate wages to maintain adequate domestic demand, today’s Democrats tend to be better than today’s Republicans at protecting the legitimate long-term interests of American business.

But pro-business progressivism in the U.S. is hampered by the make-up of the center-left alliance. The natural allies and partners of moderate pro-business conservatives in building a productive economy are industrial labor unions. Organized labor in Japan and Germany has played an important part in the success of those industrial nations. But as America’s industrial workforce has decline in numbers, thanks to hostile corporate and government policy, offshoring and automation, American industrial unions have lost influence.

Most factions to the left of center have priorities other than strengthening America’s industrial base. Some Greens would rather eliminate entire industries from the U.S., like the mining of rare earths, rather than compromise environmental standards. Jeffersonian populists on the left think that bigness in business or banking is inherently evil. Radicals use “corporate” as an epithet and fantasize about building an industrial economy based on socialism or cooperatives. Most important, the powerful neoliberal wing of the Democratic Party, based on Wall Street, has a view of the economy that is practically indistinguishable from that of financial sector conservatives.

Will the pendulum swing back from the financialized economy toward the productive economy? Whether its vehicle turns out to be one party or another, or a new bipartisan consensus, a backlash against the investor-focused, finance-centered economic agenda of post-Reagan conservatives and many neoliberal Democrats in favor of a new agenda promoting productive enterprise within America’s borders is long overdue.

Shares