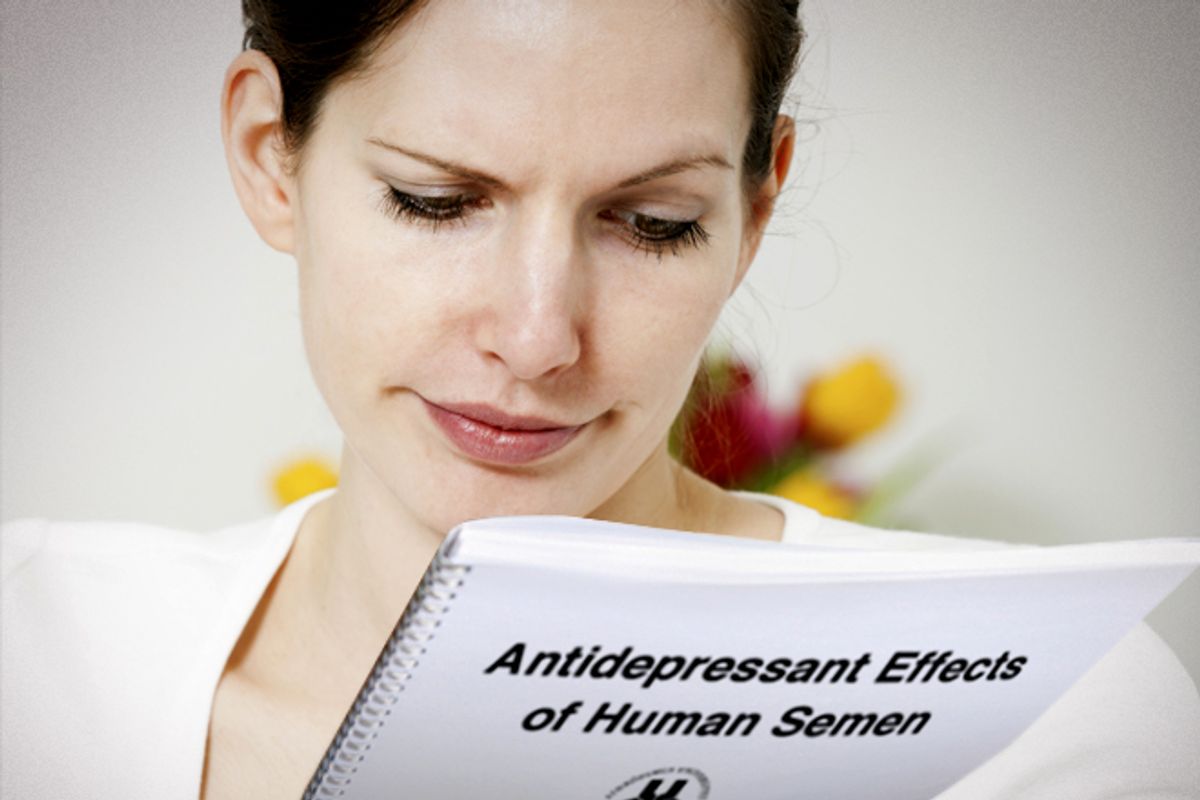

It’s the semen study that won’t stop. In the 10 years since its publication, it has continued to make news – despite being preliminary and involving a measly 293 undergraduate participants. “Every two to three years there will be something about it on the Internet,” says Gordon Gallup Jr., the lead researcher behind the 2002 study. “I don’t know why, other than it’s a very interesting topic.”

Interesting, indeed: Gallup -- who started our phone conversation with, “So you want to talk about semen?” -- found that women who were practicing unprotected heterosexual sex reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms than women who had protected sex or no sex at all. He and his co-authors concluded that semen might act as an antidepressant.

The study just made headlines again this week -- despite being a decade old -- appearing on Gawker, the Huffington Post, the venerable Daily Mail and other online outlets. Just as it has before, it inspired headlines like, “Giving blow jobs makes women happier” and "Oral sex can help women beat depression!" The study made an appearance just last year when the president-elect of the American College of Surgeons controversially riffed in a Valentine's Day editorial about semen's potential mood-boosting qualities and suggested it might be "a better gift for that day than chocolates." (He ... later resigned.)

Clearly, the idea of ejaculate as Prozac is captivating. It could have something to do with the stereotype of women’s hostile relationship toward the stuff. Surely some misogynists see comedic comeuppance in the thought that all those spitters or “not in my mouth-ers” have been depriving themselves of a dose of happy. (Never mind that the study itself has nothing to do with oral sex.) It also certainly fulfills that porn-fantasy of women hungrily, insatiably devouring come (as for why that trope is so pervasive, see here).

Or it could be as simple as Gallup says: It’s just a very interesting idea.

It’s also controversial. When the study first came out some criticized it, speculating that women having condomless sex were more likely to be on birth control, be in a long-term commitment, engage in risk-taking behavior or experience greater sexual pleasure, and that those factors might better explain the results. But Gallup says they either controlled for those influences or the results contradicted them. Others wondered about the negative implications for lesbians.

Speaking of controversial, in a follow-up study, which was published as a graduate dissertation but never in a scientific journal, researchers in Gallup’s lab found evidence of what they termed “semen withdrawal”: women who had unprotected sex in their relationship reported greater sadness post-breakup and tended to have rebound sex more quickly. What’s more, Gallup suggests that postpartum and menopausal depression may relate to semen withdrawal, and that PMS – a period during which many women abstain from sex, he says – “may represent anticipatory semen withdrawal effects.”

Despite his capacity for entertaining seemingly far-fetched hypotheses, Gallup admits that the antidepressant effects of semen “are largely correlational.” As the study itself noted, the "findings raise more questions than they answer." He explains, “We haven’t independently manipulated the presence or absence of semen in the reproduction tracks. In order to conduct a compelling, definitive study that would demonstrate beyond a shadow of a doubt that semen had antidepressant qualities, you would have to directly manipulate the presence or absence of semen -- and that’s obviously problematic for ethical reasons.” That explains why there haven’t been peer-reviewed follow-ups to Gallup’s original study, despite the obvious public interest in the topic.

Amusingly, Gallup says he receives “semen testimonials” from women who come across word of his research online and feel compelled to write him with their own tales of seminal joy.

Even if researchers could reliably prove that semen has an antidepressant effect, he says it’s likely “relatively modest” and certainly “not the way to cure depression.” Although he notes that it's possible Big Pharma could "develop some sort of simulated semen suppository." (You're welcome for introducing that phrase -- and image -- into your brain.)

But the correlational nature of the study -- not to mention its age -- is rarely communicated each time this 10-year-old study is dug up and dusted off.

Shares