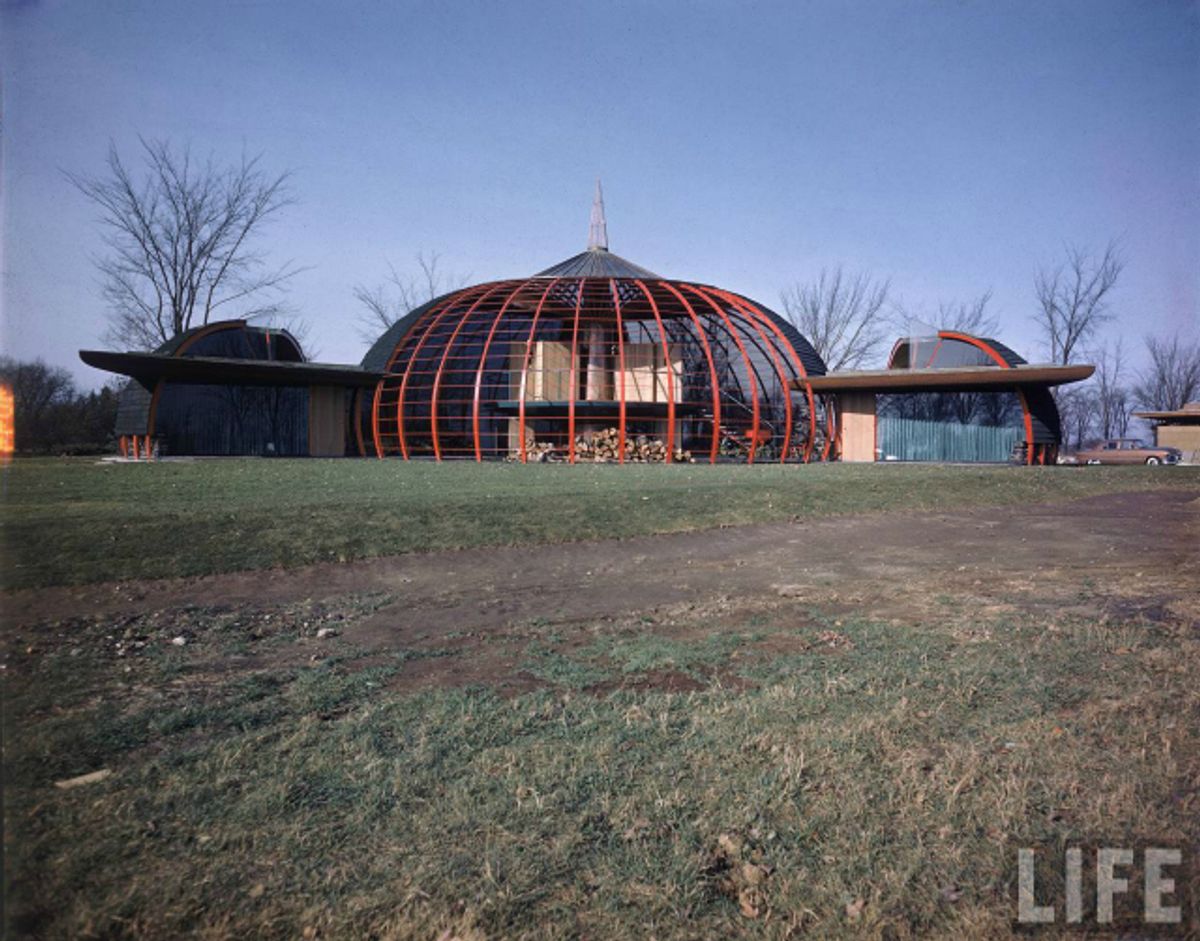

“Architect Bruce Goff, one of the few US architects whom Frank Lloyd Wright considers creative, scorns houses that are ‘boxes with little holes’.” So starts a 1951 Life Magazine article on the Ford House in Aurora, Illinois, one of Goff’s many astounding and imaginative designs that are some of the most structurally forward-thinking of mid-century modern architecture.

Quonset ribs form the Ford House’s birdcage dome, with interior circles looping through with bedroom wings, supported by coal walls decorated with ordinary marbles and an iridescent glass cullet. Cullet is a hardened deposit that forms in glass furnaces and has to be periodically cleaned out. A great innovator who found many ways to elevate found and discarded materials, Goff often used the luminescent cullet and it became something of a signature on his buildings by providing a light accent with an unusual organic texture. When the house for Albert and Ruth Van Sickle Ford was built, it was met with derision by the local community. The unwanted attention of lay architecture critics lead the couple to eventually put up a sign that read: “We don’t like your house either.”

That divisive nature of Goff’s work, coupled with the location of many of his completed design projects — most in rural or residential areas in the Midwest — has limited his work from receiving the recognition it deserves. Goff’s name has faded into the geeky obscurity of architectural reference books and he doesn’t have a centrally located and breathtaking showcase building similar to his friend and mentor Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum to keep him in the public eye — the closest to a Goff landmark is the Pavilion for Japanese Art at the Los Angeles Museum of Art, which was completed in 1988, six years after his death, and is his final work. When the LA structure was unveiled, the New York Times architecture critic, Paul Goldberger, wrote that he hoped that it “will surely bring Goff’s flamboyant architecture to a wider public than has ever seen it before” and added:

“There is a long tradition of highly personal, idiosyncratic, even wild, architecture in Los Angeles; this is one of the only cityscapes in America in which Goff’s expressionistic forms fit right in. In Los Angeles, nothing looks all that bizarre.”

Yet Goff’s bold gestural designs and masterful manipulation of geometric form still inspire, and his influence is particularly felt in the work of advocates for outside-the-box forms like Frank Gehry. Even if much of his best architecture has been lost to exceedingly strange circumstances, including arson, vandalism and deliberate destruction, his other buildings are often in perilous condition and may be lost as well.

Growing up in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, I saw traces of Bruce Goff’s imagination everywhere, from the Redeemer Lutheran Church where I went on Sundays, its walls pocked by blue glass cullet and diamond windows, with massive arrows jutting up from the entrance overhangs as if shot down from a giant’s bow. In the city park is his airy 1963 Playtower, with a spiral staircase leading to an observation sphere (although the door has long been locked due to deterioration). The most astounding, however, was Shin’enKan: ”The House of the Far Away Heart,” an intricately detailed architecture collage of glass mosaics, goose feather ceilings, a white carpet sunken living room, secret passageways, growths of glass cullet, pagoda-like angles and interior and exterior ponds. It was designed in 1956 for Joe Price originally as a bachelor’s pad, then expanded after he married Etsuko Price, and shows how some of the wealthiest people in Oklahoma were taking risks on Goff in a sort of modern architecture patronage, knowing that whatever he created for them would be utterly unique.

Goff lived in Bartlesville after being forced to retire from the University of Oklahoma where he was department chair at the architecture school, which he had invigorated as a center for avant-garde thought on design. The exact reasons for his forced exile are still unclear, but are definitely linked to the fact that he was gay. He was accused of endangering the morals of a minor, although it is fair to say in 1950s Oklahoma, a state which remains highly conservative to this day, that any lifestyle outside the “norms” was likely to cause some hateful prejudice and irrational fear for his young students’ “morals.”

Goff was born in Alton, Kansas, in 1904, although he would mostly grow up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he got his start in architecture, apprenticing at Rush, Endacott & Rush while still a teenager. His first significant contribution was in his early 20s, working on the Prairie School Art Deco wonder that is the Boston Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church. He would never obtain any formal architecture degree, although he would gain experience in the construction battalion of the US Navy during WWII, where he learned to scrape by on unconventional and discarded materials.

In 1947, he was appointed OU’s department chair, where he drove his students to respect their creative impulses, often referencing Gertrude Stein’s idea of the “continuous present,” using it to emphasize the fluidity and flexibility of ideas, introducing masters of classical music along with the ideas of architecture. ”He never told students what to do; he led them back to their own sense of self and let them work it out from within,” wrote former student Philip B. Welch in his 1996 book Goff on Goff: Conversations and Lectures.

Inside Shin’enKan in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Photograph from 1956. (copyright the Art Institute of Chicago)

Inside Shin’enKan in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Photograph from 1956. (copyright the Art Institute of Chicago)Yet the most lamentable loss may be the Bavinger House in Norman, Oklahoma, arguably Goff’s masterpiece, which was destroyed just this past year under very unusual circumstances.

The gravity-defying Bavinger House was designed as a logarithmic spiral of sandstone and glass cullet around a steel pole, with all its rooms suspended by cables above a sitting area with a pond and plants, the same types of plants that grew just outside the walls of the house, blurring the line between interior and exterior. It was designed for Nancy and Eugene Bavinger, both art faculty at OU, and completed in 1955, at which time it was widely celebrated by both popular and architectural publications, even going on to receive the 25-Year-Award from the American Institute of Architects in 1987.

Design for the Bavinger House. (Copyright the Art Institute of Chicago)

Design for the Bavinger House. (Copyright the Art Institute of Chicago)In recent years, the house had suddenly opened for visitors, but that all ended in June of 2011. At first there were reports that a spring storm had damaged the home, bending the spire at a 45 degree angle. However, it soon came out that it was likely Bob Bavinger, the son of Eugene and Nancy, who had himself destroyed the house. A story on This Land Press from November 2011 documents thoroughly the series of shocking events, including when journalists from Oklahoma City’s News 9 showed up and were met with gunfire. Apparently Bavinger had threatened people associated with the OU School of Architecture with its destruction, possibly fearing they would take ownership of it like they had with Shin’enKan in Bartlesville. In the Oklahoma Gazette on June 29, 2011, Bavinger is quoted as saying, in regards to tearing down the house: “It was the only solution that we had. We got backed into a corner.”

A year later, and the strange story continues, as the Bavinger House website has returned after disappearing following last year’s controversy. Apparently a “filmed interview with the son of the Bavinger House” is coming soon, and the news section has some telling unlinked stories such as “the promise made to Eugene Bavinger,” “the past and current political situation,” and “the House will never return under its current political situation.” The last one suggests the home is gone, but still exists somehow in pieces, dismantled as many suspected, although it would be impossible to rebuild it exactly how it was, and likely outside the resources of the current owner.

The only time I saw the Bavinger House, I got a strange sense of unease. It was in December 2010, and I remember me and my brother driving down a narrow rural road through a woods, past several identical old cars lined up under the trees, with other junk and and old house appearing like any hard-on-its-times off-road Oklahoma home. A man approached our car, but we didn’t get out, there was something odd about the place, although I snapped one photo from the window. I do regret not venturing inside to see its curious organic interior, but I was also not completely surprised to hear of its unfortunate and unusual fate.

Thankfully, there are still many buildings by Goff that can be saved, although their deterioration would require some serious funding and concentrated preservation efforts. One of these is theHopewell Baptist Church in Edmond, Oklahoma, designed to reference a teepee and built by volunteer members of the congregation after Goff’s design using discarded oil field pipes. (Goff’s buildings, including the Bavinger House, were often built by the hands of their owners under Goff’s direction.) This past winter while I was visiting Oklahoma City, I decided to finally see it. It happened that the pastor of the church was there while I was taking photos and was incredibly generous in allowing me to see the interior and also describe how it was in its original glory (these photos on PrairieMod from 1959 show how dilapidated it has become, due to a roof leak that is beyond the financial resources of the congregation to fix).

Dome of Hopewell Baptist Church (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Dome of Hopewell Baptist Church (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The church was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. Looking at the broken floors and open ceiling, it obviously needs a lot of work, yet even in that state it is awe-inspiring. The oculus at the peak of the dome warmly illuminates the room, a perfect example of how light was as much a material for Goff as anything physical. It must have been very impressive to be under the soaring dome when it was in better shape, and hopefully it can get the funding it needs before it goes too far beyond repair.

Even as I’ve moved out of Oklahoma, Goff and his work continue to linger in my mind, and I long for some of his whimsical experimentation in the sterile, uniform buildings that crowd the country’s cities and towns. Goff recognized that the spaces people inhabit can be challenging and still livable, that four walls don’t always have to make a room, that a room doesn’t necessarily need walls at all.

When I was visiting a friend in Chicago, we were walking in the historic Graceland Cemetery, when I saw a gleam of aquamarine glass on a small headstone, the same glass I immediately recognized from Goff, a glass that is simultaneously beautiful and broken, both smooth and sharp, and like his work never exactly the same. But why would he be buried in Chicago? He wasn’t even on the cemetery map, losing out in the architects category to Louis Sullivan and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. I later learned the glass was salvaged from the scorched remains of Shin’enKan, and Goff’s own ashes were only finally buried in 2000, nearly 20 years after his death. He had no immediate family, his estate going to Joe Price, and a burial just never happened. He was finally interred through the efforts of a former apprentice, Wayne Gustafson, who selected Chicago as the hub of Midwestern architecture and the site of some of Goff’s significant works. Gustafson designed the tombstone that perfectly reflects Goff’s aesthetic.

The fact that the destruction of the Bavinger House didn’t make national news — even local news appear to have jettisoned the fact down the endless hole of the 24 hour newscycle — and that his standing structures continue to rot, does not bode well for the future of Goff’s work. However, the rural and residential nature of much of his architecture may be a blessing in disguise, as there are still many people living in his homes who love and care for the unique places. Beyond the physical remnants of his singular career, I also hope that current and future architecture students will stumble upon his organic modern architecture and be intrigued or inspired by the odd buildings that look like they may have landed in the red dirt of Oklahoma thinking it was Mars.

Shares