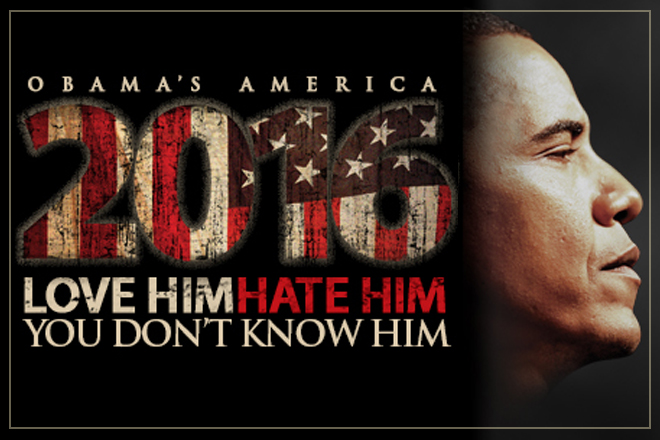

Somebody in Dinesh D’Souza’s shaggy, piecemeal right-wing screed “2016: Obama’s America” definitely has a problem with post-colonial theory and the conflicted ideologies of third-world intellectuals. But I don’t think it’s Barack Obama. A blend of genuinely fascinating observations and shrill, repetitious character assassination, “2016” is the surprise hit documentary of late summer, hypothetically lifting the spirits of true-hearted Americans as they battle to thwart the dastardly schemes of … well, the middle-of-the-road, drone-happy politician who has occupied the White House for the last four years, apparently without showing his true colors.

As far as actual argumentation about Obama goes, there’s nothing new here that Sarah Palin didn’t try in 2008: The president spent his childhood and young manhood pallin’ around with terrorists of various stripes and haunted by the specter of his Kenyan radical dad, and those influences have shaped him into a creature of unique deviousness. While the birthers may not be precisely correct when it comes to troublesome factual details – D’Souza does not endorse, disavow or even mention the kookier conspiracy theories – they’re right at the level of essence and insight. Obama is a dyed-in-the-wool anti-American who was born in a hospital with a funny name, reared on his absent father’s “Third World collectivism” and elected president in a nationwide racial pity party after concealing crucial elements of his own background. He is “weirdly sympathetic to Muslim jihadis” and hopes to enable a “United States of Islam” in the Middle East while raising taxes to 100 percent at home. Any questions?

But none of the fragments of innuendo flung at the screen in “2016” – did you know that Barack Obama Sr. met Stanley Anne Dunham in Russian class? — is one-third as interesting as the story of D’Souza himself, the Indian-born conservative intellectual who co-wrote and co-directed this film, which is based on his 2010 book “The Roots of Obama’s Rage.” As the film’s narrator, interviewer and star, D’Souza is an awkward, nebbishy, halfway appealing figure with bad glasses and ultra-square button-down shirts, uneasily reading from a notepad. (Despite this film’s unexpected success, he should probably stick with the day job.) One could and perhaps should use scare quotes around “intellectual” when it comes to someone who would crank out a piece of campaign-season partisan hackwork this crude and sloppy. (By this standard, James Carville looks like Immanuel Kant.) But I’ll submit that D’Souza is clearly an intelligent man and that some of his work meets the definition, and leave it at that.

Since D’Souza engages in free-range amateur psychoanalysis of the president, darkly but vaguely claiming that Obama holds “an ideology remote from what Americans believe in or care about … something completely separated from American thought altogether,” I feel emboldened to respond in kind. As D’Souza is (I believe) painfully aware, that ominous phraseology describes him as much as or more than it describes Obama, and “2016” is more a work of tormented autobiography than biography. It isn’t even especially covert, since the first third of the film features odd, half-dramatized vignettes drawn from D’Souza’s own life: a little boy in Mumbai, reading a textbook about the greatness of America; a Dartmouth undergrad with his conservative cohorts, being dressed down by a liberal dean for publishing satirical takedowns of Jimmy Carter.

Some of this autobiography is meant to establish D’Souza’s generational consonance with Obama, and thereby, I guess, his ability to understand him: They were both born in 1961, graduated from Ivy League schools in 1983, and got married in 1992. D’Souza skates nervously past the fact that he and Obama both have highly unusual and, one might say, globalized backgrounds, even though it’s obviously a source of his fascination with the president. Obama was, of course, the biracial product of an international marriage, born in Hawaii and largely raised in Indonesia before moving on to prep school and an elite higher education. D’Souza was born into the tiny Roman Catholic minority in India, and came to the United States on a Rotary International scholarship as a teenager, attending high school in Arizona before going to Dartmouth.

Both of these talented young men, I think it’s fair to say, succeeded on their merits, and also because American society and its institutions in the 1980s were abruptly opening up to people of color, especially when they seemed to reject or defy the racial stereotypes and racial grievances of the past. D’Souza quotes passages from Obama’s memoir “Dreams From My Father” in which the future president wryly discusses his discovery that whites often seemed grateful to meet a black man who was courteous and not visibly full of rage. Indeed, Obama has made clear on several occasions that he understands his 2008 campaign, like his election as president of the Harvard Law Review, depended partly on his racial ambiguity and on people’s tendency to project their own meanings onto his calm, reserved demeanor.

With his vested interest in denying the persistence of racism in American life, D’Souza seems unwilling to address the ways that his own racial and national background have made him useful to the right. Would he have been hired as a Reagan White House aide at age 27, and gone on to a stellar and lavishly remunerated career with right-wing think tanks, publishing houses and academic institutions, if he had been a young conservative from Indiana rather than India?

Indeed, D’Souza’s entire career is based on being a man from the developing world who resists the left-wing dogmas of anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism so common in the intellectual circles of those countries, and who has instead embraced a cartoon version of Americanism. Being born an Indian Catholic was evidently not weird enough; in his American life D’Souza has reinvented himself as an evangelical Christian, and authored apologetic tomes about the nature of God and the prospects of the afterlife. Neither was it sufficient to become a Reaganite in favor of hawkish policies abroad and trickle-down economics at home; D’Souza had to become the kind of William Bennett-on-steroids nutjob who argues that the cultural left in America was responsible for the 9/11 attacks, and that gay marriage can’t work because women are the only force that can civilize men. In a disarming if ill-considered moment, he once told Stephen Colbert that he shared Islamic militants’ hostile view of liberal American decadence.

Even some of D’Souza’s fellow travelers on the right think that his campaign to unmask Obama as a Manchurian candidate preloaded with a Frantz Fanon-style software program aimed at destroying America is a bit unhinged. Daniel Larison of the American Conservative described the September 2010 Forbes article that sparked D’Souza’s book as perhaps “the most ridiculous piece of Obama analysis yet written,” which is certainly saying something. I genuinely think we need to go deeper, and look for a psychological explanation, an upside-down version of the one D’Souza applies to Obama.

My own hypothesis is that D’Souza looks at the cosmopolitan politician with the third-world upbringing and sees a distorted mirror reflection, as well as a road not taken. There is no question that the young Obama flirted with Marxism, black radicalism and anti-colonial ideologies during his years at Occidental College, Columbia and Harvard Law. He has discussed the allure of those philosophies, with the dispassion that seems to be his natural instrument, in his autobiographical works. No doubt those associations, on their own, are enough to scare some voters off, but D’Souza simply cannot believe that the young Obama could have studied with professors like the late Palestinian renaissance man Edward Said or brainiac Brazilian philosopher Roberto Mangabeira Unger (both of whom are rendered here as unrecognizable caricatures) without becoming perverted to their supposedly sinister agenda.

D’Souza’s demented anti-Obama crusade feels personal more than political. Early in “2016” he says that his own grandfather was an Indian nationalist driven by anti-British and anti-white prejudice, who urged him not to go to America. This is a man who is intimately familiar with the seductive pull of anti-colonial thinking – the tendency to blame the legacy of Western domination for all the developing world’s problems – and must struggle manfully against it every hour of every day. He’s cast himself as a Brooks Brothers version of Frodo Baggins in an epic psychodrama no one else understands, fighting on behalf of a culture he largely despises against the power of the One Ring of post-colonial theory, forged in secret Ivy League seminar rooms by Barack Sauron Obama. On the famous theory expressed in David Mamet’s play “Edmond” that every fear hides a wish, I wonder which of these guys really dreams about destroying America.