It’s proverbial that, in college football’s Southeastern Conference, “if you ain’t cheatin’, you ain’t tryin.’” (Given that SEC teams have won the last six national championships, it’s fair to speculate that there’s been a whole lot of tryin’ going on.)

Suitably translated into Latin, this might as well be our new national motto. In America today, crime pays, at least if you’re high up enough in the social hierarchy to take advantage of the fact that we’re increasingly willing to accept that laws are for little people.

What’s happened in the worlds of high finance and high politics can be analogized to what allegedly happened in the world of competitive cycling during the Lance Armstrong era. According to Armstrong’s former teammate and later rival Tyler Hamilton, all the top riders, including Armstrong and Hamilton, were using banned performance-enhancing drugs when Armstrong was winning seven Tour de France races.

According to Hamilton, they were doing so for two reasons: It was impossible to compete at the highest levels without cheating, and because the enforcement regime to catch cheaters was so easy to elude (Armstrong, who continues to deny using PEDs, points out that he has passed hundreds of drug tests).

What Hamilton describes, in other words, is not so much a series of individual cases of rule-breaking, but rather a culture of systemic corruption. This is a useful way to think about the government’s recent decisions not to bring any charges in a couple of high-profile cases, involving far more serious matters than bicycle races.

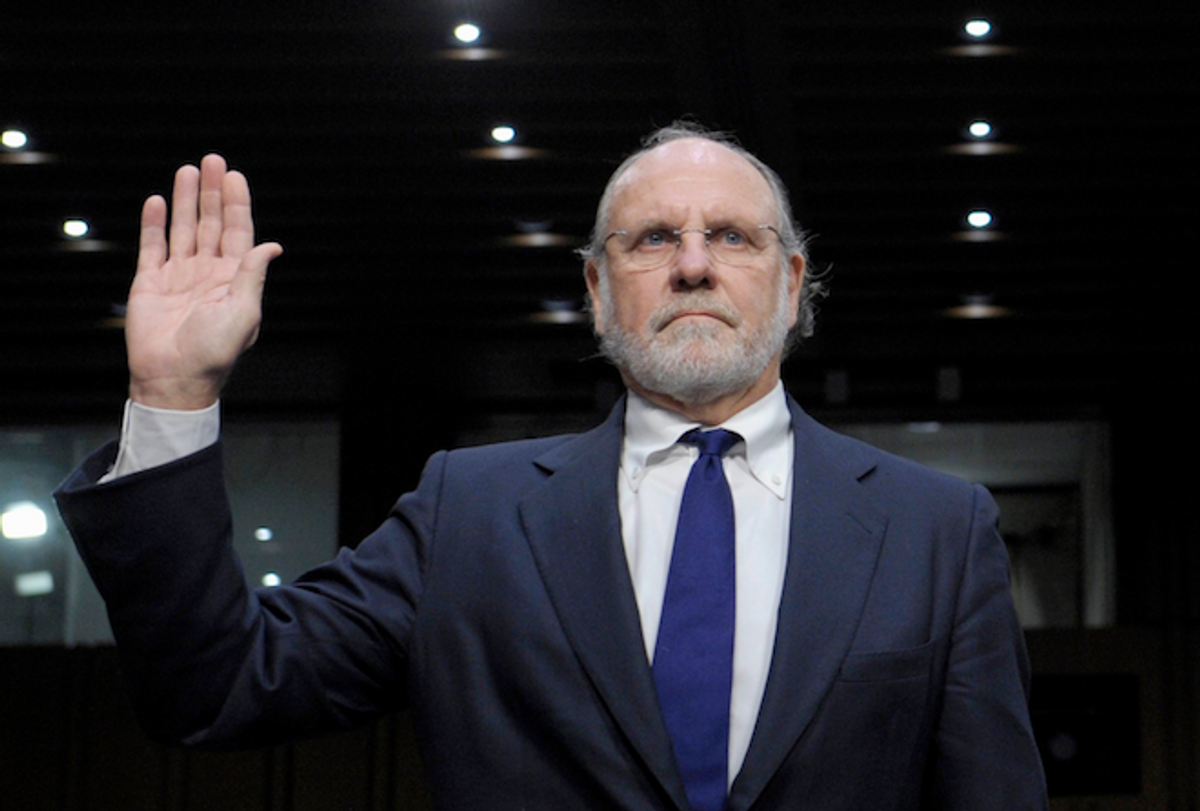

The first case involves the collapse of the derivatives broker MF Global, which was led by former New Jersey Gov. Jon Corzine. The MF Global scandal appears to involve the – to put it as delicately as possible – “misappropriation” of $1.6 billion, which the company’s top executives wrongfully took from customer accounts, in an ultimately failed attempt to meet its outstanding obligations and avoid bankruptcy.

After absorbing a ferocious legal and public relations assault from the company’s hired guns, federal prosecutors have apparently decided that “chaos and porous risk controls at the firm, rather than fraud, allowed the money to disappear.” This can be called the “it’s complicated” defense, which Wall Street masters of the universe have been deploying with great success ever since they wrecked the world economy back in 2007.

As brazen as this defense is in general, in the case of MF Global it doesn’t come close to passing what lawyers call the red-face test:

But MF Global is different. This is not complicated at all. This is just stealing. You owe money, you don’t have the cash to cover it, and so you take money belonging to someone else to cover your debts. There’s no room at all here for an argument that this money was just lost due to a bad investment, an erroneous calculation based on someone's poor understanding of a complex transaction, etc. It’s straight-up embezzlement.

But if you hire enough $800-an-hour litigators, and engage Don Draper to make sure the word “chaos” appears in every story about your clients’ unfortunate tendency to misplace more than a billion dollars of customer money at a time suspiciously convenient for the client, then suddenly what looks to the uninitiated like a straightforward case of theft becomes ... complicated.

Another thing that can become surprisingly complicated is the proposition that torturing people to death is a crime. Last week Attorney General Eric Holder announced that no charges would be brought against U.S. government officials involved in two particularly infamous cases, where “enhanced interrogation techniques” were used that went beyond the “techniques” authorized by Bush administration lawyers.

In other words, representatives of the American government who tortured people to death, using methods of torture more brutal than the kinds of torture authorized by the government, aren’t going to be prosecuted because, according to the Obama administration, it’s important “to look forward instead of backward.”

All this represents an institutionalized culture of corruption. The rationale underlying the unwillingness to prosecute rich and powerful people for stealing large amounts of money or ordering prisoners to be tortured to death is similar to that which, according to Hamilton, underlie the comparatively trivial rule breaking he purports to document: If “everybody” – meaning everybody well connected enough to get away with breaking the rules – is crooked, then in a twisted sense, nobody is.

Shares