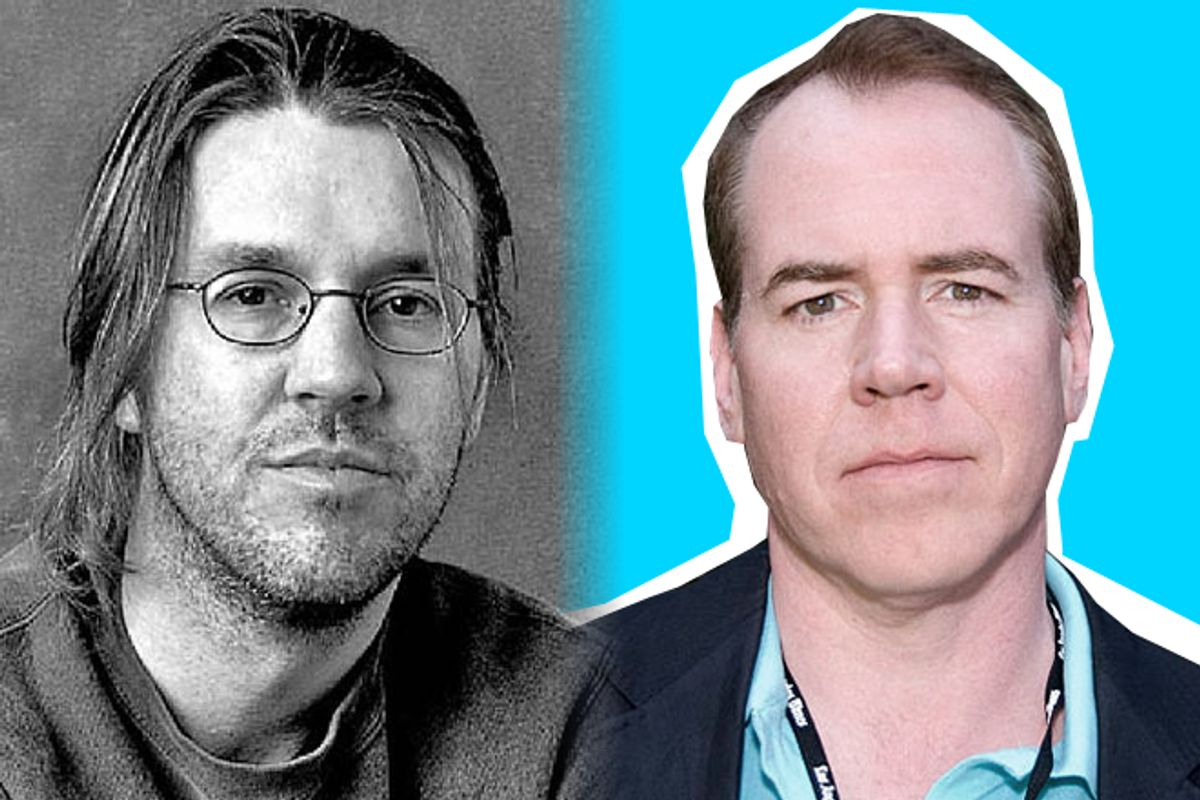

As much of the literary world knows by now, Bret Easton Ellis went off big time against David Foster Wallace the other day on Twitter, driven into a serial, sputtering rage by his reading of D.T. Max’s newly published biography of Wallace, "Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story." Some would say that Ellis is being exceptionally hostile and ungenerous toward a tragically tormented writer who, having hanged himself, is in no position to defend himself. Me, I chalk it up to Bret being Bret and am not inclined to be judgmental. But then, I am in the unique position of having published both of these phenomenally talented and radically antithetical writers just as they were starting out, and I think I know some things that underlie Bret Easton Ellis’ volcanic pique.

I was a young(ish) editor at Penguin Books in 1985 when I was given the galleys of "Less Than Zero" to read by Simon and Schuster for reprint consideration. I had already seen Bret Ellis on a PEN panel about the influence of the '60s on contemporary fiction and had been greatly taken by his dry deadpan wit, such a refreshing contrast to the damp lefty pieties usually tossed around at such conclaves. I loved "Less Than Zero." Just loved it. I picked up echoes of Didion and Antonioni and Nathanael West and basically thought it was an unnerving achievement in California neo-nihilism and a harbinger of something very scary growing in the culture at that time. We took a paperback floor, the book became a sensation and a bestseller in hardcover, and we eventually paid $99,000 for the rights at auction -- at that time an impressive sum for a first novel. A year later we published the paperback in our Contemporary American Fiction series and it too became a bestseller. Meanwhile Bret had been lumped together by the literary press with Jay McInerney and Tama Janowitz as a literary Brat Pack who found their subject matter in the young and wasted making the druggy rounds of night life on either coast. Which was not entirely wrong, but which elided the real differences among these three writers -- and set them up for a really nasty backlash.

In 1986, just after we published the paperback of "Less Than Zero," the manuscript of David Foster Wallace’s first novel, "The Broom of the System," hit my desk. (That’s what manuscripts used to do, hit desks, not email in-boxes.) And I loved it too. Just loved it. But for very different reasons, of course. Here at the high tide of American minimalism, and in distinct contrast to the louche novels of Ellis and McInerney and Janowitz, was a big, brainy throwback to the imperial novels of the Great White Postmodernists -- Barth and Coover and Gaddis and DeLillo and especially Pynchon, all writers I had cut my literary teeth on. Well, well, what have we here, I thought. So I signed the book up, did my best to edit it (you can read about the futility of that enterprise in Max’s biography), and we published it as a trade paperback original in the Contemporary American Fiction series. The reviews were pretty much all one could desire for a first novel, and a number of them drew a sharp distinction between Wallace’s hyperintelligent and maximalist approach and the work of the Brat Packers, who were already being set up for a critical flogging. Bret Ellis being one of those writers on whom nothing is lost, these invidious comparisons would not have escaped his attention. The anschluss arrived with the publication of his underrated second novel, "The Rules of Attraction," which we would also reprint at Penguin despite a cascade of disapprobration. Not pretty and really not fair.

In late 1988 I moved from Penguin to W. W. Norton, taking with me David’s second book, the collection "Girl With Curious Hair," which Penguin had refused to publish for legal reasons. (Long story.) The title story, about a bunch of L.A. punks misbehaving at a Keith Jarrett concert, struck me as an obvious and expert parody of Bret Ellis’ affectless tone and subject matter and I said so. David, ever disingenuous about his influences (you could barely get him to admit he’d even read Pynchon), denied ever having read a word of Bret’s work – an obvious lie that I let pass. I am certain, though, that Bret took peeved notice when the book was published.

So there it was: two hot (sorry) young writers of about the same age, wildly different in style and temperament, inhabiting the same crowded literary space and clearly getting on each other’s nerves. I know that David envied the savvy with which Bret Ellis and his peer group handled the challenges of a literary career – and castigated himself for that envy. Both fought hard and successful battles against alcoholism and substance abuse. (I watched both men at different times pound back multiple drinks in startlingly short order and each time thought, Uh-oh.) Both went on to publish culture-shaking novels. "American Psycho," a macabre put-on that amplified every cliché about yuppie scum to Grand Guignol volume, created a firestorm when the literal minded (of whom there are so many) failed to get the joke. "Infinite Jest" transformed private torment into a vast metafictional diagnosis of our entertainment-bedizened cultural condition, and, weirdly, sounded the first notes of a quest for an irony-free sincerity that has become a ruling style of David’s generation and the ones that followed.

At the moment, the Wallace style is dominant and that is what drives Bret Ellis nuts. David’s 2005 commencement speech to the graduating class of Kenyon College, “This is Water,” has assumed the stature of a manifesto and ultimate statement. But, soul-pocked baby boomer that I am, I don’t buy it as a guide for right behavior. It feels uncomfortably close to those books of affirmations, no doubt inspiring but of questionable use when the hard stuff arrives. I truly believe that David was the finest writer of his generation, but his design for living seems to me naive and likely to collapse at the first impact of life’s implacable difficulties. It badly needed an injection of Montaigne or Marcus Aurelius.

Me, I find Bret Ellis’ scalding, cynical, brittle, savagely unillusioned worldview curiously refreshing. He is the Loki or Trickster of the literary world (or maybe the Lou Reed), poking sharp sticks in our eyes and daring us to figure out if he could possibly mean that. Deal with it. In a culture that has the phrase “Good job!” on endless rotation, he dares to say, over and over, “You must be fucking kidding me.” He’s incorrigible, he’s not a nice boy, he doesn’t care if you become a better person, he is not in any way seeking your approval. Good for him. Some brave college should ask him to do a commencement address.

Anyway, I count myself ridiculously lucky to have been in on the beginnings of these two striking literary careers. Two oddly twinned stories that apparently still have some twists left in them yet.

Shares