Last year Jonathan Kay, a Canadian journalist, published “Among the Truthers,” an interesting chronicle of, among other things, post-9/11 conspiracy theories. Many of these theories are outlandish on their face, such as claims that the twin towers were brought down by controlled demolition, that airplanes never struck them, that Flight 93 landed in Cleveland rather than crashing in a Pennsylvania field, and so forth.

Now if I were inclined toward a conspiratorial view of the world, I would speculate that the very outlandishness of these claims is itself part of a conspiracy to obscure what really happened on 9/11. This meta-conspiracy theory would go something like this: Over the past 11 years, it has slowly but inexorably become clear that the CIA uncovered key details of the 9/11 plot several months in advance, and tried on numerous occasions to get the Bush administration to take action to stop it.

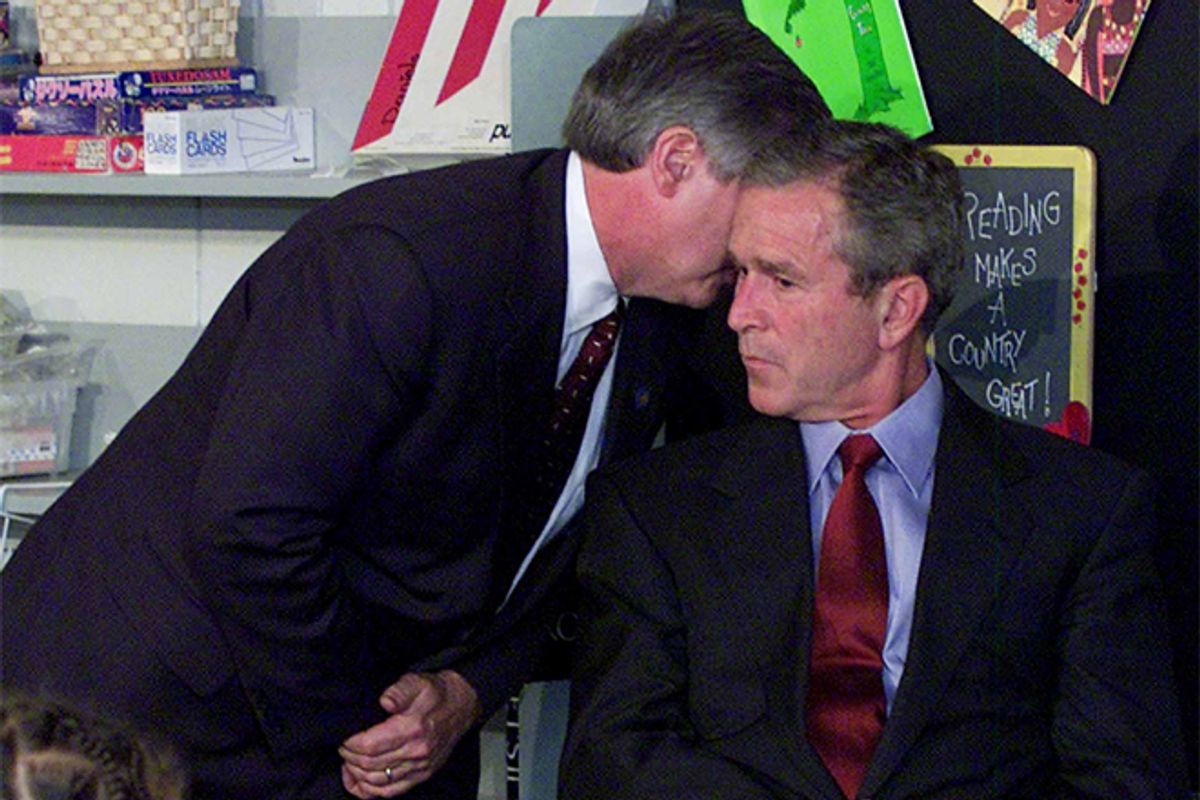

In a New York Times Op-Ed, Kurt Eichenwald offers new evidence on this front. Throughout the spring and summer of 2001, Eichenwald claims the CIA presented the administration with compelling evidence that al-Qaida operatives were in the United States, that they were planning a major terrorist attack intended to produce mass casualties, and that this attack was imminent. In response, the Bush administration did nothing.

Indeed, the administration’s level of inaction was so negligent that senior intelligence officials actually considered resigning, so as not to be in a position of responsibility when the attack took place:

Officials at the Counterterrorism Center of the C.I.A. grew apoplectic. On July 9, at a meeting of the counterterrorism group, one official suggested that the staff put in for a transfer so that somebody else would be responsible when the attack took place, two people who were there told me in interviews. The suggestion was batted down, they said, because there would be no time to train anyone else.

For a long time, the administration successfully covered up this series of events, by employing the clever strategy of revealing a small and ultimately misleading part of the truth: In April 2004, it declassified a single daily briefing, that featured the startling headline “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.,” but on closer examination did not contain much in the way of specifics regarding the attack, which took place just 35 days after the memo’s printing.

Releasing this single briefing was deeply misleading, because it gave the impression that the administration had been given just one rather vague warning about the impending attack, rather than a series of much more concrete briefings, which ought to have put the government on high alert. The shocking truth, if Eichenwald is correct, is that the Bush administration was told enough in advance about the nature and timing of the 9/11 attacks that it could quite possibly have stopped them, but, for whatever reason, President Bush and his advisers chose to ignore those warnings. (According to Eichenwald, some White House neocons believed, “Bin Laden was merely pretending to be planning an attack to distract the administration from Saddam Hussein, whom the neoconservatives saw as a greater threat.”)

Note that to this point my meta-conspiracy narrative has the unusual virtue of being based on nothing but what are now the known facts of the matter. To go beyond this, we have to enter the realm of speculation, which is where things get “conspiratorial” in the dismissive sense of the word. We might, for example, speculate that certain neoconservatives in and around the White House were not wholly displeased with the failure to stop the attacks, since they provided an emotionally compelling, although completely irrational, basis for launching the invasion of Iraq these people were laboring to bring about.

We could take one more step, and note that, in the years after the attacks, neoconservatives played an active role in both publicizing and debunking the most extravagant 9/11 conspiracy theories, because nothing is more useful to a real conspiracy than directing attention to a series of absurd ones, which tend to discredit the very concept itself. (Note how former Bush press secretary Ari Fleischer is already attacking Eichenwald as a “truther.”)

Now, do I believe in this meta-conspiracy theory? Of course not, because I am – or at least aspire to be – a Very Serious Person, and Very Serious People do not believe in conspiracies. They do, however, participate in them.

Shares