"'The Wire' is like a Victorian novel" -- this facile, cocktail-party insight has been cropping up a lot lately, although it's hard to see why someone who truly loves both the HBO series about life and crime in contemporary Baltimore and the fiction of 19th-century England would insist upon it. The latest and most elaborate manifestation of this notion is "Down in the Hole: The unWired World of H.B. Ogden," a book based on a blog post that posed (unconvincingly) as a scholarly paper. The tongue-in-cheek treatise champions an almost-forgotten serialized novel by the (fictional) Ogden, author of a purported "Victorian masterpiece," titled "The Wire," which shares many elements with the HBO series. The new book offers (equally unconvincing) excerpts from the imaginary serialized novel, as well.

The original blog post by Sean Michael Robinson and Joy DeLyria was an inventive, larkish effort to liken the revered TV show to a popular art form from 150 years ago, one that has since attained the status of literature. Point taken! The entertainment of today can indeed become the art of tomorrow. And, by now: point belabored. It makes sense that a series like "The Wire" will be regarded as a "serious" cultural artifact by future generations; it's regarded that way right now in many quarters, after all. But whatever its prestige trajectory is likely to be, "The Wire" is not, in fact, much like a Victorian novel.

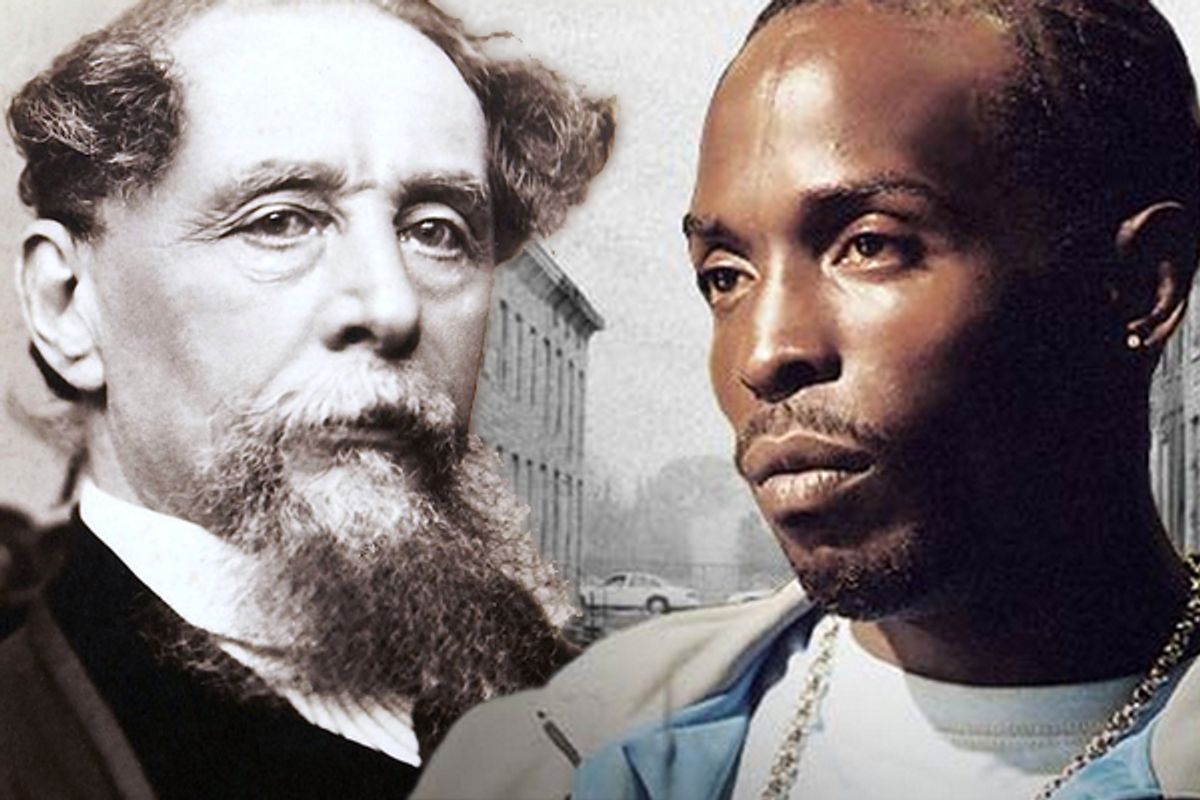

The universally cited comparison here is the work of Charles Dickens. I suspect that's because Dickens is the only Victorian novelist some of the comparison-makers have read -- assuming that their knowledge isn't exclusively based on four-part BBC dramatizations. Dickens was the most popular of the Victorian novelists, then and now, but not, of course, the only one, and his work is not representative of his entire cohort. The Victorians wrote all kinds of novels. Even Dickens wrote more than one kind.

"The Wire" has three things in common with the average Dickens novel: It's long, it was produced and initially presented in serial installments, and it uses narrative to call attention to social problems. That's about it, and it's not all that much. How does "The Wire" differ from Victorian novels? Let us count the many, many ways.

Perhaps the most obvious difference: "The Wire" is a dramatic work, not a prose narrative. This distinction is not trivial. It profoundly shapes what each work can do and how it can do it. Like all dramas, and unlike most novels, "The Wire" can offer us no access to the interior lives of its characters apart from what we construe from their actions. "My mother and I had always lived by ourselves in the happiest state imaginable, and lived so then, and always meant to live so," David Copperfield announces. Picture the work a filmed narrative would have to do to convey this thought -- not just how two people feel about their lives now, but how they anticipate their future -- compared to the ease with which Dickens is able to get it across in just a fragment of a sentence. And Dickens doesn't even specialize in characters with complex inner lives.

On the other hand, a drama -- particularly a filmed one -- can dispense with all descriptions of scenery, people and action; because it can show, it need not tell. Victorian novels, for the most part written before the prevalence of photography, are stuffed with descriptions of people and places. The culture didn't have as many pictures, so they used thousands and thousands of words. (The great brio and vividness of Dickens' descriptions are hallmarks of his genius, the thing that makes Dickens Dickens.)

A drama, by contrast, has the bodies, voices and performances of its actors, and the spectacle of its setting, all of which can communicate the physical world of the story with much greater economy. Different parameters call for fundamentally different forms of storytelling. Although "The Wire" (each season in itself, and the series as a whole) is indeed long (like a novel), with a complex plot, the tools it uses are still those of plays, film and other dramatic media. Yet for some reason you seldom hear it compared to, say, Shakespeare.

Many Victorian novels began as serials published in regular installments in magazines, frequently penned by authors racing against the clock. True, TV series also appear in installments produced under acute time pressure. But any similarities rooted in the serial structure are dwarfed by the fact that television dramas, unlike novels, are the product of collaboration.

In series television, not only do multiple writers contribute and revise scripts and assorted directors shoot the episodes, but the actors themselves contribute to and affect the unfolding of the story. Their performances influence the writers, inspiring them to come up with more funny scenes, or sad ones, or simply greater emphasis on characters who emerge as especially captivating. The authors of 19th-century serial novels would sometimes improvise their stories as they went along, tweaking them this way or that in response to public enthusiasm or censure, but their novels didn't actually consist of the creative contributions of many other people. No TV series is a single person's vision the way a novel is.

As Robinson acknowledged in an interview for the Atlantic's website, Victorian novels "sometimes highlighted a single protagonist with a single through-line (think 'David Copperfield'), but even these featured large casts, multiple plotlines, and sprawling narrative focused on many different aspects of life." That's not quite true. Victorian novels almost always center around a single protagonist (or a small group, such as a couple or family). This is characteristic of the novel in general, even if 20th-century works would later experiment with that convention. Some 19th-century novels, those in the Romantic tradition, focus on a single psyche's conflict with the world ("Jane Eyre"), but even the ones that employ the much-invoked "broad social canvas" -- those by writers like William Thackerey, George Eliot or George Meredith, for example -- organize their books around the fortunes of one or two figures.

This is how a novel encourages its reader's engagement with "people" who consist of little more than black marks on paper. Prose has no face, no voice, no breathing presence to persuade its readers to believe in the humanity of a fictional character. It uses the centrality of the main character to finesse our sympathy by means of identification: We all think of ourselves as the heroes or heroines in the stories of our own lives.

Much of the process of "getting into" a novel involves fastening our interest onto the fate of that main character. Creating that investment can take a while. It requires imaginative work on the part of the reader, on whose indulgence it is unwise to presume. Victorian novels may have a lot of supporting characters -- and Dickens specialized in them -- but very, very few of them are true ensemble pieces in which the interest is distributed equitably over many figures and story lines.

Ensemble pieces can be hard to pull off even in the least concise dramatic forms, like series television. But to secure its viewers' interest and investment in the story, a dramatic ensemble has the added advantage of its actors. You don't have to seduce the viewer into believing in the humanity of people they can literally see and hear. Gifted actors can impart a great deal about a character in a single expression or gesture, but they also supply the less tangible allure of their own personal charisma, whether it's the physical majesty of Idris Elba's Stringer Bell or the winsome scruffiness of Andre Royo's Bubbles. Possibly the most annoying thing about the "The Wire"-as-Dickens truism is that it elides the contribution of the series' actors.

In the Atlantic interview, Robinson says, "If we're treating prose style and narrative deftness in a novel as analogues to visual style or other formal elements of television storytelling, I don't think 'The Wire' really stands up aesthetically to most of Dickens' work." But much of the social texture and energy Dickens conveyed with his prose style is accomplished in "The Wire" by the acting, not the cinematography or direction. Not only is "The Wire" not a novel, it's also not a movie. Feature films are primarily a visual medium driven by the director. However, serialized television, though also visual, is driven by writers and actors who (in the best cases) collaborate dynamically.

"The Wire" does resemble Dickens' fiction in that both were created by and for bourgeois audiences seeking representations of underclass life, although Dickens, unlike the makers of "The Wire," also had a significant working-class following. Despite appearing in a medium associated with popular entertainment, "The Wire" has never been widely watched or discussed outside certain rarefied circles, so it doesn't even replicate the historical or social position of Dickens' novels. You can't say that "The Wire," although a mere popular entertainment by today's standards, will someday, like Dickens' fiction, graduate to the status of a classic. "The Wire" is not especially popular, and certainly not as popular as Dickens once was. This limited appeal has a lot to do with the worldview of "The Wire," which is, again, totally not like Dickens'.

Dickens was a sentimental novelist, whose depictions of squalor and hardship -- what most people mean when they say "Dickensian" -- come wrapped around crowd-pleasing tales of lovers united and inheritances bestowed from unexpected quarters (a friend of mine calls this device "magic money"). Most of Dickens' characters occupy unequivocal positions in a binary system of good and evil. Written at a time when, in a bid for more power, the middle class was asserting its moral superiority over the decadent aristocracy, his novels present the bourgeois virtues of diligence, cleanliness, chastity, honesty, charity and familial devotion as the only means to a decent life -- not only for those classes below the middle, but also for those above.

The moral vision of "The Wire" is closer to Greek tragedy or the modernism of Kafka, which depicts the individual as mostly helpless in the face of larger, often unknowable forces. There aren't many Victorian novels that take this position, even if Elizabeth Gaskell's labor novels and Dickens' own "Hard Times" present the sufferings of Britain's working class with great sympathy. However, it's incorrect to state, as Robinson and DeLyria do, that "The Wire" is more "bleak" than any Victorian novel with the exception of "Vanity Fair." Several of Eliot's novels, particularly "The Mill on the Floss," George Gissing's "New Grub Street" and pretty much the entire oeuvre of Thomas Hardy (to name just a few) give the lie to that. Go read "Jude the Obscure" and then get back to me on the bleak thing.

Yes, I'm being disingenuous here. The equation of "The Wire" with Victorian novels has much less to do with any meaningful similarities between the two than it does with asserting the legitimacy of television dramas as what Robinson calls "timeless art." This is puzzling, as you'd be hard-pressed to find any sensible person who would challenge "The Wire"'s credibility in that front. Of course it's impossible to know which cultural works of the present will someday been deemed "timeless," but the HBO series certainly looks to be a solid candidate. There are still a few clueless souls out there who maintain that nothing produced for television can ever aspire to the status of Art, but like conspiracy theorists, they're determined not to change their minds and therefore no amount of evidence is sufficient to make them do so.

The difficulty in persuading more reasonable skeptics to try "The Wire" doesn't lie in convincing them that it's a lot like a Victorian novel. It really, really isn't, and I say that as a devotee of both. I review novels (among other books) for a living, and yet despite being enthralled by "The Wire" from its first season, I never once felt that watching it was like reading a novel, any novel. It's hard to sell novices on "The Wire" precisely because it's not reminiscent of fictional works in other forms, and it's also not like most serialized TV dramas. This is what makes it so remarkable. And, trust me, that's more than enough.

Further reading:

Promo page for "Down in the Hole: The unWired World of H.B. Ogden", published by powerHouse Books

Interview with Sean Michael Robinson and Joy DeLyria at the Atlantic Online

Shares