When the novel Cosmopolis first came out in 2003, it was regarded by most reviewers, myself included, as a disappointment. After the vaulting achievements of White Noise, Libra, and Underworld, Cosmopolis seemed like a return to the lesser DeLillo of Running Dog or Great Jones Street — as corrosive in its way as steam-punk, grimly absurdist, hopelessly nihilistic. It didn’t help that the novel, set in Manhattan, was published while the wounds of 9/11 were still fresh. Though the book (and the publicity materials at the time) made it clear the story takes place a year before the Twin Towers’ fall, a lot of us were picking through the book looking for pre-echoes of that tragedy. (His now-classic Harper’s essay of 2002, “In The Ruins of the Future,” had primed everyone for an extraordinary fictional treatment of the theme, though DeLillo didn’t get around to his 9/11 novel till 2008’s The Falling Man.) Re-reading Cosmopolis now, however, in the light of David Cronenberg’s new film adaptation, and given the context of the 2007 global economic meltdown and the Occupy Movement that followed, it appears to me that Don DeLillo has once again taken on the mantle of artist-prophet. Cosmopolis’s grimness — and it is Hell-dark, a near Miltonic vision of greed, chaos, and soul-squandering — is, it turns out, an altogether apt reflection of its theme, which is the remorseless momentum of post-Berlin Wall capitalism, of a New World Order that has no symmetrical foe aside from “terrorism” and which is wedded inexorably to technologies of such seamless, speed-of-light efficiency that it promises the very transcendence of the physical, an escape from mortality itself into the dream-realm of the cybernetic. As Eric Packer, Cosmopolis’s dread anti-hero, would have it: “He’d always wanted to be quantum dust, transcending his body mass, the soft tissue over the bones, the muscle and fat. The idea was to live outside the given limits, in a chip, on a disk, as data, in whirl, in radiant spin, a consciousness saved from void.”

The promise of technological transcendence is, of course, bullshit. It’s the postmodern version of Icarus flying his feather-and-wax contraption toward the sun, and we all know how that ended. But the Icarus myth speaks to psychic ambitions that maybe no amount of historical failure can squelch, and the contemporary version of it is perhaps more powerful than ever. Cosmopolis gives full voice to a promise of life lived in the hubristic confidence that the human limits of time and death can be eluded through one’s ownership and manipulations of technology — in fact, it gives us a central character who is in thrall to that idea. At the same time, it supplies our literature with the most trenchant critique of the soul-sickness of such a belief since, probably, Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, a novel it piggybacks in several ways. And in Eric Packer, it gives us a character of truly tragic dimensions.

The promise of technological transcendence is, of course, bullshit. It’s the postmodern version of Icarus flying his feather-and-wax contraption toward the sun, and we all know how that ended. But the Icarus myth speaks to psychic ambitions that maybe no amount of historical failure can squelch, and the contemporary version of it is perhaps more powerful than ever. Cosmopolis gives full voice to a promise of life lived in the hubristic confidence that the human limits of time and death can be eluded through one’s ownership and manipulations of technology — in fact, it gives us a central character who is in thrall to that idea. At the same time, it supplies our literature with the most trenchant critique of the soul-sickness of such a belief since, probably, Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, a novel it piggybacks in several ways. And in Eric Packer, it gives us a character of truly tragic dimensions.

2.

“For someone your age, with your gifts, there’s only one thing in the world worth pursuing professionally and intellectually,” Eric Packer tells Michael Chin, his “currency analyst,” as they inch their way west on traffic-packed 47th Street on the way to the barbershop where Eric insists on getting a haircut. “What is it, Michael? The interaction between technology and capital. The inseparability.” Mastery of that interaction has given the 28-year-old Packer his career as superstar asset manager, able to borrow and trade tens of billions of yen (updated to the Chinese currency of yuan in the movie) by tapping his finger on the tiny screens on his watch or the computer panels of his limo. That mastery has netted him his $104 million Manhattan triplex with the dual elevators, the shark tank, and meditation room. It’s provided him the opportunity to buy (and fly, once) an old Soviet nuclear bomber on the black market, and to marry a beautiful poet-heiress he barely knows. And it’s given him his bullet-proof, nearly soundproof limo, with its banks of computers instantly relaying streams of information that Packer and his genius team of financial analysts use, just as instantly (in not just nanoseconds, zeptoseconds), to manipulate markets and generate profits or losses so large they exist for him only abstractly. Eric’s in-dwelling in the super-rarefied world of abstract finance gives him the illusion that the material realm is irrelevant, archaic. (The names of things — like “Automatic Teller Machine,” even “Computer”— seem hopelessly outdated to him. He craves a world whose language is humanly denuded, and moves with the frictionless efficiency of cyberspace.) Even the limits of time and space seem to dissolve in the uncanny swirl of image and information he lives in. (The closed-circuit television screens inside his limo pick up what’s happening around his limo a few moments before it happens: his technology isn’t just instantaneous, it’s faster than reality. It’s one of the best jokes in the novel.) And of course, once time and space seem conquerable, one looks toward the final horizon, which is conquering death itself. As his chief theorist says, “People will not die. Isn’t this the creed of the new culture? People will be absorbed in streams of information.”

Now, if Eric Packer were a mere proponent of this creed, he’d be no more than one of Philip K. Dick’s more pulpy protagonists, dazzled by the digital imperative. But, as his nemesis Benno Levin tells him, “Your whole waking life is a self-contradiction.” Multi-billionaire Packer is haunted by “the stirs of a melancholy,” residues of humane memory that induce him to take, one April morning, a trip cross-town to the old-fashioned barbershop he went to as a child. And he’s animated by more than nostalgia: Packer is a slave to his body. Obsessed with his “asymmetrical prostate,” he gets daily doctor visits to monitor it. He is always hungry — he craves red meat, food that is “thick and chewy.” He’s also permanently on the prowl for sex, with his wife (who denies him), and with his female advisors and bodyguards (who don’t) — and he always reeks of it. Though he has sex several times during the course of the day — in 47th Street hotels, in the limo — it’s not enough. After a particularly vigorous coupling with his bodyguard, he asks her to fire her stun-gun at his chest. “I’m looking for more. Show me something I don’t know.” She complies, and finally, it seems, he gets some relief from the compulsions of mind and body: “The voltage had jellified his musculature for ten or fifteen minutes and he’d rolled about on the hotel rug, electroconvulsive and strangely elated, deprived of his faculties of reason.” But soon enough those faculties return, and he realizes that even electrification isn’t enough; he needs to court mortality itself: the flip side of his desire to escape into the digital is a fierce desire to confront his own death. (The self-contradiction comes, as it so often does, in the form of the return of the repressed.) The death-wish in him is abetted by the fact that his gamble on the yen is tanking: as the day proceeds, he loses his entire fortune, and by evening the losses have become intentional: he wants to be stripped of this vast money/technology that has protected him from himself. He is fascinated to learn that two financial titans — competitors, rivals — have just been assassinated, and thrilled that credible threats are being made against his own life. In a shocking moment, he kills his lead bodyguard, Torval, so that there will be nothing between himself and whoever is stalking him. And when he finally does meet his stalker — the soul-dead Benno Levin, who used to work for Packer and sees him as the embodiment of the techno-economic system responsible for destroying him — he not only shoots himself through the hand (it’s his final desperate attempt to feel) but allows Levin to raise his own gun to Packer’s head, where it is poised as the novel ends.

Packer’s tragic trajectory takes the form of an Icarusian plummet from Brilliant Young Turk to Absolute Zero. The tragedy also has a powerfully philosophical edge: Packer is like somebody dreamed up by Martin Heidegger to illustrate the peculiar despairs of technologically advanced civilization. For Heidegger, technology is exactly the distancing device that prevents us from achieving some full and direct encounter with the real — what he called Being itself. The “essence” of technology, Heidegger said, isn’t machines or systems of production, but a point of view that looks at reality only in terms of its instrumental use value: for example, it looks at a tree for the lumber it provides, not for the tree’s intrinsic tree-ness (its Being), or in Packer’s case, looks at, say, trading billions of yen exclusively as a game of profit or loss rather than something that has real-life effects on real-life labor, real-life consumers, the real-life environment. Looking at the world “technologically” is what alienation is, and Packer’s is the ne plus ultra of Heideggerian alienation. What’s worse, he knows it, and so in his despair designs an end for himself that will at last bring him some measure of contact with the real, even if it comes in the form of a bullet to the back of his head.

3.

The politics of Cosmopolis is just as rigorously despairing. The impotence of an oppositional left in the United States has been a subject of hand-wringing since the early 1970s, when Nixon crushed the McGovernite establishment, and the radical New Left fractured into farce, Weatherman terrorism, single-issue activism, and identity politics. But it wasn’t until the Berlin Wall fell, and the Soviet empire broke up in 1991, that the left was forced to confront the fact that it neither had a coherent philosophy of history nor a practical alternative to capitalist hegemony. This, of course, was the grand theme of Francis Fukayama’s The End of History and the triumphalist boast of George Bush’s New World Order. While oppositional energies occasionally gathered force — like the no-nukes campaigns of the late seventies and eighties, the Green movement of the nineties, or the Seattle demonstrations against the WTO and IMF in the late nineties (demonstrations which partially inspired the novel Cosmopolis) — nuclear proliferation, environmental degradation, and globalism march on. The Occupy Movement, in this light, seems only the latest marshaling of desperate leftist energies — heartbreakingly well-meaning, symbolically arresting, “raising the consciousness” of the 99 percent, but then petering out as it repeatedly hits the stone wall of capitalism’s entrenched barricades. We get a witty visual analogue of the idea in Cronenberg’s film. While Packer and his “chief theorist” discuss the “art of money-making” in his steel-reinforced limousine (“All wealth has become wealth for its own sake … Money has lost its narrative quality, the way painting did once upon a time. Money is talking to itself”), anarchist demonstrators rock the vehicle violently from the outside and spray-paint slogans on its immaculately white surface. But Packer and his theorist, knowing they’re completely safe, calmly sip their chilled vodkas and don’t register an iota of concern. The democratic idealism of a left movement dedicated to raising the consciousness of the masses to their own real interests and persuading people that capitalism can be sort of, you know, excessive and unkind is exposed as foolishly ineffectual. All opposition to the techno-capitalist nexus in Cosmopolis is reduced to loud but merely cathartic protest, symbolic gesture, and at its outer reaches, literal martyrdom, assassination and terror. It’s all impotence and despair. History’s done. Techno-capitalism won.

In Cosmopolis, anarchists storm into breakfast eateries, dangle huge dead rats in their hands, shout “A specter is haunting the world! The specter of capitalism!” then hurl them at the customers before running off. A “pastry assassin” named Andre Petrescu roams the world hurling crème pies into the faces of the famous and powerful, including Packer. These are the descendents of the Counterforce in Gravity’s Rainbow, absurdist performance artists whose political gestures are merely aesthetic — and thus harmless. Further along the anger-and-despair continuum, we have a demonstrator who immolates himself outside Packer’s limo, a gesture which the chief theorist dismisses as second-hand “appropriation” — as so Vietnam war that it’s not worth taking seriously. Then we have the bombers who rock the street outside the Nasdaq building and the assassins who kill a Russian billionaire and an IMF official. These actions, however, are also ineffectual: the street, we know, will be rebuilt, the financiers and billionaires replaced by others, the system unaffected. Finally, we have Benno Levin, who’s been calling in threats on Packer’s life all day. What is notable about Levin is that he’s a lone wolf. Disconnected from any larger social movement or solidarity with other people, his desire to kill Packer is merely personal, which is the kind of terrorism Americans specialize in: shocking, media-sexy, yet politically inconsequential in the extreme. The gun pointing at Packer’s head at the end of the book was fired long ago at the head of the American left.

4.

That a film as conspicuously critical of the juggernaut of global capitalism gets made in America at all seems amazing until you realize that Cosmopolis isn’t an American film. It’s true that director/scenarist Cronenberg has worked Hollywood money for decades, and the film’s star is the American pop idol Robert Pattinson, but the movie was funded by French, Canadian, Portuguese, and Italian production companies, and actually opened in Europe months before its premiere in LA and New York in mid-August. The American reviews have been predictable: the pop critics at, say, USA Today or The New York Post have been insulted or bored by all the film’s probing rhetoric about capitalism, while a few more thoughtful critics (like Amy Taubin at Film Comment) get what DeLillo and Cronenberg were after. I, for one, found it refreshingly bizarre to sit in a beautifully appointed West LA theater with stadium seating and five dollar mini-bottles of mineral water for sale in the lobby and hear lines like this: “Time is a corporate asset now. It belongs to the free market system. It is being sucked out of the world to make way for the future of uncontrolled markets and huge investment potential.”

Cronenberg has been scrupulously faithful to the thrust of the novel’s ideas. He has cut a scene or two, put dialogue into a character’s mouth that comes from Packer’s internal monologue, and here and there underlined a concept with less than DeLilloan subtlety, but that’s screenwriting for you, and I can’t help but think that DeLillo must be happy with his director-scenarist. Yes, the film is talky, it is claustrophobic; the general atmosphere hovers close to dreaminess, and except for one sex scene featuring the redoubtable Juliette Binoche and the long final scene with the even more redoubtable Paul Giamatti, the film has the static camera and antiseptic quality that one associates with Stanley Kubrick. The explosions of violence are exquisitely prepared for. The serious exchanges about theory or economics aren’t mumbled or rushed, as they might be if Cronenberg were afraid he’d lose the audience, or was himself uninterested in the ideas. We’re not supposed to sit there and be awed by the smart talkers, or, conversely, dismiss them as pretentious bullshitters. The deliberate pace of the dialogue, and the frontal camera placement, which often gives us nowhere to look except the faces of the speakers, insists that we consider what they’re saying. Some viewers will find the utterances of Packer and his team of advisors infuriatingly gnomic. The scene with Samantha Morton, it’s true, is unfortunate: Morton plays Vija Kinski, the chief theorist, and she delivers her lines — important lines, too — with the annoying archness of an embittered PhD student who can’t find a tenure-track job. Twilight fans looking for a Robert Pattinson fix will slink out of the theater feeling slugged by perplexity. But that’s all OK. For those with ears to hear and eyes to see, Cronenberg’s done justice to the hard poetry of DeLillo’s bleak vision.

There is the question of whether Pattinson pulls off the lead role. I’ve seen none of the Twilight films — I’m innocent of his media allure — so the worst thing I can say about his performance is that he’s not Christian Bale, whose imposing physicality and cruel intelligence would have been perfect for Eric Packer. Then again, it’s probably Pattinson’s name that allowed the film to get made at all. He starts out shakily: he tends to use a forehead-wrinkling stare when he’s trying represent complex thinking, and some of Packer’s superarticulate lines are delivered in a way that sounds callow for a guy who supposedly spends his free time reading Zbigniew Herbert, much less has consistently beaten the markets to the tune of $30 billion. Intellectual brilliance is one of the hardest things for any actor to fake, but Pattinson grows into the role enough that he doesn’t embarrass himself. By the end of the film, in fact, his youth actually helps: staring at the camera with a gun pointed at the back of his head, his Packer looks convincingly overwhelmed by confusion and terror — the way anybody, market demigod or not, might.

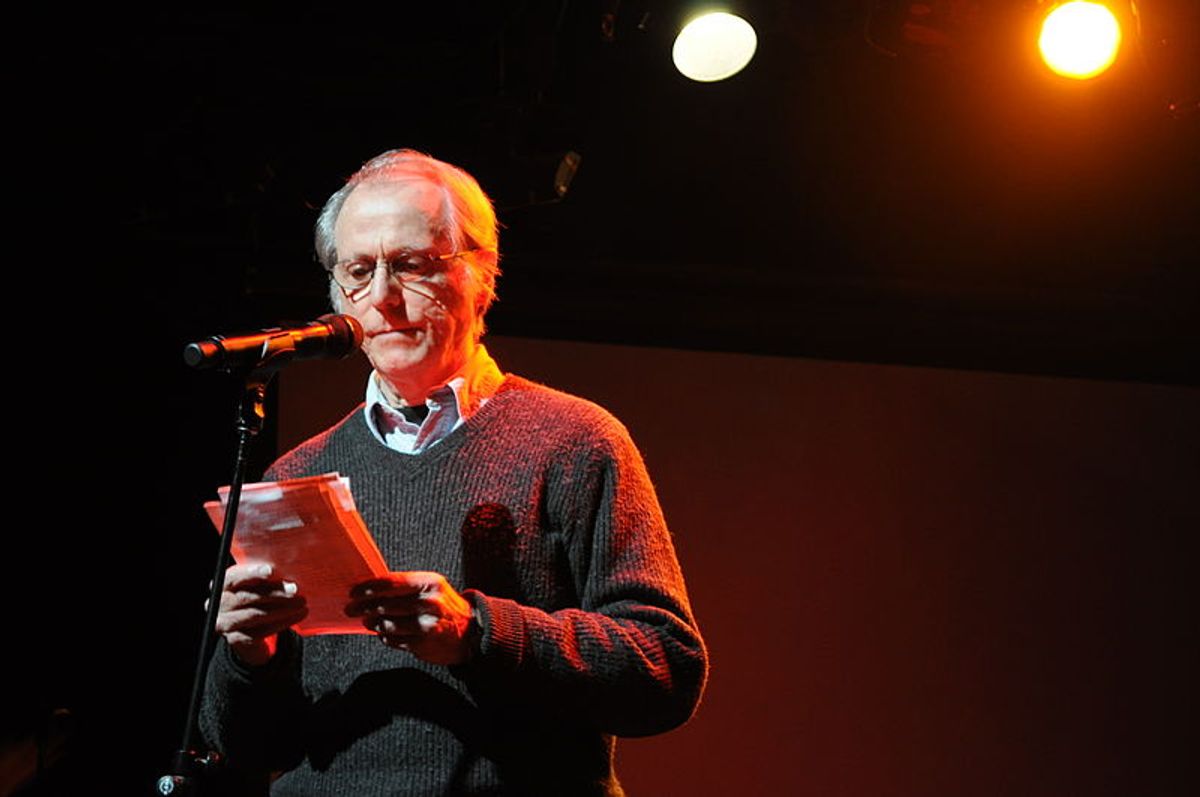

Not every scene works. Cronenberg doesn’t quite have a feel for DeLillo’s dark humor — a scene where Packer tries to seduce one of his analysts in the limo while he’s getting a prostate exam (yup, you read right) falls flat, as does another scene where two cab drivers — one from Manhattan, another from Senegal — compare histories. But this is quibbling. Cronenberg is one of the few directors working in America who has the patience and respect for ideas that Cosmopolis demands. To bring those ideas, more or less intact, to the multiplexes is no small feat, and will, one hopes, gives renewed life and attention to a novel that tells us more about this culture’s hurl into the future than we want to know. Forty years into an astonishing career, DeLillo remains our contemporary exemplar of the “antenna of the race.”

Shares