Imagine a woman being able to convert her own eggs into “pseudo-sperm” to fertilize herself – or perhaps instead an artificial womb that will carry the pregnancy to term while she continues her uninterrupted climb up the career ladder. Picture an older woman harvesting eggs from her own bone marrow to beat her ticking biological clock.

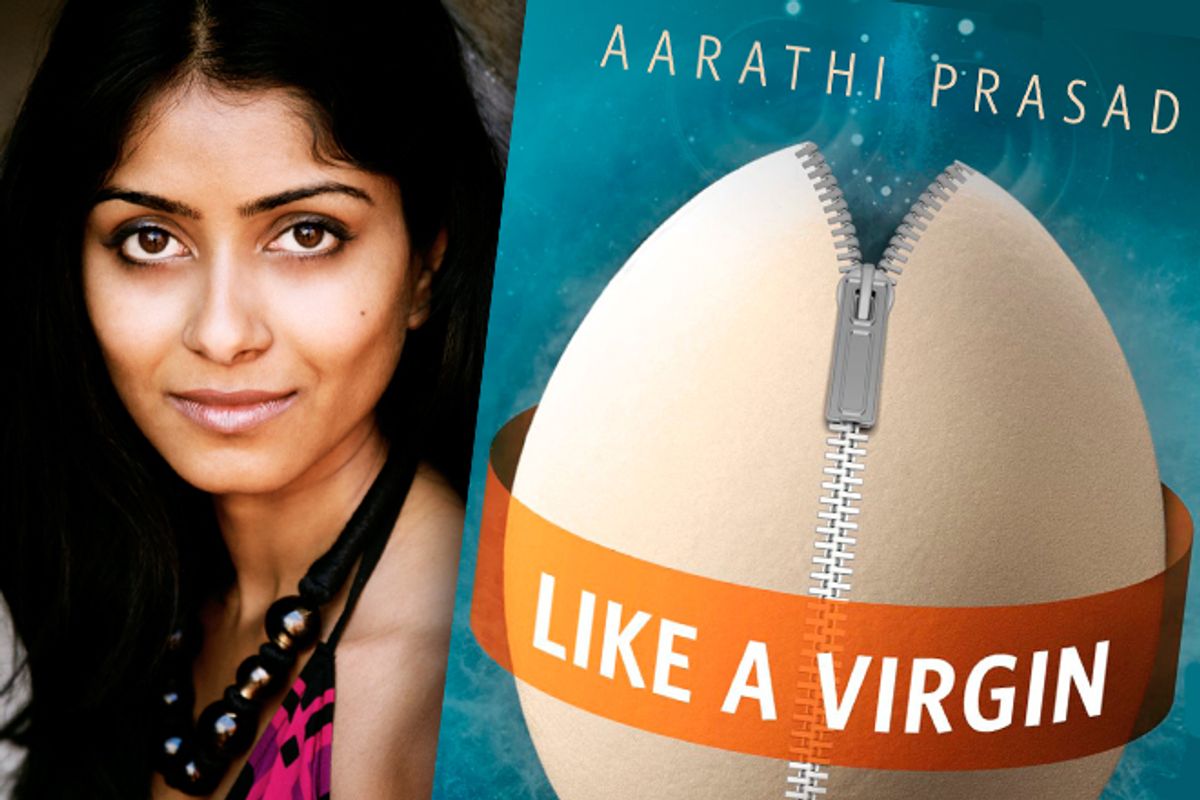

Lifelong fertility, artificial wombs, “pseudo-sperm” – it sounds like the stuff of dystopian sci-fi, but a new book suggests it’s an inevitable reality. In “Like a Virgin: How Science Is Redefining the Rules of Sex,” author Aarathi Prasad writes, "This would be the great biological and social equalizer, a truly new way of thinking about sex. The question is not if it will happen, but when." It isn’t just women who stand to benefit, either: Artificial wombs will actually give men "more potential than women to make a baby without the opposite sex,” says Prasad, a biologist and science writer. The takeaway is that "male plus female equals baby will no longer be our only path forward.”

The potential social implications of such advances are fascinating, but Prasad leaves those imaginings to the likes of Aldous Huxley. She's more concerned with reviewing how our reproductive knowledge developed and what technologies are being developed -- but in a relatively digestible way (more Jared Diamond than Jonah Lehrer). That said, Prasad cautions against future-panic, arguing that these developments could actually improve on current ethical quandaries around reproduction. For example, which is less morally fraught: stem cell eggs and artificial wombs, or paying a poor woman in a third-world country as an egg donor or surrogate mother?

Prasad spoke to Salon by phone from her home in London about everything from "lesbian lizards," virgin births and greatly exaggerated reports of the Y chromosome's death.

It’s bizarre to think of a time when we didn’t know what sperm was. More amazing still is that even when it was discovered that female mammals produced eggs, it was assumed they were merely meant for incubating the all-important sperm. Why was that such a great conceptual hurdle?

That’s a good question. I think the idea went back to ancient Egyptians and ancient India. For long periods of history, human dissection was proscribed -- and even when they did it, they didn’t have women. They really didn’t have a good understanding of the female body. When they dissected men, they assumed that women’s organs were some kind of lesser version of the males'. So it may have been, even when these scientists were looking down microscopes and seeing eggs or seeing that there were insects that reproduce without males, they were just unable to entertain the idea, that what could really be happening challenged the ideas that they were so used to. They saw what they wanted to see. It just fit into their social ideas, so it wasn’t challenged.

You point out in the book that it’s a bit odd that women reproduce sexually, since it isn’t “optimal for them or their progeny” (as more-plentiful sperm are more likely to pass on harmful mutations). So why do they -- or we?

The best answer to that would probably be “to give increased genetic variety.” If you had a characteristic that was beneficial that one individual in a population had, and another one that was good that another individual in a population had, and they were just going on reproducing themselves without mating, then there will never be a chance that those two good characteristics come together in one individual. You have the option to have that much more variety when you do mate, and this can have huge advantages in adapting to new environments, like if new parasites came in or something. You would have more options in your genetic instruction book to choose from. Having said that, there are animal species that have reproduced millions of years without males, and it’s not always through cloning themselves. There’s not a one-size fits all. There’s a weird and wonderful array of ways that females, with and without males, choose to do it.

There are these lizards called “lesbian lizards,” because they don’t have any males. They originally came about when a male from a related species and a female from another related species mated; their daughter was a mutant and she had the ability to reproduce without males. They do this strange mating ritual where one female mounts the other, and the female that mounts looks and acts very much like a related male would in a mating ritual, where she’s the aggressor and the other female is very passive. They rub their cloaca together, which is their orifice that they use for reproduction. When you dissect them after that mating ritual, what you find is something very interesting: the female that was acting as the male, nothing much is going on with her eggs, but the female that was acting in the female role, her eggs were ready to become baby lizards.

A whole animal can be built from an egg -- that’s why we see all-female species but you never find an all-male species; it’s not possible because the sperm is essentially packets of DNA, but an egg contains all the rest of what you need to create a new animal.

You can imagine that, yes, you have less genetic variety, but if the choice is to not reproduce at all or to reproduce with less genetic variety, than I guess for endangered species it’s probably a good strategy to have. There are all these strategies for reproduction in nature, and it’s something maybe we can learn from.

Is it possible, hypothetically, for human females to reproduce asexually?

Naturally? No, it’s absolutely impossible, because there is a genetic mechanism whereby certain genes in the male genome and the female genome are locked, and if they’re locked in the male genome then they’re not locked in the female, and vice versa. A lot of these genes that I’m talking about are important in the development of the placenta and the brain, so it’s absolutely necessary to have two parents -- one male, one female -- in order to get a viable child. If you try making a baby from two female eggs, and they did this with mice, the embryo would be OK but you’d never get a placenta because the DNA for the placenta actually comes from the father.

It’s almost like if you had two copies of a book and in one copy of the book page 9 and 11 were unreadable, so you had to turn to your second copy to read page 9 and 11. That means you need both books to decipher the entire narrative arc, and that’s what it’s like with humans -- and all mammals, as far as we know. We think that’s the case because fathers in nature will come along and mate and then go off again so the investment in the baby is backed up if they are able to dictate the genes that nourish the baby. So they want the baby to grow bigger and healthier and stronger and take as much resources from the mother as possible, and the mother, on the other hand, doesn’t want one child to take too much of her resources because she needs it for herself and for other children that may have different fathers. So it’s a kind of battle for resources, that’s why they think it’s developed. That’s significant for humans, particularly, because we have very big brains and therefore the rationing of resources becomes very, very important.

There is these things called ovarian teratomas, which are essentially women’s eggs just going ahead and developing on their own -- but they never get very far. In these ovarian teratomas, you get skin, you get hair, you get nails, you get all manner of body parts. But they never grow into real babies, because they will never be able to form a placenta because they have no father’s DNA.

Where do we currently stand with artificial womb technology?

That’s been quite hard to find out, actually, because scientists have been attacked for talking about it, even though the reason they’re doing it is because there are actually a ridiculous number of women who are born with damaged or deformed wombs and will never have a chance to have a baby naturally. But the whole [Aldous] Huxley concept of “Brave New World” comes up, sort of imagining babies being farmed in dystopias.

What we do know is that there have been incubators that have been able to keep fetuses from other animals – goats, for example – alive at very young ages. An artificial womb is essentially pushing back and back the age at which you can keep a fetus alive and healthy. An artificial womb has been created for a relative of the grey nurse shark, but sharks’ placentation and how they grow in the womb is a bit less complicated than in humans. It’s a huge challenge, but work has been going on with goats’ fetuses with uterine tissues – in dishes in the lab, but still, they’ve been able to create womb scaffolding. It goes some way toward laying the groundwork for creating a place outside the body in which a baby could potentially grow. So on one side of the research that’s going on it’s to look at how to keep babies alive when they’re born prematurely; on the other side is how to make fertilized eggs implant in the womb. I don’t think it’s beyond the capacity of technology.

People say, “What about bonding?” but already women use surrogates, already adopted parents bond with their children. In some countries, surrogacy has become a kind of boom industry, and the women who do these things -- I’m talking egg donations and renting their wombs out to become surrogate mothers -- are doing it for economic gain, and because they feel like they have to. If you had the availability of artificial wombs, ethicists have told me it’s going to be very hard to argue that you shouldn’t use this artificial womb instead of paying a poor woman in Ukraine or India to do that for you. It’s quite hard to tell, I don’t know how far into the future we’ll have one, but I do know that it’s definitely underway, and people aren’t talking about it.

What sorts of wild reproductive technologies can we anticipate in the future?

For me, the most interesting ones are the ones that might change the status quo for women in terms of our reproductive clock. Just because we go to school the same as men, we work the same, we spend most of the fertile years of our lives building our careers like men do, but then we hit this abrupt end of our fertility that men don’t really have. That stopping of our reproductive potential goes along with increased risk of heart disease and osteoporosis; some doctors consider it an organ failure just like any other, and it has a lot of impact for women throughout life. So I wonder about technologies that will allow women to have healthy eggs throughout their lives.

The reason why scientists were trying to create sperm and eggs from bone marrow stem cells is because if you really want to understand how something’s made and what goes wrong with it, the best thing to do sometimes is to try and create it from scratch. What they found is they can generate eggs from female bone marrow, but what’s very interesting is that they can generate both sperm and eggs from male bone marrow stem cells. Scientists have told me that this could be in clinical use in about 15 to 20 years' time. It could change what families look like, because you could see a situation where a gay couple or a lesbian couple for the first time ever in history has a child that’s genetically their own. It also means that as a woman gets older, even as her supply of eggs may not be very good, she can still generate her own genetic eggs rather than getting egg donors.

In recent years I’ve seen a lot of headlines about this: Is the Y chromosome really headed toward extinction?

No, not strictly, because the degeneration of it has slowed down considerably. It did degenerate an enormous amount, there’s hardly any genes left on it, so I guess you could say the genes that are left on it are absolutely essential for maleness. However, even if it did disappear, there are a few animals the males don’t even have detectable Y chromosomes, but they’re still male. There’s only about two regions on a Y chromosome that are essential for being male, and what happens in these animals is that these bits of the Y chromosome have jumped onto another chromosome. It does mean that they’re less fertile but humans aren’t very fertile anyway. A man and a woman in their 20s, peak fertility, having unprotected sex have only about a 20 percent chance of achieving pregnancy.

Infertility seems to be on the rise in certain countries and that’s related to the older age at which people seem to be having babies, but it could be related to other things as well that are happening in men.

Why is our biology so unkind when it comes to reproductive timing and age?

That’s another good question. There are some hypotheses -- one is called the “grandmother hypothesis.” That’s that if grandmothers and their daughters are reproducing at the same time, then there’s competition for childcare, and the best predictor of a child’s survival, we’re talking historically, was a mother’s care and and the maternal grandmother’s care. Bear in mind that women often died in childbirth, so the maternal grandmother was key.

You can imagine a time in the past where you become reproductively active in your teenage years -- I mean this still happens all over the world -- and you were probably long dead before menopause was ever going to happen. So, I think evolution hasn’t caught up with our lifestyle changes. You’re asking about the individual disadvantages, but sex is very much something that benefits populations, not individuals. But humans are individual and we increasingly want a family when we want a family.

One of the best indicators of women having babies later in life is education, and the more educated a woman is, and the more time she spends with her career, that means she’s leaving [having a baby until] later and later. And we don’t want to go backward and say, “Well, girls shouldn’t be educated,” so what’s the solution? It has to be social. After World War II, in the U.K. every workplace had childcare in it because the men were off on the front and they needed women in the workplace. So it’s almost like by not doing that now, our government is saying, “Well, we don’t absolutely need women.” If there was cheap or free childcare, that would change the way women worked and had families.

So there are possible social interventions, but it’s also inescapable that our biology is not the same as men -- and it’s kind of unfair that ours stops when we are in the prime of life.

Shares