We are drowning in polls and predictions. Whether it’s politics, sports, economics or even the weather, there’s more information and data than ever. But how much of it is white noise? How many of these predictions have rigor and mathematics behind them, and how many mask uncertainty or ideology behind the seeming exactitude of numbers?

In 2008, Nate Silver built a near-perfect model for analyzing the polls at his web site Fivethirtyeight.com. Silver called Obama over McCain in March — and ultimately nailed 49 of 50 states, got every Senate race right and predicted the popular vote within a percentage point. That’s the kind of predictive power we all dream of when we fill out NCAA tournament brackets or a lottery ticket. The New York Times added his blog to its site soon after the election. The numbers geek started a bidding war.

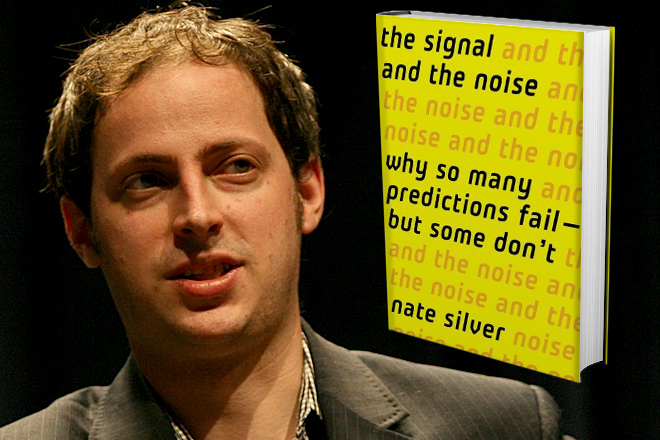

In his new book, “The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail — But Some Don’t,” Silver tries to explain the secret to getting things right — and finds that it often turns on blind ideology and overconfidence. (He’s gotten things wrong himself; in the book, Silver admits that his much-touted baseball statistical analysis system, called PECOTA, actually fared worse than the collective wisdom of the old-school pro scouts, much-maligned in the “Moneyball” era. Hey, he still totally got Dustin Pedroia right.)

And while it’s not that important, in the end, to predict the state-by-state Electoral College winners, Silver sits down with national security and economics forecasters, as well, who have similar jobs as him in some ways — searching through the clutter and distractions to find the information that matters.

As national and state polls began swinging in President Obama’s favor this week and Romney partisans began trying to discredit the objectivity of the results, Silver met with Salon in a coffee shop downstairs from the New York Times to talk insider political baseball. (The interview has been edited and condensed.)

Fox News and Romney supporters this week have turned on the polls. As more and more of them show the president opening up a wider lead, both nationally and in many of the major swing states, they’re essentially charging that there’s liberal bias both in the way these polls are conducted and in the way they are reported. Is there any truth to that?

At that point, you literally are alleging a conspiracy, right? And you get these headlines on Fox News like: “Poll is biased toward Obama.” I think they maybe make too much of that on the conservative side.

I saw Dick Morris on the “Hannity” show last night. He wasn’t just saying Romney still has a chance; he was saying it’s a toss up, which I don’t quite believe. It’s getting a little more ridiculous the more polls that come out. But he was saying, “I think Romney will win by four points. I think he’ll win Pennsylvania and would be competitive in Michigan.” You have to be totally delusional to think that. Is he out of touch with reality? Or is he lying?

I mean, there is literally a web site right now that is devoted to the premise that the Rasmussen poll, which tends to (favor Republicans) much more than anything else …

Right, Unskewedpolls.com …

It’s the purest example of a selective reading of the evidence that you can possibly find. Rasmussen has the race tied right now, I think. And Unskewedpolls has Romney up eight, right? When I used to play poker, if someone is that out of touch with reality, at least you could bet them money. At the same time, sure, the polls could be skewed. But they could be skewed in either direction.

So if the polls right now tend to show Obama up, say by five or six, that could still be within the margin of error. Could these polls we’re looking at be wrong?

Sure. One poll that shows a five-point race doesn’t really tell you much. But since the conventions we’ve had, I think, 250 polls released — state polls, national polls — and that really reduces the margin of error to very little.

Look, you have about 10 recent national polls now, which is a fair number, certainly. But you also have 100 state polls that have been released over the last week from a more diverse set of pollsters. And again, we’re not talking about huge shifts, right? Where the state polls say Romney’s down by five instead of being down by four — it’s not that precise where that’s really all that much of a difference.

But it’s not like there is a fundamental disagreement there, exactly. Today, for example, the Gallup poll now has Obama up by six and a Bloomberg poll has him up six. So you have two more national polls to say, “All of the national polls seem to be in line now.”

When we are surrounded by predictions and drowning in polls, how should people test the validity of what they hear? What’s actual analysis, and what’s politics and spin masquerading as prediction?

On average, people should be more skeptical when they see numbers. They should be more willing to play around with the data themselves. And, yeah, that might lead to the occasional Unskewedpolls.com, but look, the application there is really wrong, but the instinct that you should be willing to take data skeptically is worthwhile.

But that’s the good thing about predictions. Someone like Dick Morris makes predictions that are specific enough that you can test them and see how they do, right? But what usually happens is people make a prediction, and then it’s right or it’s wrong — but either way it’s forgotten and you’re on to the next one.

There is no substitute for having an actual track record of having made predictions. Basically, some predictions are no better than random, right? And some are worse than random.

So why are we so fascinated with predictions? All day long, the 24-hour news networks are making projections. Sports radio and ESPN analyze the likelihood of teams making the baseball playoffs down to a tenth of a percent. We can’t get enough of trying to guess how things are going to play out.

I have two answers to this, and maybe they’re complimentary in part, contradictory in part. I think, on the one hand, you can go to a site like FiveThirtyEight and it has that one number, right? So Obama today has a 79-point-whatever-it-is [chance of winning] — 79.6 or 79.7 — and that might save you a lot of effort; it’s like, here’s the gist, right?

I think people feel like there are all these things in our lives that we don’t really have control over. Certainly, one person’s vote doesn’t affect the political environment very much, and I think we feel like if we can predict something, we can control it. And so, getting into that data allows us to feel less alienated from the random course the world might be on, or the inability to influence it.

I also think there is a little bit more of a do-it-yourself spirit now, which helps. People don’t necessarily trust the news media to mediate information for them anymore — and maybe they shouldn’t, right? So if you show the raw numbers and are actually willing — at least in my case — to set a betting line, basically … And it’s based on a formula you’re not just making up a number everyday.

In the end, it does boil down to the numbers. Right now, you can say Obama’s the favorite, but Romney is not out of it, right? I think everyone can agree with that. But what’s “not out of it”? Does that mean he has a 3 percent chance? A 5 percent chance? It’s that margin between the 5 percent and the 45 percent chance where I’m trying to make my trade.

Do we poll too much? Or pay too much attention to the results?

Maybe. I think there are definitely diminishing returns. Part of what we’ve found, as well, is that the more polls you have in any one state, the more they converge, which shouldn’t happen statistically. It reflects the fact that once there is a consensus of what’s supposed to happen, then most polls just want to stay within that consensus. Polls just start using chintzy methodology that will just calibrate to the pollsters who were good. What we find is you get to go from one poll to two, two to three, three to four, that helps a lot. After that, you really start to encounter diminishing returns.

You can have catastrophic errors from time to time. And, you know, we could have one of those this year; obviously Unskewedpolls.com thinks it might be in one direction. But if the independence of pollsters is compromised, that makes everything more difficult. I do worry sometimes that this tendency for pollsters to herd together has picked up since about 2004, when RealClearPolitics came online.

Best case: people are cheating off one another when taking the test, and you have to adjust. That’s why I started going back and evaluating pollsters on quality-related factors. Are they following industry standards for disclosure? Are they calling cell phones? Those are two basic ones. So it’s not too complicated, but that gives you some sense for who is doing polls the traditional way and who isn’t. It used to be, well, there wasn’t much difference between what the traditional polls did and what the newer ones did, so of course they got the same results. But now you do see a divergence — and we’ll see a big test of it this year.

As important as it is to predict baseball playoffs and election results, you’ve got a lot of other examples in your book of perhaps more serious predictions where the decisions made by expert analysts really matter: recessions, the housing bubble, terror attacks. And lots of these experts don’t have better results than John McLaughlin or Dick Morris.

Economic prediction is very, very tricky. When you say GDP grew by 1.7 percent, that figure has a margin of error based on the actual revisions of plus or minus three or four points worth of GDP. It’s hard to know where we are today. But in economic forecasting, you don’t seem to see much self-awareness of that. At least when we have a poll, people say here’s the margin of error. That is sometimes misinterpreted.

But economists might say that there will be 115,000 jobs created next month — and on average that figure misses by 70,000. That’s a huge miss, right? Really it’s fairly average for it to be off that much. Because in economics there is so much data, I think people feel like you can be very precise about these things. And some things you can’t; some things just aren’t predictable beyond a certain degree because they have an intrinsic complexity and they’re evolving fast. Whenever you have dynamic interactions between 300 million people and the American economy acting in really complex ways, that introduces a degree of almost chaos theory to the system, in a literal sense.

But sometimes the prediction system is rigged: As you note in the book, the housing collapse, in part, was made worse by untrustworthy predictions made by agencies and rating companies we assumed were neutral players but which, in fact, had a financial interest that placed a thumb on the scale.

Yes, there are these elements of subjectivity that creep into model design. And more in some fields than others, but that’s the case. We are taking these new instruments, and the choice of assumptions is going to make a huge amount of difference. And if you have not just a personal leaning, but a direct financial incentive to prop these up, there is almost no way that you are going to be able to overcome that.

Back to the campaign: Can Romney overcome this deficit?

It’s not hard to say Obama’s ahead right now. The question is: How much of an underdog is a candidate who trails by four or five points on September 26, relative to November 6? That seems more interesting to me; it’s a harder question.

We have him at about an 80 percent chance of winning reelection. Go back and look at who was ahead in the Gallup poll dating back to 1936 at this point in time — and 18 of the 20 won. The exceptions were Gore versus Bush and Dewey versus Truman. But the thing that is very hard to do in predicition is calibration — if you say there is a 20 percent chance of rain, then over the long run you are expecting it should rain 2 out of 10 times. And that’s what people don’t get. Right now we have Obama as an 80 percent favorite. Well, the underdog should win 20 percent of the time. One out of five. Otherwise you say he is a certain favorite.

Should this have been a closer election? You had this much closer to 50/50 earlier in the race.

My intuition in May had been that it’s a 50/50 race, not in a figurative way but almost literally. But the model came out with a 60/40 Obama edge. Not a huge difference, right? But it went against my intuition a little bit, and I scrutinized things. The main difference was that with the national polling data versus the state polling data, Obama has basically always been ahead in the most important swing states or in enough swing states to win the electoral college. There have been moments when national polls have been almost tied, but there’s been almost no point this year at which you could say that Romney’s ahead in Ohio or Pennsylvania or Virginia. And now we’re seeing the national polls starting to match the state polls more.

Do you have a best guess on Congress yet?

I don’t have the House forecasts up yet. My hunch is that we’ll have the GOP with on the order of a 70 percent chance to retain control. And I could be wrong. If I publish this next week and it says 5 percent or 50 percent, don’t blame me!