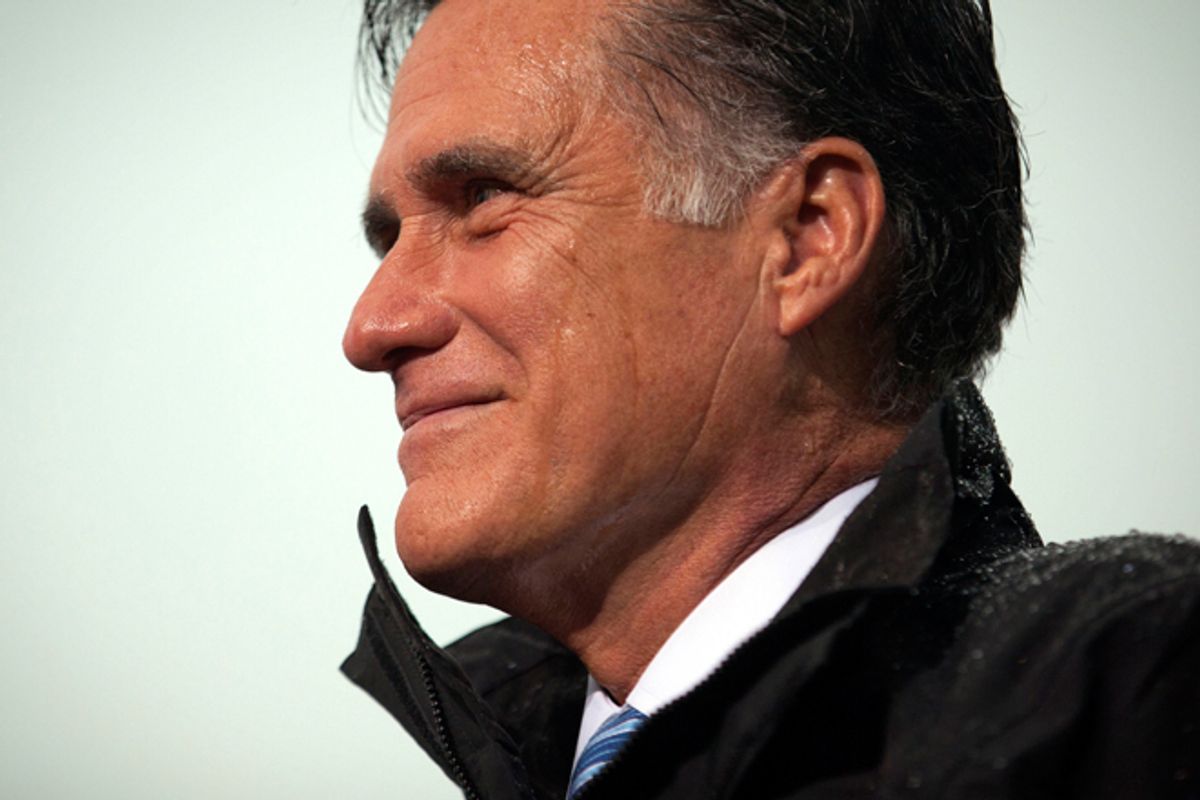

Mitt Romney gets a lot of guff from his critics for his unwillingness to spell out the details of how he plans to fix the U.S. the economy; how exactly his tax reforms will work, for example, or what precisely he will do in his first 100 days to boost job creation. But the best thing about the Romney agenda is that by his own admission, he doesn't need a plan. Just getting himself elected is the ticket to prosperity.

Romney was quite clear on this point in his infamous "47 percent" speech. Romney told his audience that "if we win on November 6th there will be a great deal of optimism about the future of this country. We'll see capital come back, and we'll see -- without actually doing anything -- we'll actually get a boost in the economy."

The notion that Romney could spur economic growth "without actually doing anything" invites mockery. The Atlantic's Matt O'Brien memorably dubbed it "faith-based economic strategy." At the very least it seemed to betray a breath-taking level of unwarranted hubris. But the key to understanding his boast is to ignore the low-hanging fruit ("without actually doing anything") and focus on five crucial words: "We'll see capital come back."

Romney is referring here to the reluctance of corporations to invest trillions of dollars of cash in productive, job-creating uses. It's a problem acknowledged by both Democrats and Republicans -- American corporations have around $1.8 trillion in cash tucked away in savings accounts or invested in low-yield bonds and ultra-safe government securities. Liberal-minded economists believe that corporations are sitting on all that cash because they see no demand in the general economy for their goods and services. Conservatives argue that the real problem is the prospect of higher taxes and burdensome regulations imposed during a second Obama term.

In fact, conservative pundits and politicians have been arguing for at least a year, to borrow Speaker of the House John Boehner's felicitious phrasing, that the "job creators in America basically are on strike." They're uncertain about the future, and, as conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer argues, "when you don't know what's going to happen, you don't invest. We are having a capital strike."

Romney advisor John Sununu put it bluntly in July:

"I guarantee you that what we are seeing in the private sector is a hoarding of capital. They are waiting to see the results of the presidential election... If President Obama is elected, that capital goes offshore. If Mitt Romney is elected, they buy equipment and they start hiring here."

If Mitt Romney wins, in other words, "the capital strike ends."

---------

Let's be honest. It's not impossible for a change in leadership to spur an economically fruitful change in psychology. After all, it was none other than the liberal hero, John Maynard Keynes, who stressed the importance of "animal spirits" in the economy. Human emotion is a crucial part of consumer confidence. If we're feeling good, we're more likely to pull out our credit cards and splurge, thus creating the essential demand that fuels economic growth. If we're feeling uncertain or anxious -- whether about our prospects for keeping our home, or for the quarterly earnings of the corporation that we might leading -- we'll be more cautious.

Here's how Keynes defined it, in his classic, "The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money": "A large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than mathematical expectations, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive... can only be taken as the result of animal spirits -- a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction...."

So let's be charitable. Maybe all Romney is saying is: If I'm elected, the animals will be happy. People will feel better about themselves, and that will jumpstart the economy.

The funny thing is, the available evidence suggests that Americans are already feeling more optimistic than they've been for a long time. On Friday, the University of Michigan's consumer confidence index hit a five year high. Americans are buying cars at a pace not seen in four years. They're watching their homes appreciate in value for the first time since the bust. Retail sales are growing. Average Americans are doing their part, and the ironic truth is that, most likely, no matter who gets elected president, they'll probably keep doing so. Neither Romney nor Obama might have to do anything at all in order to enjoy the benefits of a resurgent economy.

Even funnier, the premise that a Romney election will "bring capital back" presupposes that capital has gone away. And despite all those stories about trillions of dollars of "cash on the sidelines" there is scant evidence that a lack of investment opportunities or abundance of regulations is the reason for the hoarding. In fact, it's not even true that corporations aren't willing to invest in the future.

Quite the opposite. Here's something you are unlikely to hear during a Mitt Romney stump speech. Business investment has actually recovered to its pre-recession levels. During the Obama recovery, corporate spending on business equipment and software has grown at a faster rate than during any of the last four economic recoveries. (George Bush's economic recovery, embarrassingly, registered zero net growth in business equipment and software spending.)

What those companies haven't been doing is hiring. And there's a very good reason for that: the economists who point to the problem of demand are right. At least, they're right if you trust the reports of actual business executives. For three years, the number one complaint cited by small businesses about the current economic climate has been poor sales. Not taxes, not regulation -- sales.

Corporations and businesses with an eye to the future had no choice but to buy new computers and other business equipment and new software -- during the crunch of the recession, they cut spending so severely that at this point they would be jeopardizing their ability to function efficiently if they didn't start upgrading. It would have been suicidal to put that off, placing them in a disadvantageous position once the economy started to grow again. But without consumer demand for goods and services, without people walking into stores ready to buy things, there was still no immediate justification for boosting employment rolls.

Interestingly, just in the last month, the number of small businesses citing poor sales as their top complaint dropped into a tie with taxes and regulation -- yet another sign that consumer activity is beginning to bubble. And that presents us with an interesting mystery. In 2012, as consumer confidence has grown, with spending in stores rising and auto sales booming, the rate in growth of corporate spending on business equipment and software has actually slowed. Over the last few months the totals for "durable spending" -- big ticket purchases usually made by corporations -- have also been disappointing. We're watching a split personality at work -- average Americans are becoming more optimistic while corporate America is becoming more pessimistic.

What's wrong with corporate America? Don't they see home prices rising and car sales booming? Isn't it nicer to have steady, albeit weak, job growth instead of the massive hemorrhaging we saw four years ago?

The answer may lie in politics more than in reality. The most obvious explanation for corporate pessimism is the oncoming "fiscal cliff" -- the combination of mandatory spending cuts and tax hikes that will kick in if Congress and the White House do not hash out a deal before January 1. Severe fiscal austerity combined with the expiration of all the Bush tax cuts (as well as several additional stimulative measures, such as Obama's payroll tax cut) will be a kick in the ribs to the U.S. economy. A kick that breaks ribs.

Everyone knows this, and neither Democrats nor Republicans want it to happen. Romney even referenced the possibility in the same passage in which he boasted about how he didn't have to do anything to improve the economy -- "my own view is that if we get the -- the 'Taxageddon,' as they call it, January 1st, with this president, and with a Congress that can't work together, it really is frightening, really frightening in my view."

Romney is not wrong. A congress that can't work together in the face of a fiscal catastrophe is a scary, scary prospect. But here's the thing, to avoid that eventuality requires doing something. Just the fact of Romney getting elected isn't going to change any business executive's attitude toward the impending fiscal cliff. Hammering out a deal is the only thing that will unlock the checkbooks.

And here's the irony -- the average Americans, the ones who apparently aren't paying any attention to the oncoming plunge, are actually demonstrating a savvy understanding of politics superior to the executives who are cowering in fear. Because if there's one thing we should have learned while watching Congress operate the last four years, it's that no deal gets done until the last second... but, eventually, it does get done. Congress won't let us plunge over the cliff. There will be lots of rhetoric, and lots of arm-twisting, and the exact nature of the compromises that will be made will shift according to who wins the White House and the changing balance of power in the House and Senate. But it will happen.

Unless, of course, Mitt Romney gets elected and doesn't actually do anything. Then we'll all suffer. And the animals won't be pleased.

Shares