Say it with me: Are women funny? Since this question was first answered in the negative in the pages of Vanity Fair by the late, redoubtable Christopher Hitchens, it seems to have been designated by the chattering classes as one of the great unanswerables of the universe, destined to be dredged up every time someone’s looking for page hits by pissing off the wrong person at some heavily trafficked and influential ladyblog (#sorryfeminists!). To everyone else, this may seem like a settled a matter of simple logic: Women are human beings (no matter what some Republican members of Congress might believe); some human beings are endowed with an innate talent to make others laugh; ergo, some women are funny. The end.

And yet, it is with this specious query (if there is a God, then surely the fact that this piece of lazily reasoned hackwork seems destined to be the most quoted of all the Quotable Hitchens is His karmic revenge) that Yael Kohen chooses to open “We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy,” forcing from the beginning what could have been a transcendent and inspiring work of oral history into an oddly defensive crouch. What was almost certainly meant as a topical gambit — the book was born out of an article the author wrote for Marie Claire — feels a bit like reading a novel with a prologue like: “I know you’re probably wondering why you should care about anything I’m about to tell you since I just made it all up in my head, but please let me spend the next 300-plus pages trying to convince you!”

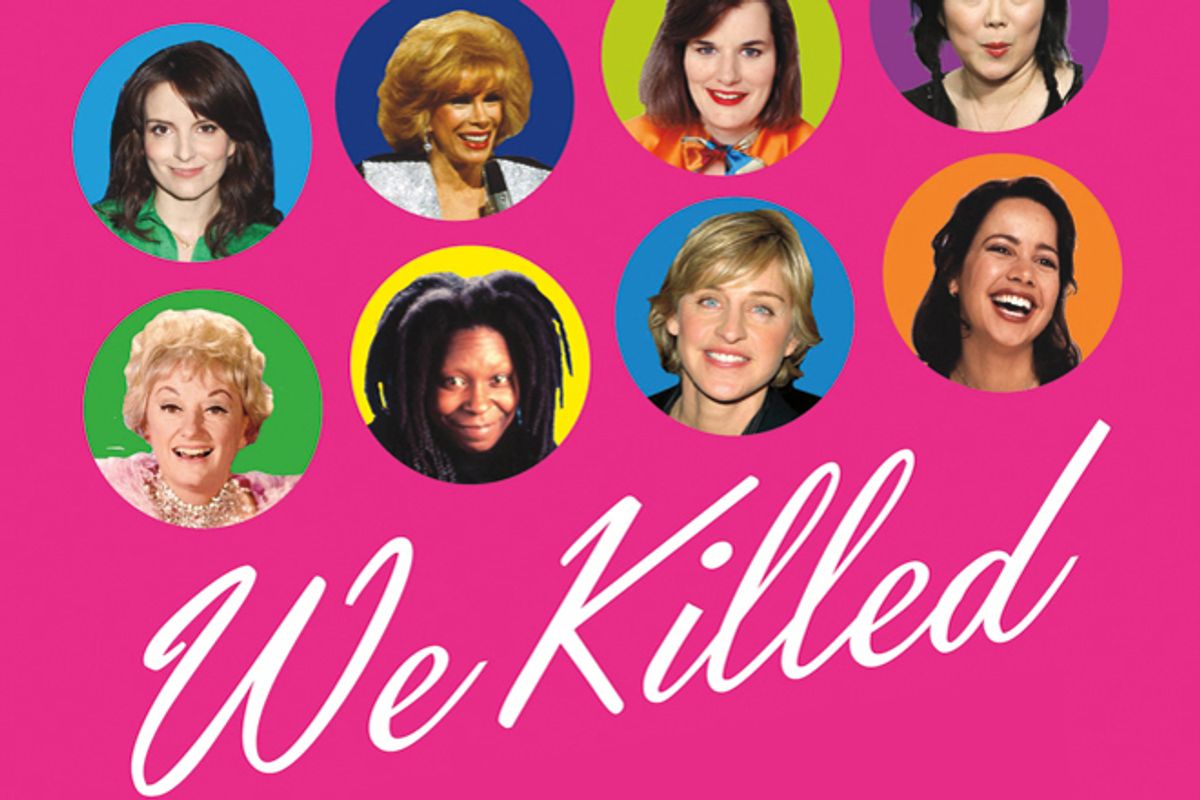

Also strange is Kohen’s emphasis of focusing on her subjects’ relative shortcomings. Under this surely unconscious lens, a fanatically hardworking trailblazer like Joan Rivers is a frustrated actress who failed to take over the desk at “The Tonight Show” and curdled into a bitter insult comic; Carol Burnett, an unchallenging sketch comic; Lily Tomlin, an underground weirdo that nobody knew what to do with. Talents like Sandra Bernhard and Whoopi Goldberg are mostly heard complaining about getting stuck performing in the Belly Room, the all-female performance venue inside L.A’s former Comedy Store (which, in their descriptions of the narrow space and rickety staircase you had to take to get there, sounds like the world’s most hilarious mechitza), but little attention is paid to Goldberg’s subsequent blockbuster film career apart from her briefly noting a sleazy studio executive commenting distastefully on her inherent “unfuckability.” The hilarious Rachel Dratch is encouraged to talk about how affinity for playing unglamorous characters may have hurt her career. Others pontificate — not uncattily, may I add — on how a young Sarah Silverman got stage time because everyone wanted to sleep with her. Why talk to these extraordinary, successful, brilliant women, only to dwell disproportionately on their disappointments? Why treat them as a race apart, or explore their stories mainly relation to men? As Tina Fey, whose voice is notably absent here, said in her memoir “Bossypants” on what she says to young women who come looking to her for advice: “Remember: Don’t be fooled. You’re not in competition with other women. You’re in competition with everyone.”

That’s not to say there’s not some great stuff here. “We Killed” is a well-meaning effort, at times even a noble one. Kohen clearly has a gift for drawing her subjects out: Merrill Markoe’s four-page, stunningly clear-eyed testimony on the rise and fall of her relationship with David Letterman is like a three-act play. Considering how she wound up making her fortune, all the snide comments about the young Kathy Griffin are good for cackle. And the ambitious chronology of the chapters deftly illustrate how the rise of women in comedy mirrored the rise of the women itself, from frustrated housewives to ambitious power-suited baby boomers to sexually frank post-feminists in heels and Spanx. The recurring theme of Johnny Carson’s appalling treatment of female comedians who broke his stringent rules of acceptability speaks a cathartic truth to power, even when the power in question is moldering in the grave.

But for all the dazzling breadth of Kohen’s sources, “We Killed” remains notable for what it leaves out. In her telling, the story of women in American comedy began with Phyllis Diller and Elaine May sometime in the early 1960s. There’s no Fanny Brice or Sophie Tucker; no Dorothy Parker or Frances Marion or Anita Loos; no 1930s screwball heroines that put paid to the former Apatovian notion of the female as eternal straight man. Hollywood scarcely exists at all; the realms of theater and print are totally absent. The name “Nora Ephron” is not mentioned once. Lena Dunham, like robot maids or clothes that change color with your mood, is merely a shadow of a faraway and unknowable future.

Of course, that’s the difficulty of the oral history: You can only talk to people who are alive, or about people who are in living memory, or are willing to talk to you. But if you’re trying to make a definitive case on the potential for hilarity of the double X chromosome, that seems like an awful lot to leave out.

Which brings us to the second problem of writing only about what people want to tell you: It doesn’t leave a lot of room for outside analysis. We hear that Johnny Carson hated female comics and John Belushi refused to perform in anything he knew a woman had written. But neither Kohen nor anybody else tries very hard to explain why. Because ultimately, the question to ask isn’t whether women are funny; the question is why it’s so important to some men that they not be.

Interestingly enough, it’s Christopher Hitchens himself who gives the game away in his essay that started a cottage industry, saying: “Men have to pretend, to themselves as well as to women, that they are not the servants and supplicants. Women, cunning minxes that they are, have to affect not to be the potentates … People in this precarious position do not enjoy being laughed at, and it would not have taken women long to work out that female humor would be the most upsetting of all.” Humor is power. We kill, and something inside them dies.

Shares