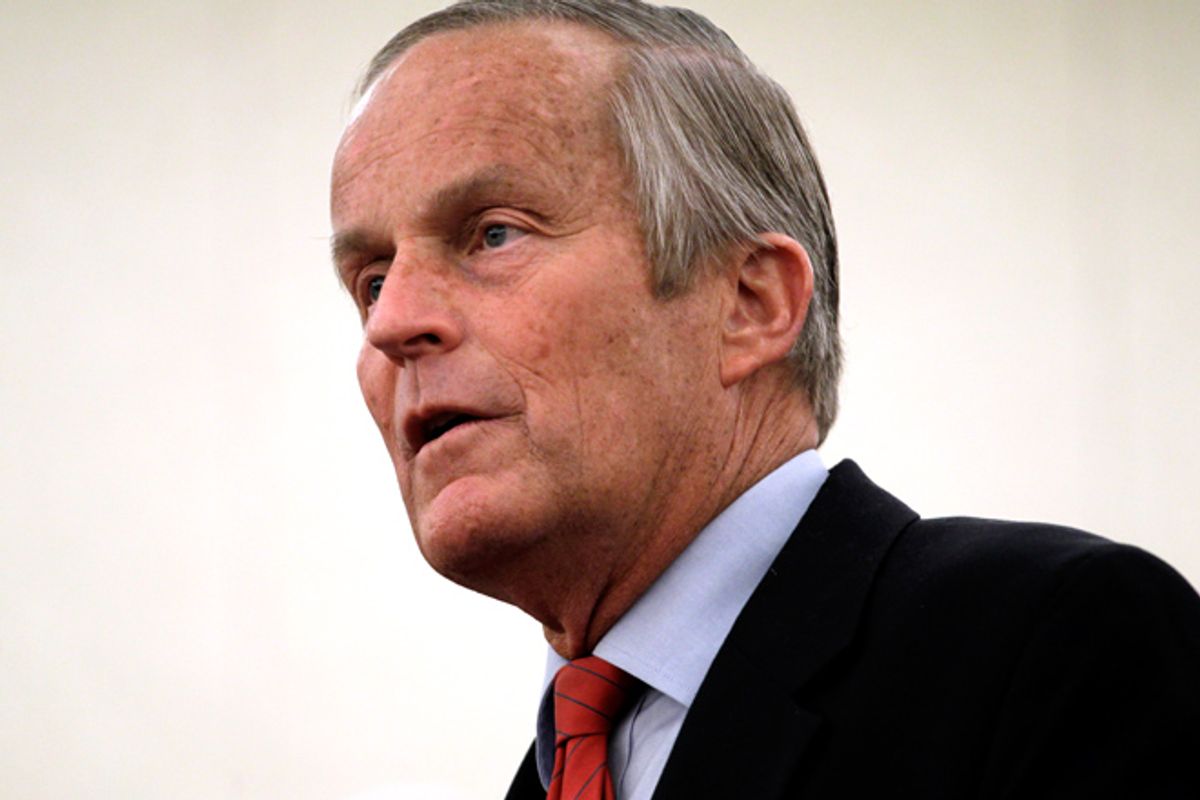

On May 9, 1987, police arrested 30 anti-abortion protesters for blocking the front door of an abortion clinic in St. Louis, Missouri. Among those arrested, according to new information uncovered by the liberal advocacy group People for the American Way, was Rep. Todd Akin, the Missouri Republican Senate candidate best known for saying women can’t get pregnant from “legitimate rape." The arrest ties Akin to one of the most radical anti-abortion activists of the 1990s -- a man later convicted in federal court of threatening abortion doctors -- and, through him, to a right-wing militia group he's long denied having anything to do with.

In August, BuzzFeed uncovered a St. Louis Post-Dispatch article from 2000 reporting that Akin had been invited to speak at a rally of the 1st Missouri Volunteers militia in 1995. He apparently didn't attend the rally, instead sending a laudatory letter to be read to the gathering. According to the paper, a video of the rally “shows a man in camouflage fatigues reading Akin's letter to a crowd of 300.” The letter read, in part: "The local militia can bring a positive influence to our community…. Your patriotism and concern for our state and nation is to be commended.”

When the news became a campaign issue in August, Akin claimed ignorance. “I didn’t know who they were, I didn’t want to have anything to do with them,” he told conservative radio host Laura Ingraham. He said the same thing 12 years ago when an opponent raised the issue in an earlier campaign: "Akin said he was invited to speak to the group but was uncomfortable and turned down the invitation,” the Post-Dispatch reported at the time.

But new information casts doubt on that claim. The full Post-Dispatch story, which was not included in the BuzzFeed story, also reported that “a flier promoting the 1995 event billed Akin as speaker.” Salon obtained the flier (view it here); it advertises a regional conference to teach participants “how to organize Missouri militias.” Akin is listed among the “special guest speakers." How did Akin end up on the flier for the event and why did he write a gushing letter to a group he wanted nothing to do with? Further undermining his account: The only contemporaneous news report, a 1995 article not available online from The Springfield News-Leader, reported that Akin canceled because of "scheduling conflicts,” not discomfort with the militia’s leaders.

Akin’s account that he “didn’t know who they were” becomes even harder to believe in light of the news of his arrest. First, the commander of the now-defunct militia, John Moore, told Salon in August that he had known Akin long before the rally. Moore said the two had met to discuss gun-rights legislation Moore was pushing when Akin was a state representative in the later 1980s: “I’ve known Todd a long time,” he said.

Then there’s Tim Dreste, the milita’s chaplain and captain, whom Akin worked with in the pro-life movement and who, as it turns out, may even have been arrested along with him. Dreste was one of the most infamous anti-abortion activists in the state, known for threatening abortion doctors, leading several invasions of abortion clinics in the late 1980s, and apparently celebrating the murder of abortion doctor David Gunn in 1993.

Dreste headed a group in St. Louis group called Pro-Life Direct Action. Today, we learn that Akin was arrested while participating in a protest with Pro-Life Direct Action. Earlier this month, Akin confirmed to reporters that he had been arrested about 25 years ago while blockading an anti-abortion clinic. PFAW first uncovered a video of Akin discussing the arrest in 2011. Akin confirmed the incident, but refused to provide further details, leading But PFAW to file a public information request with the St. Louis Police Department. Today, the group reported that the department supplied an arrest date of May 9, 1987, the same date that news reports show police had arrested a group of pro-life demonstrators in a protest similar to one Akin described being arrested for.

At the time of Akin’s arrest, Pro-Life Direct Action was headed by a radical anti-abortion activist named John Ryan, who was accused of leading a “reign of terror” against abortion clinics nationwide and who bragged of being arrested almost 350 times. But after it came out later in 1987 that Ryan was having an extramarital affair, Tim Dreste pushed Ryan aside and took over the group. Shortly thereafter, Dreste started an even more radical new group affiliated with Randall Terry’s Operation Rescue called Whole Life Ministries. "Whole Life Ministries soon became the paramount anti-abortion activist group in St. Louis,” journalists James Risen and Judy Thomas wrote in their 1998 book about the pro-life movement, Wrath of Angels.

The next year, Akin addressed Dreste’s new group. In late October of 1988, Whole Life Ministries planned to blockade an abortion clinic as part of a national protest organized by Operation Rescue. Akin rallied Dreste’s troops in a church the night before. “As far as I am concerned, you are the freedom fighters of America... My hat is off to you,'' Akin said, according to a St. Louis Post-Dispatch story. Dreste told the paper that night that he expected to get arrested, explaining, ''We will tell (police) we will obey God's law before we obey man's law.”

In 1990, Akin endorsed a new, more mainstream pro-life initiative called Life Chain. Akin “religiously attended” its events until this year, BuzzFeed reported. Filings on record with the Missouri Secretary of State show that Dreste was the group’s longtime president and registered agent -- the group was registered to his home address -- until 2000.

In 1993, Dreste became "the talk of the anti-abortion and abortion-rights camps when, after the murder in 1993 of Dr. David Gunn in Florida, he carried a sign asking, ‘Do You Feel Under the Gunn?’” as St. Louis Post Dispatch columnist Jo Mannies wrote at the time. That same year, Dreste mounted a long-shot campaign for state representative, which Akin allegedly supported.

When Dreste failed to get into the statehouse, he got involved in the burgeoning right-wing militia movement, helping to found the 1st Missouri Volunteers, also serving as the group’s chaplain and a captain, attracting the attention of the Southern Poverty Law Center. See a program from one of the militia's meetings obtained by Salon here.

Which brings us back to 1995, when the militia invited Akin to speak at a rally and he ended up on a flier as a featured speaker. As Akin tells it, he not only didn't know Moore, who said he knew Akin; nor did he know Dreste, one of the most high-profile anti-abortion activists in the state and someone he appears to have worked with for several years? "That's ridiculous. Saying he didn't know the militia people, that just doesn't stand to reason,” said John Hickey, the former director of Missouri ProVote, a local progressive organization that first obtained video of Akin speaking at the militia in 2000. "St. Louis just isn't that big. It's not New York City... Everybody's going to know each other."

When asked about Akin's relationship with Dreste, Rick Tyler, his colorful spokesperson didn't deny the connection, but merely dismissed its importance in an email as a "20 year-old nothing-to-it bogus story thoroughly reported in Todd's first race for Congress." In fact, while the militia became an issue in Akin's first congressional race, there's little evidence Dreste did.

And Hickey thinks the relationship isn't confined to the past: "Stuff with Dreste isn't just an old curiosity," he told Salon. "There's some kind of ongoing relationship." Indeed, in 2011 video, Akin discusses recently reuniting with people he had been arrested with. "Yesterday I spoke to a group of people who had been in jail with me," he said -- could one of them be Dreste?

Here’s the coda on Dreste: In 1999 he was convicted in federal court for inciting violence against abortion doctors throughout the 1980s and 1990s, which were deemed “true threats" not protected by First Amendment. “It was a federal trial watched around the country,” the Riverfront Times noted in a lengthy profile of the activist from 1999. Dreste and his compatriots were not charged in any of the 40 clinic bombings or seven murders that took place in the U.S. between 1983 and 1999, some of which they were suspected of being involved in, but rather of inciting violence via their websites and other publications under a novel use of federal racketeering laws. “I find that each defendant acted with specific intent and malice in a blatant and illegal communication of true threats to kill, assault or do bodily harm to each of the plaintiffs and with the specific intent to interfere with or intimidate the plaintiffs from engaging in legal medical practices and procedures,” U.S. District Judge court judge Robert E. Jones wrote in his ruling.

That may be even scarier than the militia.

Shares