The United States used to be a country that talked about its dreams with a straight face. The idea that someone born into poverty could work his way up into a better class of life wasn't the setup to a joke; it was, in real terms, doable. Now, we live in an era when social mobility is passé, and everything hinges on a two-tier system: Last year, Detroit announced a two-tier system for new hires while mobile phone companies keep pushing Congress to legalize a two-tier Internet. Santa Monica College, one of the leading community colleges in the U.S., recently proposed a two-tier tuition plan for its most popular courses. There are tolls to get into New York from New Jersey, but not the other way around.

That this class division exists is not shocking. That it's a de facto truth among American politicians whose constituents think "forklift" refers to a movement preceding the salad course – well, that is shocking. While the U.S. has never been a utopia, it used to offer something that the rest of the jaded world did not: the hope, however imperfect, for a better future. It was the land of opportunity, not the land of preexisting conditions. People used to actually brag about leaving behind the Old World, and all of the ingrained prejudices and inflexible lifestyles that it implied.

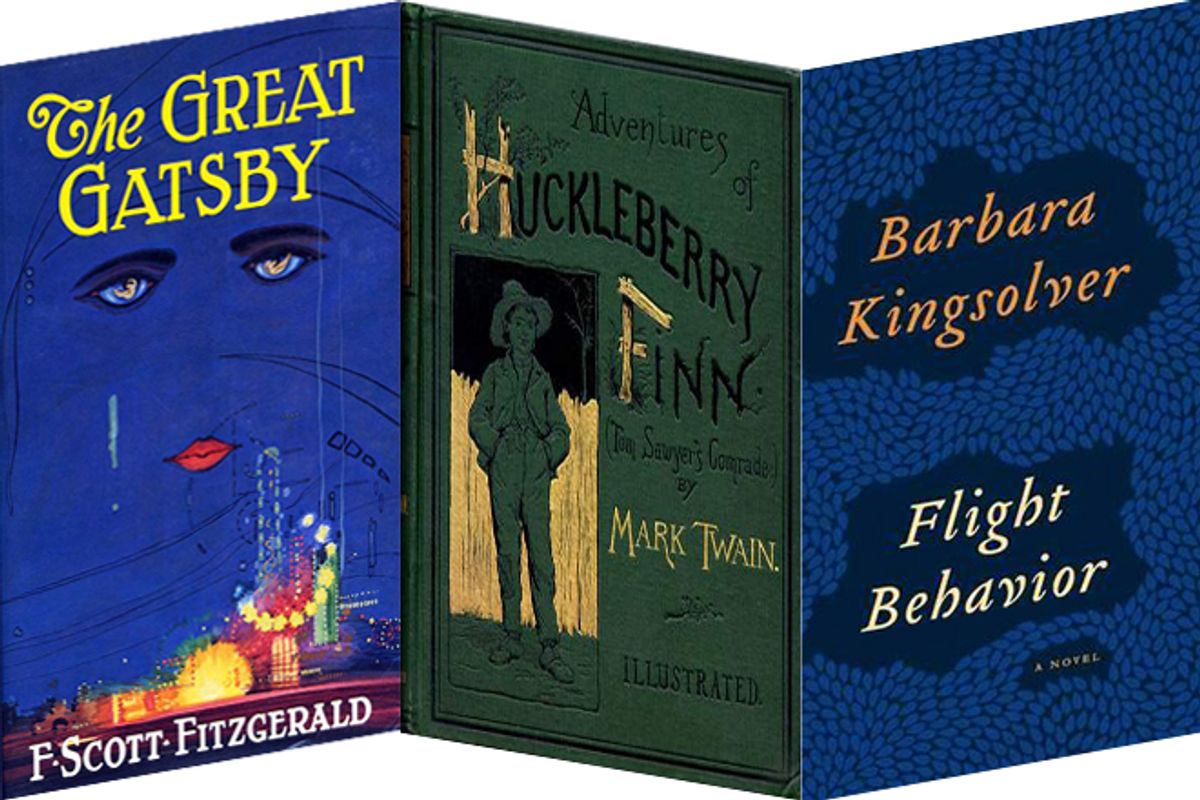

This unfettered American attitude became the basis for an entire genre of literature: The Great American Novel. In its most basic form, the Great American Novel is the chronicle of a journey. The characters set out into a country that is often treacherous, confusing and spiritually ambiguous. But that's the beauty of it; it's up to each person to make of it what they will. Whether it's Gatsby's collision with wealth, Huck Finn's travails across an adolescent country, or even Tyler Durden's drive to start a fight club, there is always the sense that the characters could do anything, go anywhere, become anyone. These novels are not depressing character studies set in an insufferable, boxed-in social system. They are about breaking down boundaries and pursuing dreams and occasionally using mind-altering substances. They're about going broke and reaping a fortune and coming up against prejudice and making something out of yourself. They're about being American, damn it, which is tricky when you're living in a country where even the politicians are cynically rolling their eyes at the notions of "freedom" and "prosperity." Being American used to be defined not by your tax bracket but by your hunger for the unknown. Unfortunately, in an era when economic reality has largely transformed class into a gated community, the Great American Novel is in danger of becoming a quaint fantasy.

"Should we not read books, then?" asks Dellarobia Turnbow, the sheep farmer–turned–activist from Barbara Kingsolver's new novel, "Flight Behavior." It's a question that resonates throughout the rest of the work: Should we give up on our dreams because we don't fit the profile? The book is set in rural Appalachia within a community of people who think climate change is a left-wing hoax and college is for rich kids only. This is a place where basic cable sets the cultural high-water mark. Dellarobia, an Appalachian native who has never boarded an airplane, is barely able to conceive of a life beyond the impoverished constraints of sheep-rearing, at least until a colony of Monarch butterflies decides to winter on her family's property. The butterflies traditionally spend the season in Mexico, but have made an emergency landing in Appalachia due to drastic climate change. Dellarobia first takes in the sight of millions of orange Monarchs fluttering in trees as a personal gift from God. It's not until news of the Monarchs attracts a Harvard-educated, Virgin Islands-born entomologist named Ovid that Dellarobia really begins to feel the chafe of intellectual and economic poverty. Prior to Ovid's arrival, every aspect of her life is framed in terms of a working-class mind-set with diminishing returns. Dellarobia's take on nature: "Whoever was in charge of weather had put a recall on blue and nailed up this mess of dirty white sky like a lousy drywall job." Even holidays are a grim reminder of economic decay: "Christmas tree farms were just proof that every gone thing came back around again, with a worse pay scale." At one point, Dellarobia laments the permanent closing of the local town library due to funding cuts, and the corresponding loss of cultural mobility. "As a child she loved watching the different kinds of adults ... now she moved only among people related by blood or faith, or else, as at the grocery, mute."

Dellarobia, like many people in job-strapped American towns, exists in a world that is only getting smaller. The knockout punch of money and social expectation – in this case, her dependence on her husband's meager wages and the assumption that she will remain unemployed to stay home to raise her children – has flattened her. Thanks to an abbreviated high-school experience, all of her social connections exist within the confines of the town. Aside from television, her exposure to culture is limited to the local papers and the low-grade bitchery of interfamilial politics. She doesn't have leisure time to read, and barely time to think; her every movement is subject to gossip. Despite this, Dellarobia is determined to break through the predefined barriers of her existence. Kingsolver uses the unexpected arrival of the Monarchs, who are struggling to survive in an unfamiliar world, as a catalyst. Soon, Dellarobia is talking back to her controlling mother-in-law and having heated discussions with Ovid the entomologist.

These discussions serve as remarkable portraits of the seemingly unbridgeable gap between two very different worldviews. Ovid's basic convictions about the reality of climate change, of the importance of education, of the rights of women — in other words, the belief system of a class structure that encourages dream fulfillment and exploration – seem ridiculous, if not offensive, to the Limitations-R-Us mentality of the town. "He's not from here, that's the thing," as Dellarobia's husband notes about Ovid, explaining why the entomologist's seemingly wild theories about climate change are met locally with polite skepticism at best. Because of a lack of exposure to the outside world, in this small town truth is judged not by its merit, but rather by how well you know the speaker. In an extended discussion with Ovid about hiring local interns to help with the study of the butterflies, even Dellarobia laughs off the poor education and ingrained cultural attitudes of her home town. "Kids in Feathertown wouldn't know college-bound from a hole in the ground. They don't need it for life around here. College is kind of irrelevant."

This particular passage reads like a death knell for the novel and a free society in general: the idea that higher education is somehow an option, an unnecessary and ego-bloated expense meant only for a pre-selected few. That's the biggest bummer about two-tier systems: They're inherently unequal. Literacy is a learned skill, a way of perceiving the world. But once the divide between the 1 percent and the 99 percent becomes an entrenched class structure, the idea of acquiring certain skills or behaviors "belonging" to the other class becomes ridiculous. If all you're going to do is squeeze sheep udders at dawn, why bother with "The Corrections"? As Kingsolver slyly intimates, in a two-tier system we begin to self-select for failure, based not on our actual merit, but on arbitrary intellectual red-lining.

So, in this age of class war and sharp economic division, is the Great American Novel still relevant? It can be, provided that novelists are able to recapture the spirit of the Great American journey without glossing over the realities of the 21st century. The good news is that novelists like Kingsolver have a particular knack for making us empathize with lives that may bear little resemblance to our own. She makes it clear that people in seemingly dead-end circumstances are not inherently stupid; instead, they live in a culture that encourages them to stay put and shut down. While not everybody can be a Fulbright scholar, her work is a powerful reminder of the basic American credo that no one should be checked off a list at birth. What lifts "Flight Behavior" from an Upton Sinclair–like screed on the brutality of poverty is not just Kingsolver's nuanced and funny prose; it's Dellarobia's awakening to the possibilities around her. Kingsolver isn't content merely to sigh away the problems of the world. At the end of the book, Dellarobia is ready to head out into a country that she recognizes is undergoing dramatic change. There are no guarantees, but Dellarobia is going out there anyway, in search of a better future.

Naturally, it would be foolish to pretend that all it takes to make it in the world is a little starry-eyed gumption. However, as every Great American Novel ultimately testifies, it's vital that we never write ourselves off just because of our perceived class. That spirit of adventure, that embrace of chaos, the refusal to give up on our dreams – oh, hell, being "American" – should never go out of style.

Shares