In 2012, class warfare broke out in American politics. And from the president to key Senate races, the middle class won.

In 2012, class warfare broke out in American politics. And from the president to key Senate races, the middle class won.

When the 2012 campaign began, the lousy economy made President Obama vulnerable. Republicans were favored to take back the Senate, given retirements in conservative states. Republican billionaires — the Koch brothers, Adelson and others — put up big money in the effort to have it all. Instead the president swept to victory, and Democrats gained seats in the Senate and the House.

Many factors contributed. Republicans learned once more the shortcomings of a stale, male, pale, Southern-based party in a nation of diversity. The GOP “legitimate rape” caucus helped give away two Senate seats. But too little attention has been paid to the new emerging reality. This was the first class warfare election of the new Gilded Age — and the middle class won big.

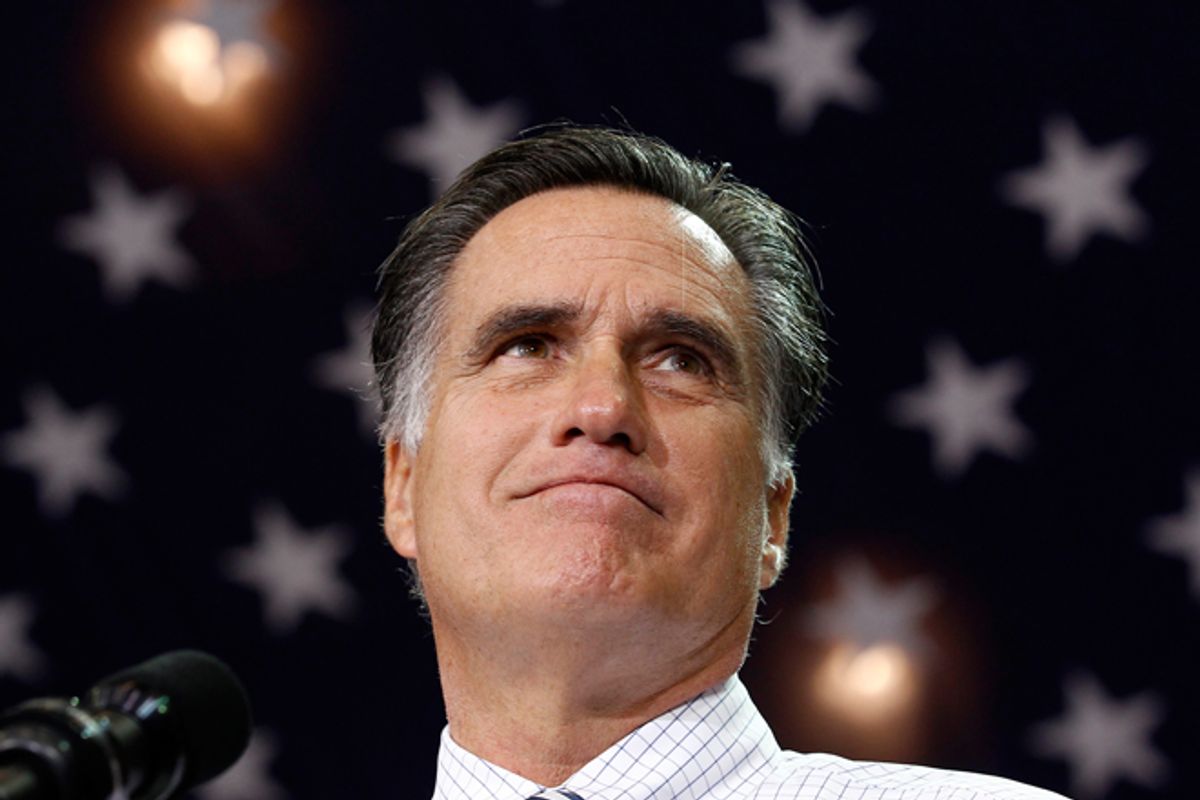

The Republican nominee Mitt Romney was inescapably the candidate of, by and for the 1 percent. He came from the world of finance and carried their agenda. He won the primaries, as Newt Gingrich complained, because he had more billionaires than anyone else. And the rich right were on a wilding, not only funding the Romney campaign, but also filling the coffers of super PACs and their offspring with hundreds of millions of dollars.

The class war, ironically, broke out in the Republican primaries. After Romney’s victory in New Hampshire, Newt Gingrich and Rick Perry savaged Romney as a “vulture capitalist,” the “man from Bain” who profited from breaking up companies, shipping jobs abroad, and leaving a broken carcass behind. Romney’s negatives soared, reaching the highest on record.

And of course Romney reinforced the impression with revealing moments that exposed his yacht club cluelessness: “Corporations are people, my friends”; “I like firing people”; elevators for his cars; the $10,000 bet; $375,000 in speaking fees “isn’t a lot of money”; trying to appeal to Bubba because he knows a lot of NASCAR owners. He secreted his past income tax statements, while the one he revealed exposed a 14 percent tax rate on over $20 million in income, with, in the imitable phrase of former Ohio Governor Ted Strickland, his money “wintering in the Cayman Islands and summering in the Swiss Alps.”

Needless to say, Obama is neither by temperament nor predilection a populist class warrior. But faced with potential defeat, he turned to what works. The depths of the Obama presidency came in the summer of 2011 after the debt ceiling debacle, in which the president was roughed up by Tea Party zealots, and emerged looking weak and ineffective.

Obama came back by deciding to stop seeking back-room compromises with people intent on destroying him and to start making his case. In the fall, he put out the American Jobs Act and stumped across the country demanding that Republicans vote on it. His standing in the polls began to rise. Then Occupy Wall Street exploded, driving America’s extreme inequality and rigged system into the debate. In December, the president embraced the frame: He traveled to Osawatomie, Kansas, revisiting a campaign stop Teddy Roosevelt had made in the first Gilded Age. He indicted the “you’re on your own” economics of Republicans while arguing that “this is a make-or-break moment for the middle class, and for all those who are fighting to get into the middle class.”

In the run-up to the election, the president’s campaign employed two basic strategies. First, the president consolidated his own coalition. He defended contraception and pay equity while his campaign attacked the Republican “war on women.” He reached out to Hispanics by ending the threat of deportation for the Dream kids. He not only ended “don’t ask, don’t tell,” but also moved to embrace gay marriage. Widely described as socially liberal measures, these were also profoundly bread-and-butter concerns. Could women choose when to have children? Could Hispanic children be free to pursue the American dream? Could gay people gain the economic benefits of marriage?

At the same time, the president’s campaign made a risky but remarkably successful decision. Their opinion research showed that painting Romney as a flip-flopper had little traction, but the attacks on vulture capitalism hit home. They decided to spend big money early in such key states as Ohio on a negative ad barrage defining Romney as the heartless vulture capitalist from Bain. Both campaigns believe that Romney never recovered.

But rhetoric and attack ads alone would not have sufficed. In critical Ohio and the Midwest the president was buoyed by one of his most activist — and controversial — interventions: the rescue of the auto industry. Unpopular at the time, opposed by many of his advisors, the auto rescue was risky, painful and messy. But it became the president’s closing argument, for workers knew that he had their backs when they were in trouble.

And when Romney put Rep. Paul Ryan on his ticket, Medicare became central to the debate. Republicans labored to portray themselves as the defenders of Medicare, attacking the president for cutting “$716 billion out of Medicare to pay for a health care plan no one wanted.” But in the Democracy Corps/CAF election night poll, the president had a greater margin on who would do better on Medicare than on any other issue.

And of course, perhaps the most telling bit of class attack was self-inflicted: Romney’s infamous scorn for the “47 percent” of Americans who are “victims” who “don’t take responsibility for their lives.” Many Americans took the comments, uttered in a private setting before deep pocket donors, as revealing Romney’s true feelings. The Obama campaign took full advantage and opened up the largest lead of the campaign going into the first debate.

The president’s listlessness in that debate showed how vulnerable he was. Voters wanted change. They overwhelmingly think the country is on the wrong track. The president’s campaign — from its slogan “forward!” to its closing argument — perversely refused to offer anything than more of the same. As Bill Clinton pleaded at the Democratic Convention, Obama's policies just need more time.

That left Romney an open field to be the candidate of change. But the Bain attacks countered his central argument, “I’m a businessman; I can fix this.” His agenda — a warmed over stew of conservative staples — let Obama argue that we can’t go back to what got us in this mess. The Republican convention, with its disingenuous “we built this” thematic, gave Romney no boost. In the end, voters gave Romney a small edge on who would do better on the economy, but they gave Obama a big edge on who better understands “people like me,” or who will do better restoring the middle class.

Most important, “God, guns and gays” didn’t work this time. The socially divisive tricks that political operatives Lee Atwater and Karl Rove perfected to divide working people and counter populist appeals backfired. The Republican effort to suppress the vote aroused insulted African American and young voters. The harsh anti-immigrant posturing of the Republican primaries drove Hispanics and Asians into Democratic arms.

Class warfare also benefited Democrats in Senate races. Elizabeth Warren, the scourge of Wall Street, used a powerful economic populist message to beat Massachusetts Sen. Scott Brown, a popular incumbent and Tea Party poster boy, running a smart campaign that sought to label her an elitist “professor” who manipulated affirmative action to get ahead.

Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown faced over $30 million in outside negative ads, as Karl Rove made him his leading target. He won as a consistent champion of working people, for the auto rescue, against corporate trade accords, for taking on the big banks. Tammy Baldwin, the only openly gay woman in the Congress, took down the favored former governor of Wisconsin, Tommy Thompson, largely by painting him as a lobbyist for special interests divorced from the concerns of working people. And Heidi Heitkamp produced the biggest upset of all in North Dakota, running an old-time plains populist campaign, for Medicare and Social Security, against corporate trade deals, while savaging her opponent for mistreating tenants in his housing projects.

America’s growing diversity and its increasingly socially liberal attitudes played a big role in this election. But looking back, we are likely to see this as the first of the class warfare elections of our new Gilded Age of extreme inequality. A besieged middle class is increasingly aware that the rules are rigged against them. They are increasingly skeptical of politicians and parties, and believe — not incorrectly — that Washington is largely bought and sold. But they are looking for champions.

For years, conservatives in both parties have warned against class warfare. Americans, we’re told, don’t like that divisiveness. They see it as the politics of envy. Inequality should, as Mitt Romney said, only be talked about in back rooms.

Nonsense.

More and more of our elections going forward will feature class warfare — only this time with the middle class fighting back. And candidates are going to have to be clear about which side they are on. Politicians in both parties are now hearing CEOs telling them that it is time for a deal that cuts Medicare and Social Security benefits in exchange for tax reform that lowers rates and closes loopholes. Before they take that advice, they might just want to look over their shoulders at what will be coming at them.

Shares