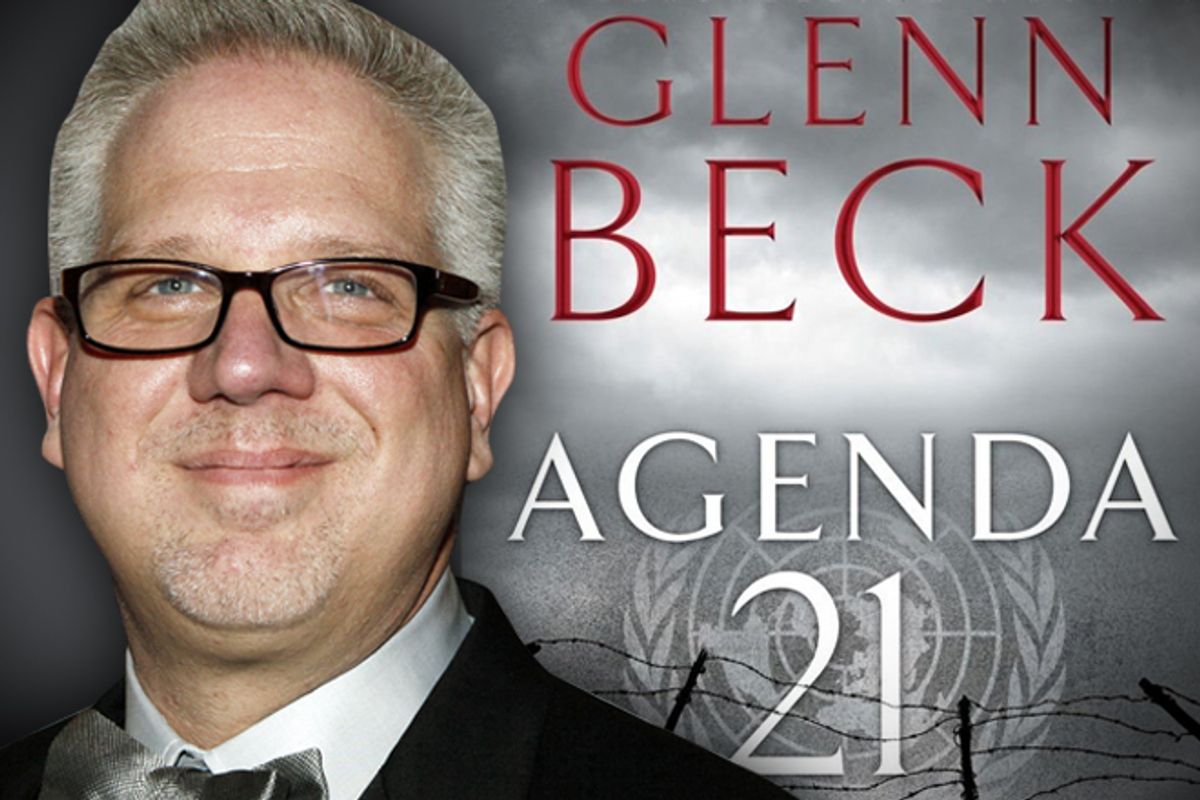

Two weeks ago I discovered, to my surprise, that I had line-edited an early draft of Glenn Beck’s new novel, "Agenda 21." Glenn Beck! At the time I was working on it, the manuscript belonged to its actual author, a woman named Harriet Parke, who lives a few minutes from my aunt. But a year and a few lawyers later, Glenn Beck purchased the right to call himself its creator, and Ms. Parke agreed to be presented as a ghostwriter.

I would be proud to have my name in the acknowledgments of Ms. Parke’s novel. But given that it is printed inside a book bearing Glenn Beck’s name, the work I did is now deeply at odds with who I am as an editor. "Agenda 21" is going out into the world on Tuesday, Nov. 20, as something decidedly different from the novel I edited. Yes, the story is the same. So are the concepts, the characters and the writing. But the name in the byline — that changes the book’s intent. It changes everything.

If you're not an urban planner, here’s a crash course on the novel’s eponymous United Nations Agenda 21. It’s a 40-chapter behemoth written in 1993. It lays out non-binding guidelines for promoting economic growth, environmental protection and social equality. Basically, it is a recipe for living within our means today, so that we do not pass along to our children a degraded economy, environment and society. It addresses topics as various as toxic waste, biotechnology, conservation and green transportation, all with the goal of helping poor countries develop economies — in large part, by encouraging wealthy countries to dial back in sensible ways on their consumption of resources.

Today, city and regional planners support the concepts that underpin Agenda 21, because they translate the big picture to local efforts to save people time and money. In other words, think globally, act regionally. After all, the planning profession is about supporting a community’s efforts to collaboratively make the best of change — such as whether your community is growing or shrinking, or becoming more rural, suburban or urban. Change is inevitable: Brookings reports that “our population exceeded 300 million in 2006, and we are on track to hit 350 million in the next 15 years.” And that “America will probably be older, more diverse, more urban — and less equal” than we are today.

Planners help communities find common-sense, constructive ways of using limited resources wisely. It looks for ways to make transportation inexpensive, keep energy plentiful, and help towns and cities avoid the kind of bad economic decisions that lead to eyesores like, say, a half-deserted strip mall anchored to an abandoned Wal-Mart. Thanks to zoning, for instance, which was created in the 1920s to protect property values, no one can come in and inappropriately construct a landfill or a steel mill next to your house.

Glenn Beck and fellow pundits hate Agenda 21, however, because they interpret a few lines from chapter four out of context. Their scare tactic is to say it’s the narrow end of a wedge that will insert global UN authority over American towns and cities, allow the government to confiscate private land, reallocate resources by force, and evict people from their single-family homes. Never mind that the law of the land begins with the United States Constitution and that our relationship with the UN can hardly be described as lockstep. Moreover, the United States has no land use laws at the federal level, whatsoever. All land use decision-making authority in the United States lies with the states, who delegate authority to local governments. Relatively speaking, the United States has some of the strictest protections for private property in the world.

Agenda 21 is simply a non-binding, unenforceable menu of guidelines that exists to help any town or city that signs on to it. But when removed from all sensible context and cast forward into a dystopian future, Agenda 21 becomes the novel "Agenda 21," which tells the story of a post-American settlement where people are forced to ride bikes and walk on treadmills to generate electricity, told whom to marry, raised in communal kibbutz-like nurseries, and forced to swear allegiance to a scary green one-world socialist entity.

My job is to edit stories, not the author's sensibility. Sometimes I edit a manuscript whose politics or sense of the human condition doesn’t agree with my own. That was the case with Ms. Parke’s draft of "Agenda 21," which contains a caricature of some things I find highly inoffensive, such as bicycles and feeding squirrels. I am OK with that, personally and professionally, because novels are meant to be read as fiction, as a form of complex entertainment. There is joy, too, in discovering and thinking about the ideas that underpin the plot. And besides, if everybody agreed, we’d live in a dully conformist world indeed. Think of something like Orwell’s London in "1984," which contains a vision of socialism whose simplified specter still haunts berserk right-wing pundits like … well, like Glenn Beck.

Furthermore — and I must speculate here — the novel’s actual author, a retired nurse in western Pennsylvania, has gained income and national recognition for years of hard work. I can’t argue with that, either. We writers all want that. The only interesting thing here is that it comes with the sacrifice of her authorship: Her name appears as a “ghostwriter” in small letters on the cover. But she conceived of and wrote the book herself, and I respect the humility it must take to partially efface one’s name from one’s own work. In an ideal world, all writers would write anonymously.

If the book had been published under Ms. Parke’s name alone, it would remain an entertaining dystopian novel. The writing is capable, the story compelling, and most of its values are to be respected — family, localness, and a good education in history (Beck, and his publishing house, ought to take note of that, by the way). It would be marketed and sold to readers of speculative fiction, which are typically a brainy crowd. Maybe some among them would hold it up as a negative vision of a radical environmental agenda run amok, albeit in a world without Exxon Mobil or Wal-Mart — in fact, one without any wealthy corporations at all, who historically pitch their vast financial resources against environmental regulations.

But mostly, we’d just read it for the story. That’s how I read it one year ago, and I enjoyed it. But why publish the novel under Beck’s name? What would the book have lost if his publishing company, Mercury Ink, had simply let Ms. Parke call the novel her own? The answer, I think, is that it needs Beck’s franchise in order to succeed in a purpose beyond entertainment.

Publishing "Agenda 21" under Glenn Beck’s name transforms it, at least temporarily. Glenn Beck is more than just the nice guy whose publishing house is bringing Ms. Parke’s work to a national audience. He’s also a professional ideologue whose establishment confers the full force of its intellectually and morally irresponsible franchise on a novel that distorts the truth about Agenda 21, which is doing good work in the world. Glenn Beck is not writing as an artist, bound by the conventions of his art, plying his craft on the willing human imagination. Hell, he’s not writing at all. He is a brand, with a budget, and with an agenda of his own. Ultimately, by assigning his brand to the novel "Agenda 21," Beck turns a form of entertainment into a political lie, a tool for politicizing people.

On its own, "Agenda 21" should not work this way: just like Margaret Atwood’s "The Handmaid’s Tale" does not drive women to the polls to keep religion out of politics, nor "The Hunger Games" motivate us to stop seeing war as a form of entertainment, nor "One Hundred Years of Solitude" give a corporation pause before plundering resources from poorer countries. If people show up en masse to vote for or against these things, it is not because spokespeople from NARAL or the NEA or the Union of Concerned Scientists pushed these novels on national TV; it’s because people are responding to something provable and real right now.

The novel "Agenda 21" was inspired by Beck’s entreaty to his viewers to “do your own research.” Well, fine — if you read a single paragraph of a 40-chapter political tract, you can spin it all kinds of ways and call it “research.” Beck does as much on his show, and I worry that Beck’s many readers will get the wrong idea about the UN Agenda 21. In principle, it is an important part of city and regional planners’ work, which involves making sure that people can access things they need: food, education, doctors’ offices, stores. It’s about making sure those things are even there when you need them. It’s about helping people enjoy freedom and mobility, even if they are too poor or too old or too young to have a car. Or just don’t want one. It’s about the preservation of localness and sense of place instead of generic-ization, and about maintaining a familiar, comfortable way of life as our population expands from 300 million to over 400 million in my lifetime.

If, like me, you feel concerned about the inevitable population growth, decreased availability of clean water and resources, aging national infrastructure, and upward-trending global temperatures, you might take heart to know that city and regional planners are numerous, bright, well-educated people who devote their careers to finding ways to helping the rest of us enjoy a long-term high standard of living. Or, you can empower obstructionists who make the panicked hoarding of fuel and canned goods seem like the only long-term planning that matters.

There is a precedent for successful social fiction. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s "Uncle Tom’s Cabin" focused public sentiment against slavery because its unstinting realism humanized a gross injustice that was already tinder in the national furnace. For the same reason, Upton Sinclair’s "The Jungle" spurred labor reforms, though arguably it could have been more successful, sooner, if it hadn’t slathered so much socialist propaganda onto a realistic portrayal of factory life.

Usually, though, preachy fiction is a brittle failure. I think of an interesting but flimsy environmental novel like Daniel Quinn’s "Ishmael," whose political message overtakes the story. Gore Vidal’s fiction suffers for the same reason. I do respect the writer who champions the underdog — the working poor, the immigrant, the father of hungry children, the ambitious teen who is under-served by an opportunist or parochial education system. Less so, the writer whose vision empowers an avaricious establishment, or obstructs meaningful adaptation to our changing environment. Yet when I suspend my disbelief to read speculative fiction, finding myself preached to at all is an annoying betrayal.

Where that creative betrayal becomes shrill, however, is in the mouth of an ideologue. As a genre, speculative fiction keeps one eye on politics, but its goal is not to preach. It’s to make up an entertaining version of reality — an augmentation of social truth, which is not the truth itself. A novel’s vision can scare us, inspire us, affirm our emotions, and articulate our fears. It shouldn’t, however, serve as a primary political agenda any more than Paul Ryan should be waving "Atlas Shrugged" around on the House floor. In the same way, "Agenda 21" is being delivered as propaganda, and by buying the right to call himself its author, Glenn Beck is diminishing a work of fiction to nothing more than a cheap appeal directed at people who will believe anything.

Shares