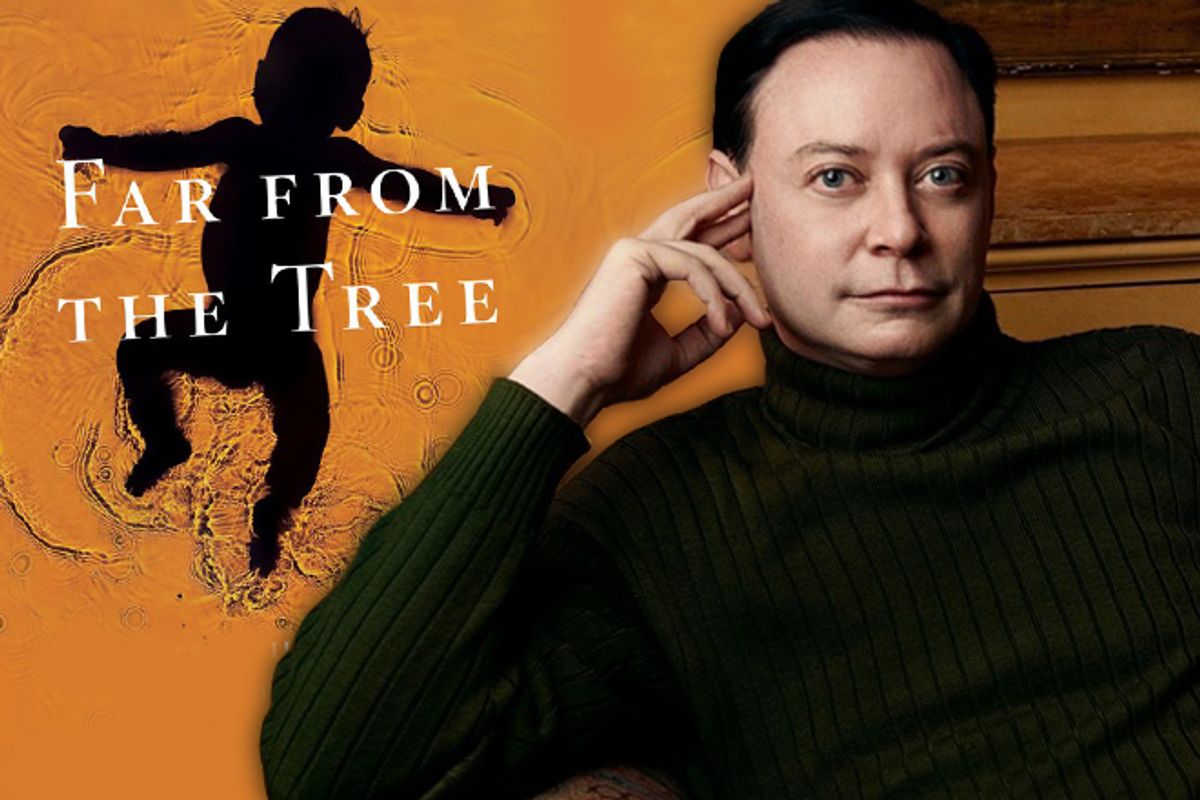

The chapters in Andrew Solomon's staggering and forever eye-opening "Far From The Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity" include a litany of difference and pain that few parents would wish upon their children -- or upon themselves as mothers and fathers: Deaf, Dwarfs, Down Syndrome, Autism, Schizophrenia, Rape, Crime.

But ordinary families, Solomon writes, find a way to love the most extraordinary children -- those conceived in rape, those with disfiguring illnesses, those who become criminals. No matter what, these kids are still theirs. Solomon's project is about difference, yes, but also our ability to love. And while his definition of extraordinary is sometimes jarring -- it is broad enough to include the transgendered, the autistic, children conceived in rape and also Columbine killer Dylan Klebold -- they are connected, for Solomon, by parents who found themselves with children very different than they expected. Which is to say, children very different from themselves.

"Having anticipated the onward march of our selfish genes, many of us are unprepared for children who present unfamiliar needs. Parenthood abruptly catapults into a permanent relationship with a stranger, and the more alien the stranger, the stronger the whiff of negativity," he writes. "Children whose defining quality annihilates (our) fantasy of immortality are a particular insult; we must love them for themselves, and not for the best of ourselves in them, and that is a great deal harder to do."

The triumph of Solomon's book is that it becomes an argument about what it really means to celebrate difference and diversity, not merely in name or in theory, but in day-to-day life. And it is about learning that there can be tremendous happiness in that process. Solomon shares hundreds of incredibly moving stories of unexpected challenges met with -- and by parents who must battle their desire to gaze at a newborn and see themselves -- previously unimaginable empathy and generosity. Not all of these experiences are pleasurable or even overcome, but all of them offer lessons, all require people to stretch their boundaries and face their prejudices. And it's in that way that the entire culture -- not just individual families - moves forward.

You will probably find yourself wiping away tears. You will find yourself underlining lines of breathtaking insight on nearly every other page. You might find yourself angry over the way Solomon equates or compares very different challenges. But it's impossible to read "Far From The Tree" without testing the limits of your own empathy. Forget what Jesus would do. What would you do?

We talked to Solomon earlier this week from Toronto.

Each chapter in your book presents a very unique kind of difference. What ties them together, and should we tie them together?

All of these people that I’ve been talking to are dealing with very specific kinds of difference and feeling, in most instances, isolated by the condition they had. There aren’t that many people with schizophrenia; there aren’t that many people with dwarfism; there aren’t that many people in any of these categories. And I found out that there is so much that their experiences have in common -- that process of accommodating, accepting, loving, even celebrating a child who had a marked difference from what the parents had in mind was really quite consistent from group to group. It didn’t really matter whether we were looking at what the child did, as we were in the crime chapter; or how the child was born, in the Down Syndrome chapter. That was consistent. And it had a lot in common, in my view, with the experience I had negotiated as the gay child of straight parents. And so I think that sense of difference is actually something that almost everyone has in common, rather than something that isolates people. I didn’t know that’s what I was working on in the beginning.

The other theme that runs through the book is the very complex relationship between illness and identity -- that what some people see as something which needs to be cured is, to others, a defining characteristic and community. And that the culture shifts, and sometimes what was once viewed as an illness, becomes seen as identity.

Right. When, I was born being gay was an illness and in my adult life it’s an identity. And I don’t know which of the categories I’ve written about will make that switch to what degree at what time. There’s no crystal ball. But I do have the feeling, very strongly, that these are fluid categories, and what’s true right now is not the same as what’s going to be true in 10 years or 20 years. And, I just think that people are sometimes naive about the prejudices and positions and attitudes of their time, and don’t realize how much all of these things are subject to flux.

And parents, amazingly, are sometimes naive and wrong about their own attitudes and their own capacity to love. They might not have expected to deal with these situations as parents -- as one mother says, "If someone has said to me, 'Betty, how'd you like to give birth to a lesbian dwarf?,' I don't think I would have checked that box." But the best ones find a way to value the experience themselves. Did you think you were going to be doing a study of unhappy families, all unhappy in their own ways.

I was frankly kind of amazed. When I started the book I thought, gee, I’m looking at all these difficult situations and I think I’ll be looking at a lot of miserable families. And I looked at a lot of families where there was a lot of pain, and I’m not by any means saying: Oh poor you, parents who don't have a child with Down Syndrome, you’re really missing out. It’s difficult -- it’s not what anyone would run out and choose for themselves and for their children.

So, quite simply, how do the parents do it?

I was surprised at how deep the attachments were, and how families kept saying to me, “I wouldn’t want to change my child; I wouldn’t want to give up this child; I don’t wish that I’d had a different child.” And I finally came to that point of thinking, okay, that’s how we all feel about our children. I think my children are pretty fantastic but I would have to be honest and admit that they have some flaws. I don’t particularly want to exchange them for other children who don’t have their flaws. If that’s true for me and my children, with their somewhat less dramatic challenges than the people I was writing about, then why wouldn’t it be true for other people and for their relationship with those children?

Let me jump back for a second: How does it happen that one of the these topics you write makes that cultural shift, from seeming like it is an illness, to becoming an identity. And would you explain what you call horizontal and vertical identities and how that's connected?

My work on the deaf (for the New York Times magazine) was really my taking-off point. It had never occurred to me at the time that there was such a thing as deaf culture. The whole thing was a completely foreign idea to me. I was quite shocked when I’d got out among deaf people and they didn’t experience themselves primarily as lacking hearing; they experienced themselves primarily as having membership in this culture by having sign language. Now some of them liked that culture, and were thrilled to be part of it, and some of them were less enthusiastic about it. But they all had a sense that they were part of something cultural.

I thought, okay. Many of them felt that it was their culture and they liked it. And one does like one’s culture, by and large, by some degree or measure. So would my life have been easier if I weren’t gay? Yeah, it would have been in a lot of ways. And there was a period in my life when I might have wished to make a switch. Now, it’s not that I think that being gay is the most amazing, wonderful thing in the world, but I have a husband; I have a life; I have friends who I’ve met through this. It’s who I am. ...

And I was thinking wow, who knew? Well, I guess a lot of people knew -- but I didn’t. I thought if the thing that I called an illness is experienced by many of the people who are living it as an identity, and if I myself had the experience of having my way of being called an illness and have come to think of it as an identity, then what else can fall into these categories? My feeling in the end is that everything can be described as both.

If you look at the language of illness you can use it to describe race -- you could experience race as an illness. You can experience income level, at many different levels, as a form of illness. You can experience age as an illness. I mean, it’s all got an illness component.

What do you mean by that?

An illness component meaning, essentially, a component of it appearing to be socially undesirable in certain contexts, and handicapping and preventing someone from doing things they might conceivably want to do. And I thought you can also experience everything as an identity. Obviously the things I just listed are generally considered identities and I’ve described them as illnesses.

So a vertical identity is whatever is passed down generationally. And horizontal identity is what happens when a child is different from his family.

You argue that vertical identities are valued -- and the horizontal identities are often the ones that parents initially try to change.

Yes, anything that is passed down generationally, almost without exception, gets valued. If your children have Huntington’s disease and you do too, then there’s no question in everyone’s mind that it is a terrible illness -- you’re likely to die young from it and it would be great to find a way to cure it.

You could say that it’s as much of a disadvantage in many parts of America to be black as it is to be gay. But you don’t have black parents bringing up their children to be not black. But you do have all of these straight parents wishing they could make their children not gay, because there is a natural tendency to think whatever your dealing with, whatever your experience is, whatever your way of being happy, is really the primary, best, and the only way of being happy. And that belief caused those parents to attempt to rectify these differences in their children. The children discover, actually, lots of people have the same condition I do; I’m part of the culture. It’s a vibrant culture. And the parents then have to reconcile themselves to the culture that their children inhabit, which is completely foreign to them.

Did you find that this was a result of parents wanting their kids to be more like themselves, or parents hoping to keep their kids from experiencing the pain of difference?

You know, I think it’s both. I think a lot of parents want to save their kids from the pain of difference. I think a lot of the parents who want to do that haven’t investigated very thoroughly what the nature of this particular difference is, or what the community is within which their child might find family.

If you’re Latino and live in a Latino neighborhood and you have a lot of Latino friends and have a Latino identity, you can sort of see that. If you have a child whose deaf, and you’ve never heard of deaf culture and suddenly you are handed this child, where do you find this community in which your child will be happy? Why would you even know that it exists?

Part of my purpose in writing the book is to say not only the communities described in these 10 chapters, but many other communities are out there, and for people to be awake to them. But I think that there’s both the question of worrying about your child and what it would be like for your child to have the identity of a deaf person. And there’s the question about how you feel about having the identity of the parent of a deaf child, because who your children are takes up a lot of who you are.

And then there’s the role of science. Scientific and medical advances mean we can screen for some of the genetic mutations which might suggest Downs, or that we have cochlear implants for the deaf. These are controversial within their communities. Where should science and medicine draw the line when it comes to "curing" what some people see as identities and communities?

You know, I think that the line about what should be cured and what shouldn’t be cured -- I think it’s a very personal question. Science will move forward, we will be able to understand more and more about these conditions, and will be able to prevent them or, as you point out, be able to terminate pregnancies that would entail a lot of these conditions.

And I feel torn because I think on the one hand, if I had a child who was deaf, I would get that child a cochlear implant. I would get the child a cochlear implant because communication is one of the most important thing between parents and children, and I would want to be able to communicate with my own child. And I would do it because I think the access of the cochlear implant means that, that beautiful world that I’ve just described to you, and that I’ve chronicled in the book, is a shrinking place.

So, that’s probably what I’d do for my child. Having said that, the idea of having the whole deaf culture disappear from the face of the world seems very sad to me. Now, cultures disappear all the time. It’s not that I think that we should stop science in order to free the world from this moment because those cultures are so wonderful, it’s just that I think we should notice what we’re doing. And we should look at the ways at what is being lost as we make this progress, and think through its ramifications.

The ramifications in many cases are fairly clear: The parents choose to end the pregnancy.

I’m all for science and I’m all for people having children in the way that they want to. You know, if someone is up for having a severely disabled child, and she’s able to cope with it, that’s great. If someone else feels that’s it’s just more than they could ever possibly handle they shouldn’t have to do it. I feel like it’s up for people to decide what they can deal with in their children. My objective is only to say: let me help you be more informed as you make the decision. I would never want the book to be taken to imply that people are morally obligated to have children who fit these descriptions.

There's a harrowing chapter in the book about rape, about women who decided to give birth to, and raise, children who were conceived during a rape. They talk about how their kids might have their rapist's laugh or his eyes, about how the child can remind them of one of the worst things they've ever had to endure. How do they find the capacity to love these children and love themselves?

I think that there’s frequently a tension between the idea of the child, the child as this concrete representation of what has happened to them, and the person who the child actually is. So the mothers find themselves thinking not "I hate this child because he’s mean and terrible and ugly and brutal, but this child is a reminder of someone else who was terrible and brutal to me, and prevents me from escaping my own memory."

So why do they do it?

I have people who have said to me that if I had to carry a child after becoming pregnant in rape I would’ve killed myself, I couldn’t dare have such a child. There were other people who said having this child actually meant that something of beauty and value came out of the experience of being raped. I was very struck by the possibilities that there are for growth over time. I think rape is among the traumas from which one is never fully and entirely recovered -- it’s always a partial recovery at best from that experience.

Did the women you spoke with find that the child helped them recover, or made it impossible to ever put that day behind them?

I think that there is the women who said to me, when I asked whether she thought about the people who had brutally raped her, effectively destroyed all of her ambitions and done her enormous damage when she was 16. And I said to her do you think of the rapist now? And she said, well, I think of him with pity. And I said why with pity? And she said because he has a beautiful daughter and two beautiful grandchildren, and he doesn’t know that and I do. And so, as it turns out, I’m the lucky one.

But it had taken her a long time to get to such a point. It was a long process of struggle. And I would never want anything I’ve written to be taken to mean either A: that everyone should love their rape children and they should go ahead and have them. Or B: once you’ve realized how much you love your child the whole things becomes easy. You know, it isn’t easy. There are some people for whom the best means of recovery is not to have the child, and there are others for whom the best way forward seems to be to have the child.

The question of choice and abortion rights hangs over so many of these chapters. It's often the first decision these parents have to make: Should we have this baby? And in several chapters, there appear to be ties between pro-life groups and the organizations trying to protect the cultures or rights of these extraordinary children. They'd be natural allies. How close did you find these ties to be?

There are a lot of people in the disability community, in the community of children of rape, in a number of these communities, who refer to themselves as having survived the threat of abortion. They announce it as it were an athletic triumph. And, they say if people would have had an abortion I would have never been born.

My own view is that I’m glad to be here, but if I hadn’t made it to the earth I wouldn’t be here to mind not having made it. It’s seems to me to be a kind of complicated stance to take. And, as I said, I’m a great believer in -- I mean, I’m an abortion libertarian -- that everyone should have unfettered access in the decision to have a child or not have a child. It’s up to the person who is carrying the pregnancy, and perhaps the other person involved in creating it.

Having said all of that, I also think there are a lot of people who terminate pregnancies with children who they might have loved if the children had actually been born. I would never want anything I say to be construed as pro-life. But I do feel that these decisions tend to be made in a kind of ignorance because the conditions that I’ve written about have been so brutally stigmatized. Some people don’t know anything other than "My child has a disease. It’s terrible." And I just thought, well, there is more information out there that you might want to look at as you make your decision.

Would you make a decision like this in a different way now?

I'm not suggesting that everyone should -- or even that I would necessarily -- carry through a pregnancy once I have such a tough diagnosis. But I certainly wouldn’t be able to terminate it in the definitive “Oh God, why would anyone want to do that” way that I believed at some point in the past. I think that’s really been the shift. I think the onward march of society should be to make it more open, and more embracing. And the onward march of medicine should be to make it easier and easier to deal with conditions that are painful and difficult. And I just think sometimes those intersect with a loud bang. That can be a problem, but I hope we will have more progress on both fronts. I think it would be great if in 50 years you could find out lots more about the conditions your child is going to have -- and if we lived in a society that is so tolerant that many things that might now lead to abortion would then be seen as part of human variance.

Opening up possibilities is what I was interested in. I was interested in the context of the book in the idea that I was looking at all of these children who are considered, by many people, as hard to love. You know, (parents who say), I don’t know if I could love someone with Down Syndrome; I really want to have someone intelligent to talk to. I don’t know whether I could really love someone who is so profoundly disabled. I don’t know if I could love someone who is autistic and therefore doesn’t interact with me in the emotional vocabulary that I function in. And I thought, okay, if you’re looking at people who are difficult to love, well, in the case of a child born after a rape, then how difficult is it to love someone who is the product of the most hideous trauma that you have ever endured? And I found that, as in the other cases, there were a surprisingly large number of people who rose to the occasion.

The pain and humanity of the Klebold family, whose son, Dylan, was one of the shooters at Columbine, is almost unbearable. As you write, "They are the victims of the terrifying, profound unknowability of even the most intimate human relationship." And they are parents who still love and remember and mourn their son, despite the horror of his actions. They come off as caring, terrific people and parents -- and yet somehow they had no idea of the evil inside their own house, and that guilt will never go away. Do you understand what happened at Columbine more or less, having gotten to know them?

I thought that when I went out there, if I really get to know these people I’m going to figure out why this happened and I’ll understand what was going on. And in a way, if that had been the case it would have been reassuring because I could then think: Oh, I see this kind of person and they did these things wrong and that’s why their child ended up that way. And I will not do those things wrong and my child will not end up that way. But I have to say I’ve spent hundreds and hundreds of hours with them and I’ve known them for seven years now and they’re among the nicest people I’ve ever met. And I happen to be very fond of my parents, but if I weren’t I would have been perfectly happy to be brought up by them.

I think that what they had with Dylan was this sort of mental state that was sort of exacerbated by his contact with Eric (Harris), who was the other person in the process. He was unknowable, he was unknown, and there’s nothing in the circle of their family that would have caused this. Indeed, I actually thought that his mother was a lot more morally engaged and admirable and kind than most people I encounter in the course of my day to day life. So the more time I spent with them the more mystifying it was.

You don't think there's anything they could have done. So if empathetic, kind parents can still raise someone who becomes a killer, what kind of influence can a parent have?

For years they said that homosexuality was caused by overbearing mothers. And that autism is caused by "refrigerator mothers." Schizophrenia was a result of the parents unconsciously wish the child not exist. If you go back a couple of hundred years we said that dwarfism was caused by the unexpressed lascivious, obscene longings of the mother. So there’s been all of this stuff that’s been: blame the parents, blame the parents, blame the parents. We have to step back from that. It's sort of barbaric and ridiculous.

Obviously, parents don’t cause their children to develop schizophrenia, by rejecting them. Schizophrenia is a terrible terrible thing, but that’s not where it comes from. But we do still have that point of view, that somehow it’s all just the parents. My experience is that there is no question that parental behavior can exacerbate criminal tendencies, or enable them. So children who are terribly abused and neglected are much more likely to end up as criminals than children who are brought up in a loving household.

Having said that, there are a lot of people brought up in loving households and who just go this way. And in my view, it appeared to me that criminality was just as much of an illness as anything else that I’ve written about. But it’s unfair and even sometimes cruel to keep blaming parents all the time. And the Klebolds are the epitome of that. As I say, they are lovely people, it’s a lovely household, they brought up a child with enormous love. Then he did something unbelievably horrifying. But that’s sometimes the way it goes.

We've all kept secrets from parents and the people closest to us. So for people to believe it isn't possible for the parents not to know...

Right! People kept saying, "but how could the parents not have known?" And I thought, well, I kept a pretty good secret from my parents about being gay for quite a long time. We all have these various things that we do, you know, that our parents don’t know about.

You undertook this project partially in the interest of examining you own relationship with your parents and trying to work through your teenage relationship with them. And as you were writing, you had children of your own, and married a man who also has children. So how did you come out of this book as a different father and a different son.

I think as a son that I have for a long time complained that my parents didn’t adequately love me when they found out that I was gay. What I felt after doing the book was that they had actually always loved me; what they didn’t do for a while was accept me. Then they worked it through, and they did accept me. And that actually dealing with a child who is different is very difficult. All of the kids who I’ve met, and all of the families who I’ve met, have had to go through an adjustment period. And I got the perspective looking at all of it to think my parents actually did a really, pretty, good job, all things considered. They adjusted reasonably well, they did it reasonably quickly, and my youthful idea that it shouldn’t entail any degree of struggle whatsoever was psychologically naive. So I kind of got over the annoyance of my parents that had afflicted me.

But as a father, I’ve had people say to me: “God, you’ve decided to have children while you’re working on this book about everything that can go wrong.” And I kept saying to people it’s not actually a book about everything that can go wrong. It’s a book about how resilient families are, and how profoundly possible it is to love children even in circumstances in which things have gone wrong. And that seemed to me to be a very different book. And to pose a very different sort of question.

So I think I felt confident that I would love whatever child I have -- which I think I would not have necessarily felt beforehand. And I would like to think, and my children are little, so who knows maybe I’m messing up their lives completely at the moment. But I would like to think that in understanding how various humanity is and how much beauty there is ... I certainly want them to be happy, and it would be nice if they’re bright and I hope they’ll be successful and informed to a lot of ideals that seem valid to me, and have worked in my life. But I hope they turn out to be people who really have different ways, or different values, that I will have learned from all of this flexibility so I’ll be able to accept that, rather than rail against it.

You write that we often chart our own growth by noting how different we are from our parents -- but that parents cringe when talking about how different their kids are from them. Is that the next cultural shift that we need to have? A sense that a family can be different?

Yes. And I don’t think that there is anything wrong with a mom and a dad and two kids in the suburbs. I grew up with a mom and a dad in the city, rather than the suburbs, but what was in many ways a conventional nuclear family. The different kinds of families don’t threaten the so-called normal families. I’m certainly not saying we shouldn’t have any more mom and dad families in the suburbs. I think there are many people for who that works wonderfully. And I think it’s a nice pathway to have; I just don’t think there’s any reason for it to be the only thing that we have. I think it’s a kind of monoculture, which is very dangerous.

I like to think that you want diversity of family structure; you want diversity of love; diversity is a good thing altogether. You want to feel as though there are various ways of doing things and various points of view, and none of them is stigmatized. And, you can then say, okay, is this a family that is organized around people’s genuine love for one another? When I feel like the answer to that question is yes, that’s what constitutes keeping a loving family alive. And the idea that it has to look like this and there has to be 2.2 children -- that seems to me to be an idea that is oppressive and outdated and, in my view, I’m ashamed it ever held the edge on me that it did.

But I can’t go back and fix 1955. It's the 21st century and let's look at something brighter and more open. I gave a reading in Washington, D.C., on Friday, and one guy got up and asked "How do you intend to raise your children?" He was an older man and he clearly just couldn’t understand how it worked.

And I said how did you raise your children? Take care of them day-to-day and try to point them in the right direction, that’s how you raise your children. And I hope we get to the point when a question like that, which I have to say a lot of the audience even now responded to with a kind of rolling of the eyes, I hope that it will become a question that no one will think to ask.

Shares