The need for a “grand bargain” involving taxes and entitlements — in the next few years, if not immediately — has moved to the center of discussion in Washington. But it’s the wrong grand bargain — and a very bad deal for Middle America.

According to the conventional wisdom, any grand bargain should be modeled on plans like the Bowles-Simpson plan or the Rivlin-Domenici plan — financing lower tax rates on the rich by closing tax loopholes and cutting Social Security and Medicare. In the aftermath of an election in which the candidates of the rich were trounced at the polls, America’s plutocratic conservatives might be satisfied with merely maintaining existing low tax rates on the rich, while capping loopholes and cutting Social Security and Medicare.

This entire approach should be rejected. It is based on two fallacies — first, that the existing low (or lower) personal income tax rates on the rich promote growth, and second, that America can’t afford Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid in the decades to come. A number of “astroturf” propaganda groups in Washington and elsewhere will be paid tens of millions of dollars in the next few months by the conservative Republican billionaire Pete Peterson and his allies to repeat these fallacies and get Beltway pundits and journalists to parrot them. But endless repetition does not turn fallacies into facts.

America does need long-term reforms to its entitlement system and tax system — but they have nothing to do with the specious reforms peddled by Alan Simpson, Erskine Bowles, Alice Rivlin, Pete Peterson and allied CEOs. In addition to regulating excessive healthcare costs, the United States needs a middle-class welfare state that is bigger, not smaller. It’s the restricted, elitist private welfare state that needs to be cut, not the universal public social insurance system.

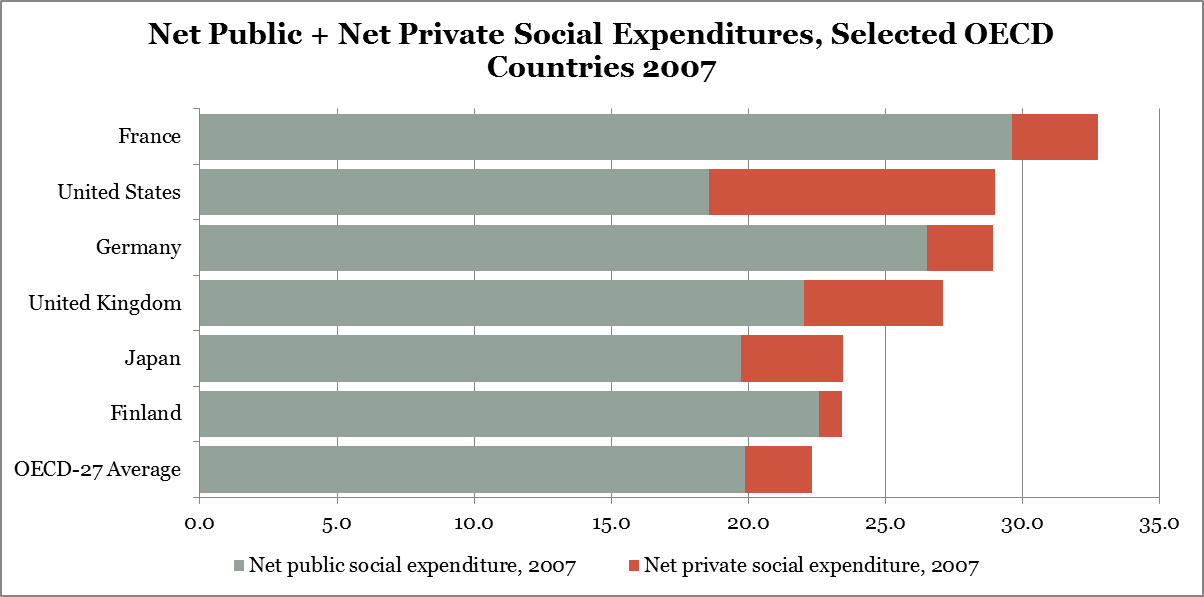

Let’s start with the spending side. As the two charts below demonstrate, the U.S. is unique among advanced industrial countries in relying heavily on private social expenditures rather than public programs to provide economic security to its citizens:

Retirement security provides an example of the mix of public and private benefits in America’s welfare state. As Steven Hill points out, in most similar countries the equivalent of Social Security replaces much more of pre-retirement income than America’s Social Security program does. In the U.S., however, tax-favored private benefits — employer pensions, 401Ks and IRAs — are supposed to make up for stingy Social Security benefits, which today average a mere $1,200 a month. If the deficit hawks get their way, then even this pittance will be cut.

The problem is that America’s tax-favored private retirement benefit system is grossly inferior to Social Security. Everybody gets Social Security, but only a minority of Americans have employer pensions or 401K accounts. The costs of pensions have burdened many companies, while two stock market crashes in less than a decade proved how unreliable 401Ks and similar tax-favored private savings and investment accounts can be.

Even worse, unscrupulous money managers capture many of the returns from private investments for themselves via deceptive fees. With a growing population of elderly Americans afflicted by Alzheimer’s, the fine-print artists peddling deceptive retirement products will have a field day.

Any rational person, with no personal pecuniary interest involved, would conclude that we should expand the stable, efficient, low-overhead public part of America’s retirement security system — Social Security — while cutting back the failed, inefficient and unreliable parts — tax-favored employer pensions and individual retirement savings accounts like 401Ks. Instead, we are barraged with propaganda demanding that we cut Social Security, the successful public program, and expand the private savings alternatives like 401Ks and IRAs that have failed so miserably.

Why? The answer is that Wall Street wants to charge fees on as much of our retirement money as it can get its tentacles on. The well-funded campaign to partly privatize Social Security under George W. Bush failed. But the same forces want to achieve the same result indirectly, by getting Obama and enough conservative Democrats in Congress, along with the GOP, to cut Social Security. Their manifest objective is to compel Americans to try to make up the losses in public benefits by gambling more with their savings in mutual funds, from which hefty profits will be skimmed by overpaid money managers.

Medicare and Medicaid are different from Social Security, because they involve the very structure of the U.S. medical-industrial complex. But the basic policy choice is similar. Is the goal of reform to enrich fee-skimming middlemen belonging to the 1 percent by forcing Americans to channel their healthcare spending, like their retirement savings, through private corporations? Or is the goal to provide universal health security along with universal retirement security by the simplest and most efficient means?

Achieving the latter goal requires somewhat bigger government — but only on paper. Today the actual scale of government is disguised, because politicians and policymakers fail to describe tax-favored private health insurance and private retirement saving accounts as “government” or “entitlements.” In public discourse we need to expand the definition of “entitlements” to include the tax-favored private savings and health insurance that chiefly benefit the few, not just the public spending programs that benefit the many.

If our objective is what is good for most Americans, rather than what enriches parasitic middlemen, then we should reduce inefficient and inequitable tax-favored private spending on retirement and health benefits and use the savings to increase more direct, fair and efficient public spending, including an expansion of Social Security. The alternative of cutting public benefits while favoring private benefits through the tax code means bigger, guaranteed windfall fees for America’s bloated financial industry — forever.

Shares