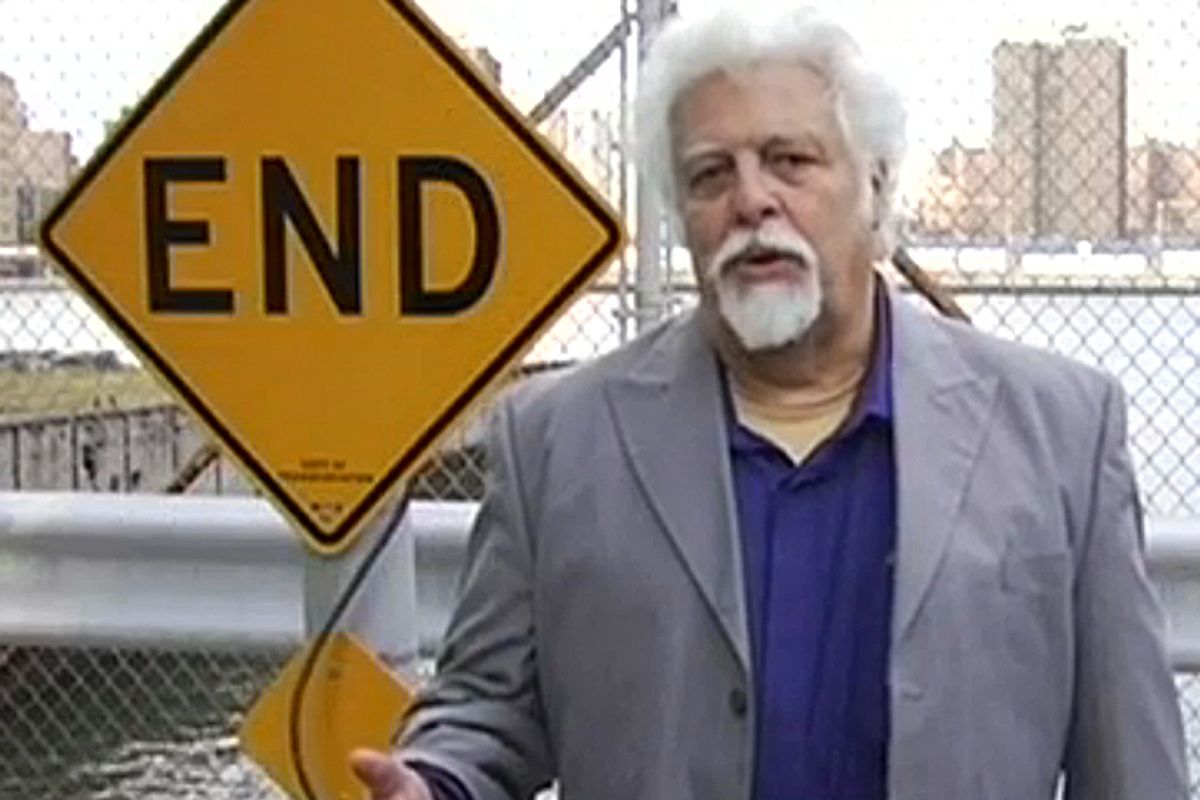

Spain Rodriguez, the celebrated underground cartoonist, died Wednesday at his home in San Francisco at age 72. Along with friends and co-conspirators like R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman, S. Clay Wilson, Bill Griffith and Kim Deitch, Spain turned comics into a powerfully subversive medium. None of his illustrious pen-and-ink contemporaries were better at capturing the raw, weird beauty or the macabre humor of growing up in Cold War America. He was a master at evoking the sensual power of the city streets: thickly built bad girls, greaser Romeos, ducktailed doo-wop singers. He was an American original.

Born into a blue-collar Buffalo family with a left-wing immigrant heritage, Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez had an instinctual feeling for the underdog. He did stints in foundries where the pounding metal-on-metal percussion was so loud that men went deaf. He rode with a local biker gang, and got into barroom brawls. When the revolution began in the 1960s, he immediately knew what side he was on: “When I was a kid, I kinda didn’t like rich people…I just kinda had a bad attitude.”

Heading for New York’s Lower East Side, he fell in with the equally scruffy radicals putting out the East Village Other newspaper, and invented his most famous character – Trashman – scourge of the rich and powerful. Later he headed west to San Francisco, as it was becoming the Emerald City of the cultural revolution. He hooked up with Robert Crumb, a young refugee from a military family in the Midwest, and became part of the legendary Zap Comics troupe, which did much to give the 1960s its signature psychedelic realism look.

Spain was an intoxicating storyteller, and he unspooled his tales of juvenile delinquent Buffalo, or Lower East Side junkie heaven, or acid-dreamy San Francisco with an Old World leisure. His stories often took weird twists and turns, and had moments of startling violence. But Spain was more a lover than a fighter, and – with his raffish mane, bad-boy goatee, and dark-eyed good looks – he tended to attract women who were not altogether appropriate. I recall one story about a San Francisco femme fatale who locked Spain in her apartment while she went out and turned tricks for drugs. On another occasion, young Spain fell into the clutches of the notoriously libidinous Janis Joplin. His description of their affair was touching in its gentlemanly restraint: “Uh, she was a kinda forward gal.”

By the time I met Spain, he was pushing 60, happily married to documentary filmmaker Susan Stern and the father of a daughter named Nora. But he was still pushing the edges with his work. One day, near the turn of the millennium, he and a sidekick – cartoon story-writer Bob Callahan – appeared in the offices of Salon, which I was then editing, carrying sketches for a cartoon series they called “The Dark Hotel.” Managing editor Gary Kamiya – who became the story editor for the series – and I were immediately captivated by “The Dark Hotel’s” weird tunnel into the American psyche. Set in a seedy San Francisco Tenderloin hotel, the series – which ran for several months in Salon – featured Balkan war criminals on the lam, CIA drug experimenters, George W. Bush bagmen and other creatures from the dark side of Spain and Bob’s America.

Spain had a lover’s quarrel with his country. Deeply versed in history, he was keenly aware of America’s corruptions and outrages. But he never gave up on America, and even as he fought his final round with prostate cancer, he stayed tuned into the ups and downs of the presidential campaign, rooting for the imperfect Obama, whom he had campaigned for in 2008. “My hopes are that mankind will build a more just society,” he said as he neared death, in a film about his life that is being made by his wife. Although Spain could come across as the original hipster, there was nothing ironic or detached about Spain when he made these kind of openhearted comments.

Spain, who grew up on the gritty action men of EC Comics, believed in heroes and villains. He knew about Smedley Butler – the Marine hero who turned against U.S. imperialism and later helped rescue Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency from a Wall Street coup – long before I did. In 2010, Spain and I collaborated on a “pulp history” book about this real American hero, titled “Devil Dog.” One of the wonderful quirks I learned about Spain while working on “Devil Dog” with him was that this son of anarchists and socialists had a shameless passion for military uniforms and regalia. He collected whole battalions of toy soldiers from all nations and eras. And when I gave him a US Marine Corps picture book, filled with historic images of leatherneck uniforms and other memorabilia, Spain became as a giddy as a boy.

Spain loved to share his latest enthusiasms – like the Russian military chorus he found somewhere online that was fond of singing Irish ballads. At a Christmas dinner party at my house not long ago, where every guest was required to sing a song or recite a poem for their meal, Spain shyly held back until the very end. Finally, as he was heading toward the door near the conclusion of the evening, he suddenly turned around and began booming out a robust version of a song he had learned as a boy, “No Pasaran!” – the anthem of the anti-fascists during the Spanish Civil War. It was random, heartfelt, and totally Spain.

In his later years, Spain’s thick, wavy mane turned snow-white. He lived around the corner from me in San Francisco, and I would catch sight of him on a daily stroll, the lion in winter. He never seemed old or inaccessible to young people. My sons, now 18 and 22, and trying to figure out their own creative paths, felt instantly drawn to Spain, with whom they could talk about everything from film noir classics like “The Third Man” to vintage cars to the gangs that originally populated our streets when we first moved into the neighborhood. Spain loved to teach, loved to pass on to a younger generation what he knew about cartooning and life. He was teaching my younger son Nat how to draw – and, of course, filling up his head with all his stories of an older, weirder America.

When Spain was a boy in the 1950s, there was a public uproar about the kind of strange and shocking comics he loved to read. The hysteria led to congressional hearings in 1954 and a crackdown on the freedom of comics. One puffed up professor called the insidious effect of comics “the seduction of the innocent.” To Spain Rodriguez’s credit, he never listened to the censors and bluenoses. He allowed himself to be seduced. And his twisted and true comic art will continue to subvert generations for years to come.

* * *

One of the final pieces of work produced by Spain Rodriguez was the illustrated tale of a shameful moment from the career of soldier and future president Andrew Jackson. The panel was to be part of an ongoing “pulp history” series for Salon. Rodriguez collaborated with storytellers Karen Stanford and Gary Kamiya on this piece.

Shares