In the months following 9/11, Republican President George W. Bush spoke passionately about the need to respect Muslim-Americans and "the vibrant faith of Islam, which inspires countless individuals to lead lives of honesty, integrity, and morality.” This year, every Republican presidential candidate united in seeing Islamic Shariah law as a threat to the United States, despite a total lack of evidence.

Anti-Muslim attitudes are now much higher than they were immediately following 9/11. Islamophobic rhetoric once unacceptable in public discourse is now commonplace. And there are now over 50 controversies raging across the country about whether Muslims should be allowed to construct houses of worship. How did we get from there to here?

Part of it is that anti-Muslim fringe groups have learned how to essentially hack the media by taking advantage of the fact that reporters are drawn to highly visible displays of emotion and fear, argues Christopher Bail, a sociologist who studies the media at the University of North Carolina and University of Michigan.

In a new quantitative analysis published in the American Sociological Review, Bail reports that radical anti-Shariah groups’ messages have been “heavily overrepresented” in the public discourse, whereas pro-Muslim voices have been largely underrepresented. The lopsided media coverage has had far-ranging consequences, elevating the visibility of these radical groups, their perception of their credibility, and creating “a gravitational pull on the mainstream” that moves it towards the fringe position.

“Angry and fearful fringe organizations not only exerted powerful influence on media discourse about Muslims in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, but ultimately became some of the most influential mainstream groups in the field,” he writes. “By 2008, these fringe organizations not only permeated the mainstream but also forged vast social networks that consolidated their capacity to create cultural change.”

Bail used plagiarism detection software to trace how the language from press releases of over 120 different groups with a diversity of views on Muslims ended up in the media. He compared the language in the press release to over 50,000 news articles and TV transcripts and found the fringe views to be vastly more represented than mainstream or pro-Muslim views. Meanwhile, looking at IRS disclosure forms, he found that over time, fringe groups increasingly shared board members and personal ties with mainstream conservative groups like the American Enterprise Institute as their views were mainstreamed by the media.

“This isn’t simply a story about Fox News being Fox News,” Bail told Salon. Rather, it extends to all mainstream media outlets. But it's not necessarily the journalists' fault either. “It’s not really about irresponsible media. It’s a product of this emotional energy,” he says.

Psychological research has demonstrated that in times of crisis, people respond most acutely to emotionally strong voices, Bail explains. The media industry has long understood this intuitively and featured dramatic, colorful and emotional figures because they’re more compelling to readers. We've all seen this “fringe effect,” as Bail dubs it, from the Tea Party to the birther movement.

On one hand, there's an issue of reporters uncritically citing self-described terrorism experts like Robert Spencer or Steve Emerson, who see Islam itself as the driver of terrorism. In the wake of 9/11, journalists genuinely struggled to find voices that accurately represented Islam, and by simply being outspoken, they end up getting cited by the media as experts. Thus, they become perceived as experts, whether or not they actually are.

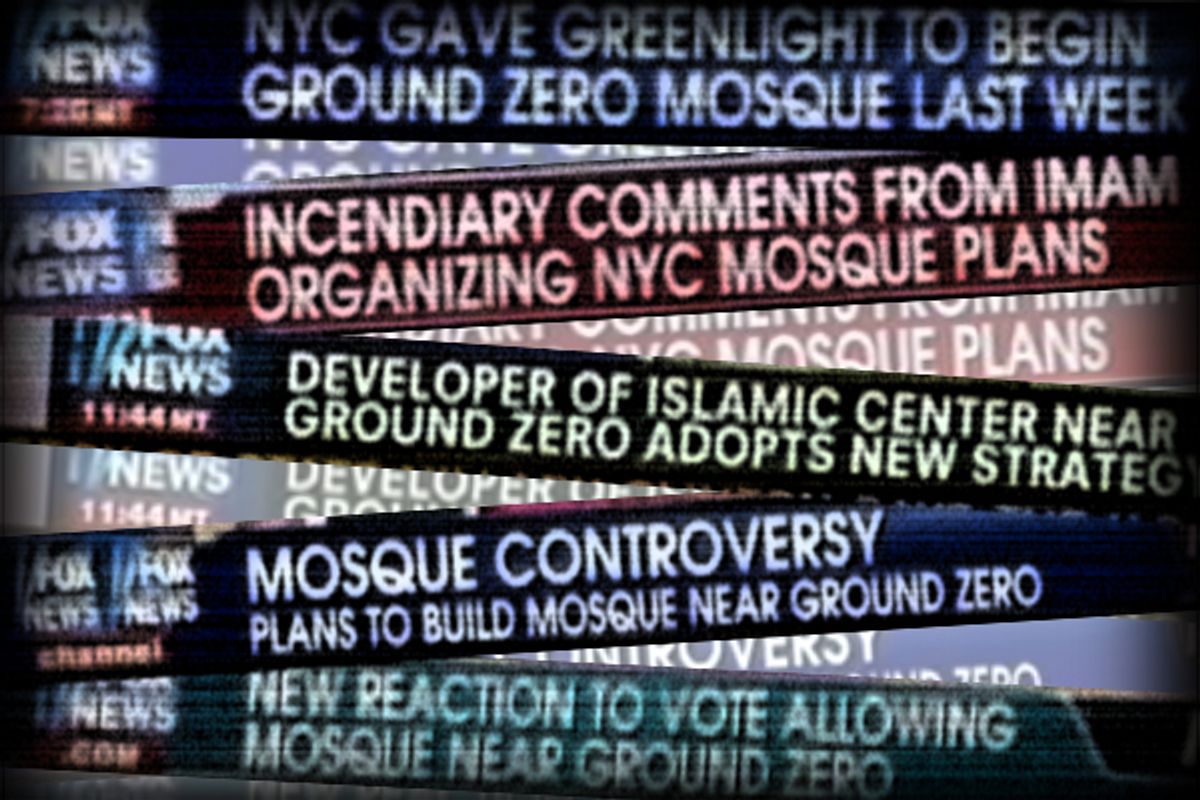

On the other hand, the media can also help fringe figures by criticizing them, ironically. “It’s a classic Catch-22,” he said. Just think about Terry Jones, the Florida preacher with a congregation of fewer than 50 who came to command the world’s attention for several tense weeks in the fall of 2010 when he threatened to burn a Quran. Or the controversy over the so-called Ground Zero Mosque, which mushroomed into a national crisis after blogger Pam Geller captured the media's attention despite having a tiny audience and a propensity to compare Muslim-tolerant Jews to Nazi sympathizers or suggest that critical journalists are training to be suicide bombers. If the media hadn't paid attention to them, would they have mattered?

So what can be done to break this feedback loop? “One of the tragic parts is that there isn’t much that can be done,” Bail acknowledged. Ignoring the fringe is the obvious answer, but that won’t work when they can get their message out through their own media outlets and social media, thanks to the Internet.

One positive step would be to bolster pro-Muslim groups. They’ve had far less success in getting attention when they condemn terrorism, for instance. Bail says this is because they’ve failed to learn the lesson of the fringe and appeal to people's emotions. “It’s not that they’re not condemning [terror], it’s that they’re not doing it with an emotional valence,” he said, and thus it goes largely unnoticed. Muslim leaders are often angrier about terrorism than anyone else because they have to defend themselves on a daily basis, he said, but they don’t let that anger show in public.

Of course, to get too angry could play into their anti-Muslim stereotypes. Indeed, Bail said this is a problem when Muslim groups react passionately to Islamophobia, leading the opposition to unfairly portray them as speaking publicly only when attacked, and not when non-Muslims get attacked by terror.

It's not a particularly flattering portrayal of the media, but a host of perhaps perverse incentives leads journalists to the extreme and sensational and emotional and those seeking to get their message out may just have to play along.

Shares