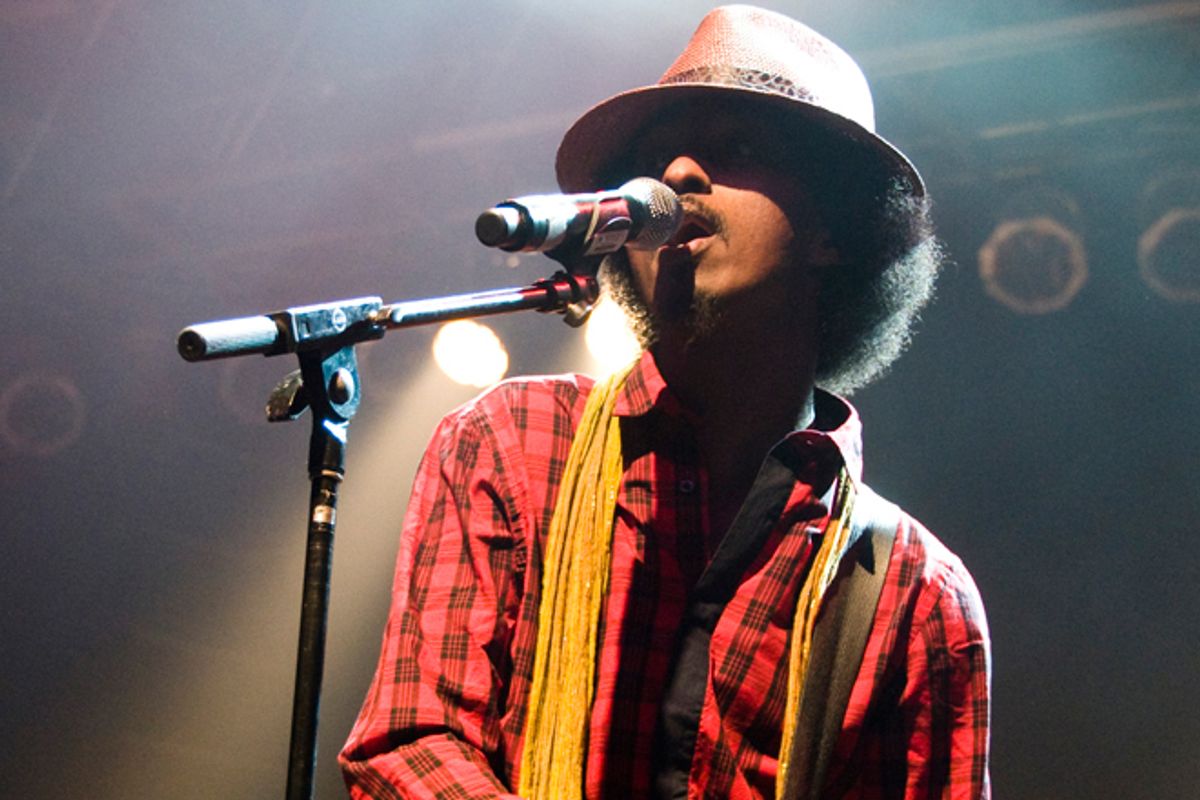

The Somali-Canadian rapper K’naan shone a light on one of the record industry’s more shortsighted practices over the weekend in the New York Times, when he wrote about the ways in which his label undermined his artistic self-confidence.

If only he would stop rhyming so much about the turbulence of his native Somalia and start catering to radio station program directors and the tastes of American teenagers, he could be huge, the record company suggested. They said, in essence, we have this stale little formula that makes everything sound the same, and all you have do is simply change everything that has made you successful so far. Whaddya say?

K’naan wrote that he gave in, going so far as to Westernize the names in his songs and work with “A-list producers” in an attempt to expand his audience before coming to the conclusion that “packaging me as an idolized star to the pop market in America cannot work.”

And it probably won't, but that never stops the major labels from trying. Desperate for the infusions of cash that a hit can yield, they persist in thinking that imitating success is its own recipe for success, so they sign artists like K’naan and then try to sand away their originality to make them sound like whatever is currently popular on Top-40 radio. That’s where the producers come in.

Although they don’t always get the credit, record producers have played an outsize role in shaping the sounds that come to define eras — a role that is evolving as music moves deeper into the digital realm.

Since the dawn of rock ’n’ roll in the 1950s, producers have tended to fall into one of two categories. There were the shepherds like Sun Records impresario Sam Phillips, who helped steer and sharpen the natural gifts of singers like Elvis Presley or Johnny Cash. Then there were the song czars, like Phil Spector, who created the sound they wanted first, and then found a singer to complement it.

The song czars are running the show these days, with producers like Dr. Luke, Max Martin, Benny Blanco, Stargate and The-Dream taking a leading role in creating mass-culture pop music. In fact, if we’re honest about it, they’re the ones who have dominated the pop charts in recent years, writing and producing a run of hits sung by pretty-faced surrogates including Katy Perry, Ke$ha, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Rihanna and the latest semi-robotic iteration of Britney Spears.

“The pop world, it is sort of run by the producers,” says Emily Wright, a vocal producer and Grammy-nominated engineer who works with Dr. Luke. “Luke is involved on the writing side, I would say, about 98 percent of the time, and every once in a while he’ll come in and produce something. That’s so rare: Usually he’s creating from the ground up.”

That’s not new: Spector had a hand in writing many of the biggest songs the Ronettes and Righteous Brothers sang, while disco-era producers like Nile Rogers and Bernard Edwards wrote and produced entire albums for Diana Ross and Sister Sledge. It is, however, vastly different from the song-shepherd model that took hold in rock music in the 1960s and ’70s. Their role was often to simply help bands sound the way they wanted to, whether it was George Martin and the Beatles, Jimmy Miller’s work on a string of acclaimed albums by the Rolling Stones or Columbia Records house producer Bob Johnston assisting Bob Dylan, among plenty of others. The best producers made good bands better: They knew how to get a certain guitar sound, how to make the drums really pop or when to help the artist polish a bridge or a chorus.

Their success led to demand as bands sought to work with the architects of the sounds that influenced them, a circle that came to include the likes of Daniel Lanois (U2, Dylan), T-Bone Burnett (Counting Crows, the Wallflowers) and Rick Rubin (a ton of artists, from the Beastie Boys to Tom Petty, Johnny Cash to Metallica). Producers played a vital role in the growth of alternative, rock, too, where certain names conferred automatic music credibility: for example, Butch Vig, who produced Nirvana’s “Nevermind”; or Steve Albini, who rejects the title “producer” yet still brought his distinctive aesthetic to albums by the Pixies, PJ Harvey and more. More recently, the indie world has embraced shepherd producers like John Congleton, Peter Katis and John Agnello, who have worked on many of the best indie records of the 2000s so far, from the Mountain Goats (Congleton) to the National (Katis) to the Hold Steady (Agnello).

Yet theirs is an increasingly marginalized art. Although the shepherds and the czars have been alternately ascendant over the years, the shepherds may well be facing a future in which they are reduced to a specialized niche status, thanks to technology. After all, the perfect snare-drum sound doesn’t mean so much when songs are built, one instrumental track at a time, with synthesizers and software. Pop songwriters these days are beatmakers, and the MacBook is the primary tool of their trade — so much so that more traditional analog studios are disappearing. (One of those bygone rooms, the Los Angeles studio Sound City, is the subject of a forthcoming hagiographic documentary by Dave Grohl.)

“It’s a lot different now because a lot of the younger kids don’t really sit in a room with older people who really know how to make records and steal ideas,” says Agnello, who half-jokingly defines his own aesthetic as “everything I know about recording, I stole from my mentor.” “I know there are young guys out there who have a grasp on it, but I think the dearth of actual recording studios and the more commonplace thing of people doing stuff in computers and cutting and pasting, that’s more how people do records.”

Lest the anti-rockist crowd begin polluting themselves with fury, that’s not a value judgment about the superiority of the guitar-dude hegemony (or whatever): Some of the catchiest, most memorable songs of this year are computerized creations, including Psy’s “Gangnam Style” (which he produced himself) and Taylor Swift’s collaboration with Max Martin on “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together.”

It is, however, a homogeneity judgment. Like the song shepherds, the czars have established aesthetics of their own. The difference is that because they’re also writing the songs, their aesthetic doesn’t merely color the music, it is the music. Record labels don’t care about helping an artist like K’naan develop his own voice — they want to pair him with song czars so that he’ll sound like them. The result is a cloistered pop realm dominated by a handful of producers who are adept at churning out tunes that are at once catchy and formulaic — for an extreme example, listen to Beyoncé’s “Halo” back to back with Kelly Clarkson’s “Already Gone,” both of which were written by Ryan Tedder. (The New Yorker offered a lengthy account earlier this year of how pop hits are created.)

Every era produces plenty of forgettable pop music, and judging in the moment what is destined to be memorable down the road is a risky exercise. Some of the song czars’ productions will surely make the cut, which is all the more impressive given that they’re designed for an industry wholly obsessed with what’s hot now. It’s a safe bet, though, that K’naan’s most memorable songs will be the ones that sound like him and not like them.

Shares