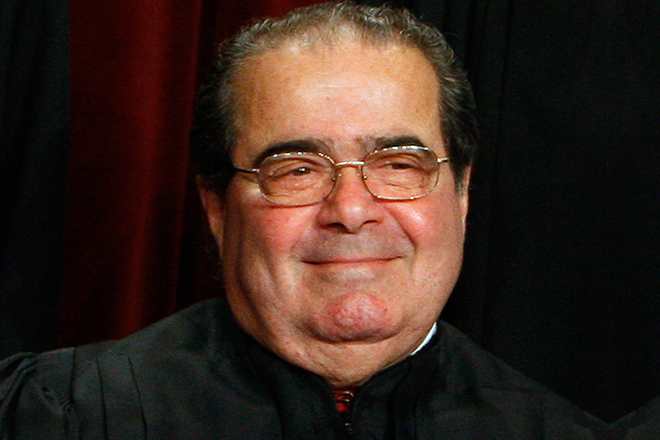

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia on Monday found himself defending his legal writings that some find offensive and anti-gay.

Speaking at Princeton University, Scalia was asked by a gay student why he equates laws banning sodomy with those barring bestiality and murder.

“I don’t think it’s necessary, but I think it’s effective,” Scalia said, adding that legislative bodies can ban what they believe to be immoral.

Scalia has been giving speeches around the country to promote his new book, “Reading Law,” and his lecture at Princeton comes just days after the court agreed to take on two cases that challenge the federal Defense of Marriage Act, which defines marriage as between a man and a woman.

Some in the audience who had come to hear Scalia speak about his book applauded but more of those who attended the lecture clapped at freshman Duncan Hosie’s question.

“It’s a form of argument that I thought you would have known, which is called the ‘reduction to the absurd,'” Scalia told Hosie of San Francisco during the question-and-answer period. “If we cannot have moral feelings against homosexuality, can we have it against murder? Can we have it against other things?”

Scalia said he is not equating sodomy with murder but drawing a parallel between the bans on both.

Then he deadpanned: “I’m surprised you aren’t persuaded.”

Hosie said afterward that he was not persuaded by Scalia’s answer. He said he believes Scalia’s writings tend to “dehumanize” gays.

As Scalia often does in public speaking, he cracked wise, taking aim mostly at those who view the Constitution as a “living document” that changes with the times.

“It isn’t a living document,” Scalia said. “It’s dead, dead, dead, dead.”

He said that people who see the Constitution as changing often argue they are taking the more flexible approach. But their true goal is to set policy permanently, he said.

“My Constitution is a very flexible one,” he said. “There’s nothing in there about abortion. It’s up to the citizens. … The same with the death penalty.”

Scalia said that interpreting laws requires adherence to the words used and to their meanings at the time they were written.