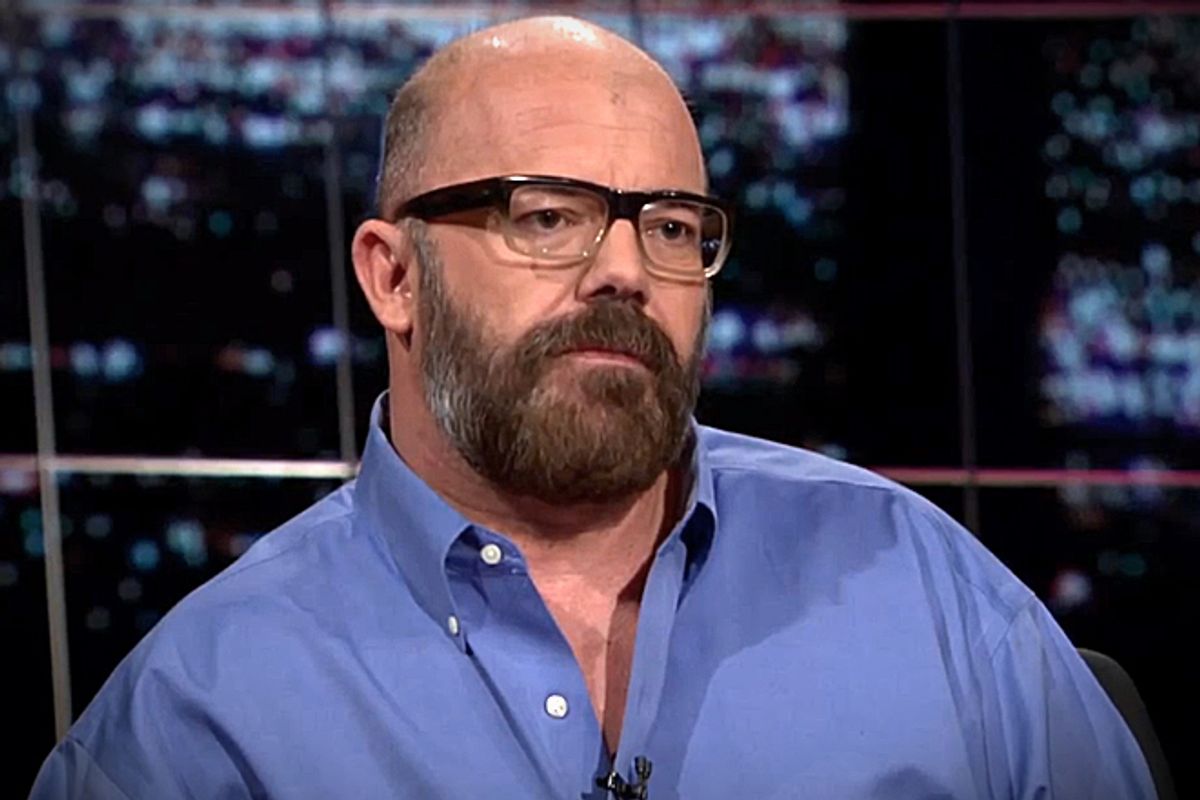

Extra! Extra! The Daily Dish is going independent. Andrew Sullivan, blogger extraordinaire, declared today that his venerable, high-profile, prolific blogging operation will no longer depend on the largess of corporate owners like Time, the Atlantic or the Daily Beast to operate. He's going indie, and depending on readers to pay up.

The announcement sent shock waves through Twitter. It's a risky, bold move. Very few people have figured out how to get readers to pay for content on the Web. Sullivan's model is innovative: He plans to eschew advertising altogether. Instead, we get what he has dubbed "freemium-based metering."

Our particular version will be a meter that will be counted every time you hit a "Read on" button to expand or contract a lengthy post. You'll have a limited number of free read-ons a month, before we hit you up for $19.99. Everything else on the Dish will remain free. No link from another blog to us will ever be counted for the meter - so no blogger or writer need ever worry that a link to us will push their readers into a paywall. It won't. Ever. There is no paywall. Just a freemium-based meter. We've tried to maximize what's freely available, while monetizing those parts of the Dish where true Dishheads reside. The only tough love we're offering is the answer to the View From Your Window Contest. You'll have to become a member to find where the place is. Ha!

Salon is as interested as anyone in the question of how to make online journalism profitable. We fired off some quick questions to Andrew, and he was gracious enough to respond near-instantaneously.

Our elephant-like memory at Salon recalls you not being too complimentary of our initial efforts to get readers to pay for content way back in Neolithic time. What's changed? What makes you think you can do this, when so many have failed?

Busted. I always dismissed this. But the online world has changed a lot since I began 12 and a bit years ago. Banner online advertising is increasingly weak for general interest sites and the web has evolved. The success of the New York Times' freemium model is what struck me the most. Finding a way to keep almost all the content available while getting your core readership to support it is now, I think, within reach for more than just the NYT. We may fail. But we wanted to try.

Isn't there an awful lot riding on this? You are one of the most, if not the most, prominent bloggers in the English-speaking world. You've also been super-successful -- building a big staff, getting your healthcare paid for, et cetera. What happens if this experiment fails, and you find out that you can't pay for your staff and your bandwidth and your healthcare? What will that say for business models for online journalism?

It will be depressing for business models for journalism. But look: With every jump like this, there's a risk of failure. We know that. If we fail to make a decent living at this, we will find other ways to make a living. But if we succeed, we will have helped pioneer a new model for online journalism: lean, reader-based and ad-free. Rather than stay in the comfort of a big media company, we thought we should try and pioneer something. That's part of why I started the Dish when the MSM would have kept paying me handsomely to do old media. I'm interested in innovating. You only live once, and in my case, I never expected to live this long. So why the fuck not?

Is the kind of stuff you and your team produce the kind of stuff that readers will pay for? It's not original reporting, and mostly not breaking news. It's opinion. High-quality, prolific opinion, to be sure, but still, if there's one thing for which there is zero evidence of scarcity on the Web, it's opinion. What evidence do we have that readers will pay for riffs on the news, rather than the news itself?

None. Except that we got a couple of thousand members in the first hour, a third of them paying us more than the minimum price. We feel the Dish has a deep and special relationship with its readers and the readers are the people who made us believe this could work. When you've interacted with them for more than a decade, you get a sense of their commitment. Around 75 percent of our readers have bookmarked the Dish; the average time spent a day on the site is around 17 minutes. Eighty percent clock in twice a day. We thought they'd pay a nickel a day for full access. We may be wrong, but we'll find out soon enough.

Early reaction on Twitter is a mixture of people saying that if they'd pay for anybody online they'd pay for you, to mocking your metering plan, to jokes about the Daily Beast's "debt ceiling." It's a free-for-all out there, in every sense of the word. How do you stay relevant in that ferocious online give and take if you start metering access to content?

A huge amount of the Dish will remain free and available. Everything you see on the page, for example -- apart from longer posts with "read on" on them. Only these longer, deeper posts will require a meter. And all links to posts from outside the Dish will never hit a meter. So we're confident we'll be able to stay part of the mix of the Web the way we always have done.

A cynic might wonder how much this move might have to do with the Daily Beast/Newsweek's well-publicized financial troubles. Tina Brown spent an awful lot on name-brand writers for her online publishing effort, and the question has always been how could an online publishing model pay such high rent. Your announcement seems to suggest that, ultimately, Tina Brown couldn't afford you.

The truth is our contract was ending Dec. 31 and we had to decide to renew or not. We wanted to become independent for our own reasons, and Tina could see the logic. I also felt that if we could bypass the advertising morass and go straight to our readers for support, we might have a more stable future. It was a bet on the readership. It is a bet on the readership. So we're in their hands. There's something cathartic about that. And we all need to get people paying for content online or there will no longer be content online. So since we have a large, devoted readership, and a small staff, we thought we'd be an ideal vehicle to test these waters. And if you don't try, you'll never know.

Shares