THE FIRST CREATIVE WRITING CLASS I ever took, on the second floor of a mousy old building on Piano Row off Boston Common, was an introduction to Creative Nonfiction. The teacher, a young MFA grad, I found to be a lovely and warm resource who handed out copies of meaningful essays by famous essayists and encouraged us to read aloud our god-awful in-class exercises — maintaining her composure as one-by-one we read (or shyly passed on reading) about our first memories or a physical description of someone we loved.

THE FIRST CREATIVE WRITING CLASS I ever took, on the second floor of a mousy old building on Piano Row off Boston Common, was an introduction to Creative Nonfiction. The teacher, a young MFA grad, I found to be a lovely and warm resource who handed out copies of meaningful essays by famous essayists and encouraged us to read aloud our god-awful in-class exercises — maintaining her composure as one-by-one we read (or shyly passed on reading) about our first memories or a physical description of someone we loved.

She was a good teacher, but a curious quirk was her pronunciation of a word that came up frequently. I should have paid more attention to the graceful generosity she extended to her students because I am sure that I made a face or cocked a theatrically subtle head tilt whenever discussion turned to “mem-wah,” which, as you might imagine, was often. This pronunciation seemed not to fit with the rest of her general down-to-earthness. It was a baffling and bizarre affectation that I could in no way account for. What’s more, nobody else seemed affected by this affectation. Or maybe they were, but were polite enough to keep their eyebrow-raising and lip-pursing to themselves. As the weeks passed, I took the serious things she had to say about writing less seriously.

Pretention runs parallel to the absurd; the one needs the other, after all. When years later I took the Chinatown bus, the Fung Wah (almost rhymes with “mem-wah”), between Boston and New York for the last time, preparing for a move, I brought with me the notebook I used in her class, which I still consult, and the unconscious association between the whole genre and silly, stupid pomp.

Such remains the reputation of the memoir. (Or the me-moir.) Critics rip apart the conceit with more lust than goes into panning a Harlequin (probably even the act of bodice-ripping itself). Perennially gauche, the fad in critical bullying over the last year has been to bash freely — like when the NPR headline touted a few wonderful memoirs as ones that “won’t make you slit your wrists.” The memoir could be defined as autobiography that uses fictional, novelistic devices. But even that handy rule of thumb ranks fiction above all else, placing nonfiction leagues below. Maybe it is better to say that memoir is autobiography that relies less on chronology and more on good writing, which, in order to be aptly labeled, usually has to be seen — kind of like pornography. Randall Jarrell once said that a novel is “a prose narrative of some length that has something wrong with it.” Well, there are some critics who might define a memoir as a prose narrative of some length that has everything wrong with it.

The New York Times critic Neil Genzlinger would probably be one of them. He got the ball rolling in an essay that came out in 2011, “The Problem With Memoirs,” nobly calling for a moment of silence for “the lost art of shutting up” with all the dignity that typically accompanies snark. Genzlinger mourned for the time when only the famous had “earned” any kind of reflective autobiographical writing. (When this was, I have yet to figure out. Who was Frank Conroy before he wrote Stop-Time? Is Out of Africa not worth our time because Isak Dinesen was neither prime minister nor pinup in her native Denmark?) “Unremarkable lives went unremarked upon, the way God intended,” wrote Genzlinger. Sure, okay. What about the unremarkable lives led by unremarkable people who populate, well, all of literature? Who was Anna Karenina but some selfish, rich white lady who stepped out on her husband? Boring. Would somebody shut that Russian guy up, already?

The novelist Lorrie Moore took a more considered tack in her piece “What If?” in the New York Review of Books. I will read anything of hers, and this essay was full of skill and beauty. Still, it was an elegant shakedown of the entire genre, calling memoirs “jumbled confessions” destined to strive for the art of fiction but simply not capable of achieving the meaning found in novels. Besides that, argues Moore, they are not trustworthy, due to “the limits of memory and the demands of writing.”

So then why write a memoir? Let’s review: lack of imagination, cry for attention, therapeutic release, pathetic need for outside validation. All of these could easily be accomplished by starting a Grindr account or, for the minimally more inhibited, unbuttoning one’s blouse that extra button (or three) at the office. To reveal is to expose, after all, and what is more vulgar than plain-faced honesty? The memoir is the trench-coated flasher in the parking lot, a dust jacket cloaking the most private and shameful parts of our internal selves, and the reading community lives as do the victim-residents of Steven Millhauser’s traumatized suburb in “The Slap”: waiting to be accosted with yet another memoir.

Why not, then, as most writers do (including Ms. Moore I suspect) stick to covering up autobiography as fiction? Authors are equally dismissed for the sin of “memoir dressed as fiction” as was Ben Lerner’s brilliant novel Leaving the Atocha Station. As Lerner told The Believer, “It’s different to collapse the distinction between art and life within art, and to collapse the distinction between art and life in life.”

Maybe there is at least one more reason for memoir, ever so slightly more legitimate than an extended therapy session: because a story is better that way. While some require the freedom of fiction, what if some stories need the pressure of truth — not because a writer perceives reality or confession as more interesting or so different from fiction, but because there is a unique dialogue that happens only in memoir between the present and the past. The Liar’s Club, that memoir of memoirs, by Mary Karr, started out as a novel in a writing workshop across the river from Piano Row, in Cambridge. But fiction was not the optimal form for the story, which was not so very special, even if it does elicit a mild case of “catastrophe envy.” Karr’s ability to chart in clear, cold prose the convergence of the author and the various versions of herself as a bratty little girl from East Texas or a bratty poetry student — that’s what makes the book worth reading.

Could these first-person handicaps, “limits of memory” and “demands of writing” as Moore labels them, actually be tools for exploring the temporal, emotional distance among past selves? In his essay “Reflection and Retrospection,” Philip Lopate lays out these devices as absolutes for first-person writing:

In writing memoir, the trick, it seems to me, is to establish a double perspective, which will allow the reader to participate vicariously in the experience as it was lived. […] The author’s retrospective employment of a more mature intelligence to interpret the past […]is not merely an obligation but a privilege, an opportunity.

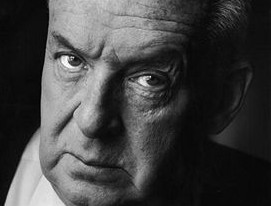

This division of selves can be seen very literally in the title of Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, Joseph Anton, which, among recent literary memoirs, most fits Neil Genzlinger’s requirements. Not only is Rushdie a prestigious, award-winning author, he is also a bona fide celebrity, maybe even the most infamous author since post-Lolita Nabokov. On Valentine’s Day, 1989, the Iranian ayatollah issued a fatwa, sentencing Rushdie to death for having offended Islam with his book the Satanic Verses. The “A” squad of special branch ministry police are assigned to him by the government, and he is told that, after the queen, he’s the most threatened British citizen in the country. All of the members on the team, it is emphasized, are volunteers. When asked to choose an alias, he naturally chooses one from literature. “He thought of writers he loved and tried combinations of their names. Vladimir Joyce. Marcel Beckett. Franz Sterne. He made lists of such combinations and all of them sounded ridiculous. Then he found one that did not. And there it was, his name for the next eleven years.”

Enter Joseph Anton.

The morning of the fatwa is also the day of Bruce Chatwin’s funeral, and Rushdie sits next to Martin Amis and Paul Theroux, who says, “I suppose we’ll be here for you next week, Salman.” This is the kind of dishy behind-the-scenes scene populated by other celebrities that Genzlinger craves, and we get plenty of them in Joseph Anton. (Bill Buford is revealed to have slept with Rushdie’s second wife; Vaclav Havel backs out of a meeting due to security fears; Rushdie’s two-timing model wife Padma Lakshmi was “just too damn gorgeous to leave.”)

In The Art of Time in Memoir, the critic and essayist Sven Birkerts lays down this essential (which I hope will take off as much as Lopate’s double-perspective maxim): “Memoir begins not with event but with the intuition of meaning — with the mysterious fact that life can sometimes step free from the chaos of contingency and become story.”

Rushdie’s got the event and the chaos that follows, but the search for meaning falls short; he narrates as if he were both the unhinged biographer Kinbote and the demure genius John Shade. Many of those sins defined by critics of the genre — the self-aggrandizing and the need for validation — seem highlighted by Rushdie’s choice to write of himself in the third person. “Acting was his unscratched itch,” he confesses of his cameo in Bridget Jones’s Diary. Where is the intuitive reflection that might temper such a frivolous revelation with something more meaningful? If any writer might accomplish the impossible and make such a connection, it would be Rushdie. He has a flair for mythologizing, with an unmatched gift to translate the squalors of life into lush fairy tales. The most enjoyable passages of Joseph Anton pop up when his autobiographical writing approaches the rich, bacchanalian writing of his fiction, which only seems to happen when he writes of his childhood in India, and especially when describing his mother Negin:

She was a gossip of world class, and sitting on her bed pressing her feet the way she liked him to, he, her eldest child and only son, drank in the delicious and sometimes salacious local news she carried in her head, the gigantic branching interwoven forests of whispering family trees she bore within her, hung with the juicy forbidden fruit of scandal.

For fans of Midnight’s Children (I admit to having read it half a dozen times), this discovery is especially delightful. Both Negin Rushdie and Amina Sinai pour all of their love into their children, while bearing the alcoholic rages of abusive husbands who were not their first choices for marriage. From Midnight’s Children, which won the Booker of Booker prizes in 2008:

Once upon a time there was a mother who, in order to become a mother, had agreed to change her name; who set herself the task of falling in love with her husband bit-by-bit, but who could never manage to love one part, the part, curiously enough, which made possible her motherhood; whose feet were hobbled by verrucas and whose shoulders were stooped beneath the accumulating guilts of the world; whose husband’s unlovable organ failed to recover from the effects of a freeze; and who, like her husband, finally succumbed to the mysteries of telephones, spending long minutes listening to the words of wrong-number callers.

How lovely is this adult-sized mythology, drowned in nostalgia, where nothing happens happily ever after, and life’s sensual pleasures must come from storytelling itself. What swirling, careening momentum of tragedy in the prose. In both Negin’s and Amina’s passages. Here is disaster colored by longing, lore steeped in love and recorded to keep alive a place, in both his fiction and his biography. We want to know Salman Rushdie, or Joseph Anton, as Negin’s son, not as the world-famous writer, whose memoir unfolds mostly absent of the complexities of reflection, in a kind of queasy self-loathing that offers the mundane descriptions of a very important man’s day-to-day minutiae (and his acutely rationalized womanizing).

I wish we had another book, fiction or non-, from Marco Roth to compare with the n+1 founder’s memoir. The Scientists: A Family Romance is his first, the story of Roth’s losing his scientist father to AIDS and the anger and confusion that drives him forward. As he goes through high school, his father is dying at home on the couch, purportedly the victim of a lab accident involving contaminated blood. “Repetition is the mother of memory,” says his father, a distant man who seeks to connect with his only child through literature. Roth recounts his days at Columbia and Yale, where he becomes a scholar of Comp Lit. He laces his father’s scientific language throughout his own, noticing tattoos that look like molecules and rhomboid patterns in carpets; even without the pedigree we see that he is expert in all the techniques of fiction. He writes, “The couch where my father died was also the couch where he taught me to read. I might as well start there: my alpha and his omega joined by a piece of furniture.”

In Roth’s memoir there is an especially beautiful description of Damascus ice cream, a fabled dessert a friend uses to try and lure him into a trip to Syria: “She said it was like no other ice cream in the world, rose and pistachio flavors of a cream so rich it was rolled out in sheets and hung on hooks, without melting.” This bright image conjures up both the fabulously rich dessert and the double helix — a joy to consume through the words, but I often found myself wondering what the person on the page was thinking.

The Scientists is set up as a mystery, one the reader has already solved by the time that first lie about how Roth’s father contracted AIDS is spun; perplexingly, Roth spends most of the book denying what we have long figured out. We feel the deception on the part of Roth’s parents, and then on the part of Roth the writer when he repeats and repeats the doubtful story of accidental HIV infection. When his aunt writes her own memoir outing Roth’s father as gay, he throws an understandable tantrum and vows to write his own story.

But what is that story? Is it his search for the truth? He questions his father’s friends, but refuses outright to believe them when they confess their suspicions. If this is his way of accepting his father’s sexual orientation, it is only by turns; Roth never acknowledges it directly, even when, in the last few pages of the book, his mother takes him on a walk and reveals to him that she knew his father had male lovers. Had I been stupid, blundering and insensitive?” Roth asks too late in the game.

Up rose a flash of memory showing me my father reading the gay British historian A. L. Rowse’s Homosexuals in History. […] Right there an invitation, perhaps for me to ask why he was reading it. I had filed it under general culture, the library of every civilized person. I had missed everything, missed my parents’ lives.

Even after this, he does not ask why he avoids and has been avoiding this truth.

Is writing a memoir, then, purely a record of what happened? A dual chronology of events and emotion? The Scientists might be an example of why a memoir can’t be just that. Why are we given none of those clues that suddenly appear at the very end of the book? Roth spends the book denying his father’s homosexuality over and over, which is not to be faulted as it’s happening — it is forgivable and human — but where is the distance, the reflection about why this happens repeatedly?

“If I have a more-than-ordinary need to relive the past on the page,” writes Roth, “it may be because I have a more-than-ordinary fear of reliving that past elsewhere. My decision to go back through it all, as much as I can remember, was made to remind myself that I can consciously choose to make memoir out of memory.” To make memoir out of memory. This is the same methodology as Birkerts’s wrenching intuition from chaos. Lopate’s double perspective. And when it comes in, at the very end, Roth’s lovely and precise prose goes even further to illuminate the meaning we wait too long to get:

My mother was also being honorable, like the heroine of a stately, aristocratic tragedy by Racine. Even after our traditional family was no longer traditional, she would not have violated the rule, risked bringing about something new. But I was burned out from her noblesse.

In an old essay for Tablet, Roth covers the same subject: his father’s denied homosexuality and literary obsession, as a balm for the pain of hiding his true self — his “textuality.” I found myself missing the Roth of that essay, one whose dorky charm and clear acknowledgement of the truth, from the first sentence, counterbalance his, well, pretention. (If you ever plan on reading Oblomov, by the way, you should probably skip this book as there is a Sparknotes-like, ten-plus page play-by-play of the entire plot.)

Let’s backtrack for a minute. We’ve established, with the help of our friends Neil Genzlinger and Lorrie Moore, that therapy is bad. Not for life, of course, but in writing. It is a truth universally acknowledged that any book written as therapy, or, “to get it all out,” will be not just bad, but boring. Writers often acknowledge this fault of the genre before embarking on a memoir. Take, for example, Benjamin Anastas. In his highly-praised first novel, An Underachiever’s Diary, the protagonist writes, “Please, do not confuse this diary with a memoir written for a therapeutic purpose, designed to exorcise my demons and provide a thrill for everyone who cares to watch them all take flight […]”

Mercifully Anastas’s memoir Too Good to Be True does not grate of discarded therapy sessions and self-help realizations. A survivor of extreme childhood therapy, he’s straightforward about his “mistrust of mental health professionals” and does not sugarcoat or over-intellectualize the human shortcomings that have caused him to fall from toasted literary wunderkind to a failed novelist struggling through massive debt. From the first sentence he has “failed.”

Where Roth grew up on the Upper West Side as the son of a pianist and a scientist, Anastas spent his earliest childhood on a Gestalt-therapy commune where he wandered around the grounds with a sign hanging around his neck: “Too Good To Be True.” His parents later divorce and his father spends his free time mooning friends in the A&P parking lot. Anastas seems as comfortable in failure as Roth does in denial, but as Anastas himself writes, “How else can you explain waking up in a life that has come to resemble its earliest beginnings? That’s what life wants: symmetry.”

Of course a lot happens in the middle. Unlike both Roth and Rushdie, Anastas turns what was once guilt over a crumbled marriage into insight, charting his manipulations and the pettiness that unavoidably comes with being human. He is no hero, though he has much to overcome, some of which he does and some he doesn’t. The opening pages find Anastas spreading himself prostrate on the doors of a Brooklyn church, the Nabokovian “farting” of bus hydraulics in the background. Because he lays out his desperation at the start, there is a simple and natural arc. His pregnant wife left him for another man, “the Nominee”— a this-means-war sobriquet if ever there was one — and he’s got to pull it together if he’s to be a father to his son, keep a new girlfriend, and write another book. Anastas’s humor and self-deprecation put you on his side, make it easy to forgive the failures he so readily cops to:

I lost my wife in a glass elevator at the Hilton in Frankfurt, Germany. Never mind that I hadn’t exchanged my wedding vows with Marina yet, or tried on the ring that she had engraved with the prophetically impersonal message YOU ARE LOVED. Never mind that Marina wasn’t in the elevator with me or even in the same country when I pressed the button to my floor and felt the car start to rise into the upper reaches of the hotel atrium — that it wasn’t her face looking up at me for a first and long-awaited kiss […] It’s not as simple as a fling in a foreign country that I thought I could get away with, though it did cross my mind that I would never have to tell another soul about the elevator ride.

Let’s return briefly to the image of the parking-lot flasher. (Very briefly, I promise.) There is a difference between decent and indecent exposure. Anastas’s admissions of infidelity would be boring and pointless were it not for his admission that he confessed to his wife when he could have gotten away with it and, what’s more, the willingness to figure out why he confesses. No doubt there exists more than a hint of exhibitionism in people who make out in glass elevators. (Bravado the author picked up in an A&P parking lot?) But it is a focused and curious confession, not one “jumbled” as Moore so loathes.

And how can we forget William Gass’s attack on the genre? In the opening lines of his Harper’s essay “The Art of Self” he lectures, “Self-absorption is the principal preoccupation of our age.” This, in 1994.

Gass, at least, critiques with more personality than Genzlinger:

Look, Ma, I’m breathing. See me take my initial toddle, use the potty, scratch my sister, win spin the bottle. Gee whiz, my first adultery — what a guy! That surely deserves a commemorative marker on the superhighway of my life. So now I’m writing my own sweet history.

Look, Ma, let’s cool it for just a sec. “Here’s a rub,” to quote Gass quoting: People are no more indiscreet than ever, nor are these renewed popular assaults novel. In Memoir: A History, exactly what it sounds like, Ben Yagoda marks St. Augustine’s Confessions as memoir zero, published in 398 AD. In 1828, the writer-critic John Lockhart lambasted the genre in an essay reviewing ten memoirs from the previous year: “Cabin boys and drummers are busy with their commentaries […] Thanks to the ‘march of intellect,’ we are already rich in the autobiography of pickpockets.”

The impulse to divulge, to confess, has been documented in memoir since at least the fourth century, and the haters have been around for nearly as long. Indiscretion is not new, but the tether between fleeting, mundane thought and public outlet shrinks faster with ubiquitous, near-requisite social networks like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc. We are just more exposed to other people’s exposures, and our collective patience for frivolity wears thin because of this barrage. An optimist might suggest that such cultural impatience will ultimately weed out the extra-insipid first-person narratives. (An optimist without internet, in any case.)

Nabokov offers another reason to write memoir: as a kind of time travel. “I confess I do not believe in time,” he writes in Speak, Memory.

I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another. Let visitors trip. And the highest enjoyment of timelessness in a landscape selected at random — is when I stand among rare butterflies and their food, plants. This is ecstasy, and behind the ecstasy is something else, which is hard to explain. It is like a momentary vacuum into which rushes all that I love. A sense of oneness with sun and stone. A thrill of gratitude to whom it may concern — to the contrapuntal genius of human fate or to tender ghosts humoring a lucky mortal.

In Nabokov we observe, too, another caste of memoirist: the expatriate. Speak, Memory is of course there with many others, including Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family, a memoir of his childhood in Sri Lanka told in magical, jewel-toned prose:

“You must get this book right,” my brother tells me. “You can only write it once.” But the book again is incomplete. In the end all your children move among the scattered acts and memories with no more clues. Not that we ever thought we would be able to fully understand you. Love is often enough, towards your stadium of small things.

Ondaatje writes not to celebrate a dully romanticized paradise lost, but toward a homesickness that is more complex and throbs keenly, keeping a reader at heartbroken attention.

Carmen Bugan’s Burying the Typewriter falls among these outsider memoirs. She writes to recapture a place lost, but it is certainly no fairytale, despite the marzipan-sweet Eastern European village she grows up in with her grandparents. In the village, her grandfather drinks homemade plum brandy, ?uic?, the grandmother makes cozona, “the best sweet bread in the world,” and during holiday meals, they make Bird Milk dessert and feast on a roast pig that Carmen and her cousins ride “like cowboys” before it is spitted. We know that her romanticizing is at least in part an illusion — that her memories, like frost on glass, have crystallized in pretty shapes.

The young Carmen and her sister suspect their father, a Radio Free Europe listener, of political dissent; they follow him around like characters from a Gombrowitz novel and stage an intervention of sorts, asking him not to distribute anything dangerous. Carmen watches a reality TV segment on the state-run news where Romanian Communist Party comrades confront people suspected of hoarding food to keep from starving between rations: “Comrades, we are here to investigate the pantry of this family in order to show our great nation why there is no food to satisfy all the rations we are so generously allocated and we work so diligently for in our great factories.”

When her father is arrested for distributing anti-regime flyers in Bucharest, which he typed on the family’s secret typewriter, called Erika, Bugan is interrogated by the state police for the first time at the age of 12. She nearly starves to death and is made to stand in class as her history teacher reports that her father is a “mentally ill criminal.” The police find Erika buried in the yard, and a Nabokovian pattern repeats in Bugan’s life.

It’s a pattern I’ve noticed in memoirs — the good ones, anyway: literature as the great escape. For Nabokov, Mary Karr, Michael Ondaatje, Tobias Wolff, Frank Conroy. For Rushdie, Roth, and Anastas, too. Roth rediscovers his dead father through books. Rushdie writes to keep himself sane in hiding. Anastas writes to give himself hope. And Bugan is the most literal, by far. It is her literature teacher who secretly feeds her at school, pretending to punish her in front of the other comrades while keeping her alive. She writes, “I can show no gratitude except by eating her food. With time, she will become the reason I believe that literature truly nourishes the hungry.”

If most memoirs are born out of a love for literature, conceived when a good book (or even a bad one) was the only link to anywhere but here, then why is it so hard for the genre to transcend its second-class status in the literary canon? Has it become a lesser form? Was it always? Lorrie Moore expresses concern that young writers, these days, start out with a memoir and then expect to make a writing life from there. Kierkegaard wrote that “life must be understood backwards,” but “lived forward.” Is there a fixed age one must reach to be capable of both? Are young writers, like Roth, missing the mark because Birkerts’s “intuition of meaning” has not had time to form, or rather, to be shaped by the inescapable battering the psyche takes in the normal course of life, love, and failure? I wonder what tone The Scientists would take were it written ten years down the line.

And yet.

Memoirs are easier to sell, more marketable. James Frey will attest to both of those facts. Yagoda quotes Nielson Bookscan as marking a 400% increase in the number of memoirs published since 2004. What must poor Mr. Gass be thinking about all these self-published memoirs that are just appearing? It does seem to be a starter-form, of starter-content, for writers just starting out.

In Nabokov’s biography of Gogol, he writes:

It is strange, the morbid inclination we have to derive satisfaction from the fact (generally false and always irrelevant) that a work of art is traceable to a “true story.” Is it because we begin to respect ourselves more when we learn that the writer, just like ourselves, was not clever enough to make up a story himself? Or is something added to the poor strength of our imagination when we know that a tangible fact is at the base of the “fiction” we mysteriously despise? Or taken all in all, have we here that adoration of the truth which makes little children ask the story-teller “Did it really happen?” and prevented old Tolstoy in his hyperethical stage from trespassing upon the rights of the deity and creating, as God creates, perfectly imaginary people?

Fiction, even the most mundane, will always burn more romantic than nonfiction; because it hasn’t happened (even the semiautobiographical kind), it belongs more to imagination than a memoir ever could. Love is a kind of ownership, even if it is not always fashionable to acknowledge it as such. We feel proprietary of our favorite books, just as we do our favorite bands — never mind our lovers — even if rationally we know that the ownership is an illusion. So then the task of the memoir writer is doubly hard: not just to write a good book, but to bestow onto the reader possession of her own life. Just as falling in love requires imagination, so reading is an act of faith. When I crack open the spine of a new book, I am putting a basic kind of trust in the author. That she will entertain me. That, by the end, I will know myself better. That her honesty will be hedged with art. That she will let me have her realizations.

Both love and faith go down easier with a little nudging, a bit of cajoling. Getting back to Tolstoy — don’t all roads lead back to him? Let us not forget his finding-religion memoir A Confession — the playwright and critic Julian Marks once quipped, “It has been said that a careful reading of Anna Karenina, if it teaches you nothing else, will teach you how to make strawberry jam.”

Why write a memoir? Well, why write anything, if that’s how you feel. Let us all retire to the nearest dacha and live out our days making strawberry jam. Then we can write our memoirs about the experience. Our “sweet histories.” A few of them will be pretty good.