Did a hack conservative judge just lay the groundwork for the end of the filibuster? It’s very possible. At least, if the Supreme Court goes along — and if Democrats, as they should, fight back. The road begins not with last week’s D.C. Circuit Court decision, which, if upheld, would knock out virtually all recess appointments, but with the Senate Republican plan that Brookings scholar Tom Mann has called “a modern form of nullification.” That was a scheme to prevent some government agencies — the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the new Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB), and others — from functioning by blockading any presidential appointments, using the filibuster to require 60 votes and then keeping the Republican Senate conference united against any nominee. In the case of the NLRB, blocking appointments would mean there was no quorum to do (any) business; leaving the CFPB leaderless would stop the agency from carrying out many of its responsibilities. In both cases, the effect was not only to undermine a Democratic president and Senate, but to bring Republicans something they might not have been able to achieve even if they controlled the White House and Congress: de facto repeal of legislation establishing government regulatory agencies.

Did a hack conservative judge just lay the groundwork for the end of the filibuster? It’s very possible. At least, if the Supreme Court goes along — and if Democrats, as they should, fight back. The road begins not with last week’s D.C. Circuit Court decision, which, if upheld, would knock out virtually all recess appointments, but with the Senate Republican plan that Brookings scholar Tom Mann has called “a modern form of nullification.” That was a scheme to prevent some government agencies — the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the new Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB), and others — from functioning by blockading any presidential appointments, using the filibuster to require 60 votes and then keeping the Republican Senate conference united against any nominee. In the case of the NLRB, blocking appointments would mean there was no quorum to do (any) business; leaving the CFPB leaderless would stop the agency from carrying out many of its responsibilities. In both cases, the effect was not only to undermine a Democratic president and Senate, but to bring Republicans something they might not have been able to achieve even if they controlled the White House and Congress: de facto repeal of legislation establishing government regulatory agencies.

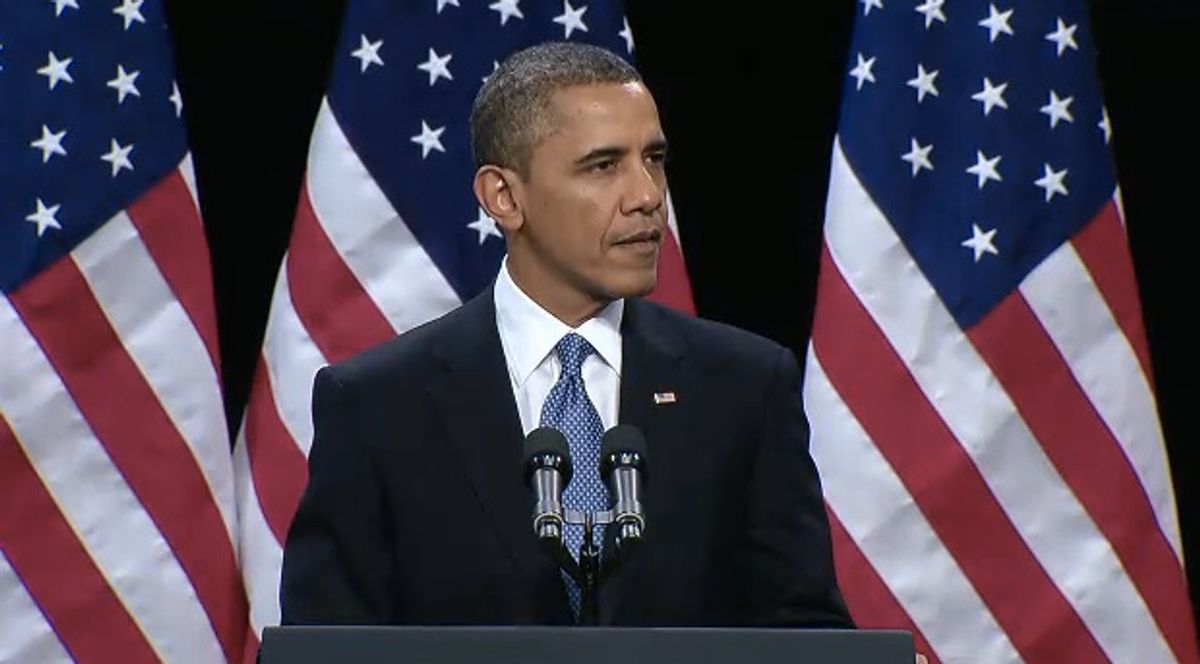

Given that unprecedented provocation, Barack Obama used the recess appointment power to put Richard Cordray at the CFPB and, in the appointments which led to last week’s court decision, to fill vacancies on the NLRB. Obama had been inexplicably reluctant to use recess appointments, making far fewer than either George W. Bush or Bill Clinton. But this wasn’t a situation that could be resolved through submitting a different, perhaps less provocative choice; Republicans clearly intended to block any possible selection. So the appointments went forward.

Until, that is, the D.C. Circuit, in a breathtaking opinion, decided to do away with recess appointments altogether. The court ruled that the practice of recess appointments dating back to the 19th century had got it all wrong; henceforth, recess appointments would only be allowed during the brief interval between different sessions of Congress — as opposed to intrasession recesses — and only for vacancies which opened during that same recess.

Now, that decision was poorly grounded in law and precedent; in fact, as the Prospect’s Scott Lemieux has explained, its “arguments … read like a cruel parody of originalism.” The court claimed that the framers clearly meant to allow only intersession recesses based on the evidence that early presidents did not take advantage of intrasession recesses, glossing over the fact that there were no significant intrasession recesses in the early days of the Republic.

There’s at least a fair chance that the Supreme Court will overturn this one. But there’s plenty of room for a creative ruling by the Court that wouldn’t go nearly as far as the D.C. Circuit attempted, but would still make it impossible for Obama to use recess appointments for the remainder of his term.

So the real question is: What should Obama and the Democrats do in return?

The answer is pretty simple. They won the 2012 elections; if Republicans are willing to bust through the normal workings of the courts and the Senate in order to prevent the government from working with Democrats in office, then Democrats really have only one logical response: to threaten to eliminate supermajority requirements for, at least, executive branch confirmations.

As it happens, the use of filibusters to enforce a 60-vote requirement is brand new, going back in most cases only to January 2009. Recall that Attorney General John Ashcroft was confirmed in 2001 by a 58-42 margin, with Democrats choosing to lose instead of filibustering. And the case for confirmation of executive branch nominees by a simple majority is very strong, regardless of what one thinks about legislation and lifetime judicial appointments. But at the very least, Democrats really have to draw a line: Republicans may filibuster individual nominees, but the attempted nullification of entire agencies will be shut down by rapid, effective reform.

Can the Senate do that? Yup. Despite what you may have heard, majority-imposed Senate reform can actually happen at any point, not just on the first day of a session. The parliamentary mechanisms necessary to do it are obscure, and the precedent set might make other majority-imposed reform a lot easier in the future, but the bottom line is that any time the majority really wants to change the Senate, they can.

The key question, however, is whether Barack Obama would step up and push for it. The truth is that it’s the president who has the most at stake in this fight. Senate Democrats are cross-pressured: As partisans, they might be inclined to fight against Republicans, but as Senators, they might be tempted to support a court decision that shifts influence away from the White House.

But if the president goes to bat, it will turn into a partisan fight, with Democratic-aligned interest groups rallying to his side. The result is either reform or Republican surrender: If Republicans are convinced that Obama and the Democrats are serious, they may decide it’s better to give up on nullification so that they can retain their ability to block nominees at least some of the time.

The new nullification, whether by Republicans in the Senate minority, Republicans in the House majority, or hack appellate judges, is an anti-democratic disgrace. But that’s what’s going to happen should the Supreme Court side with the D.C. Circuit — unless Democrats fight back. Obama, Harry Reid, and the 54 other Democratic Senators have a responsibility to do so.

Shares