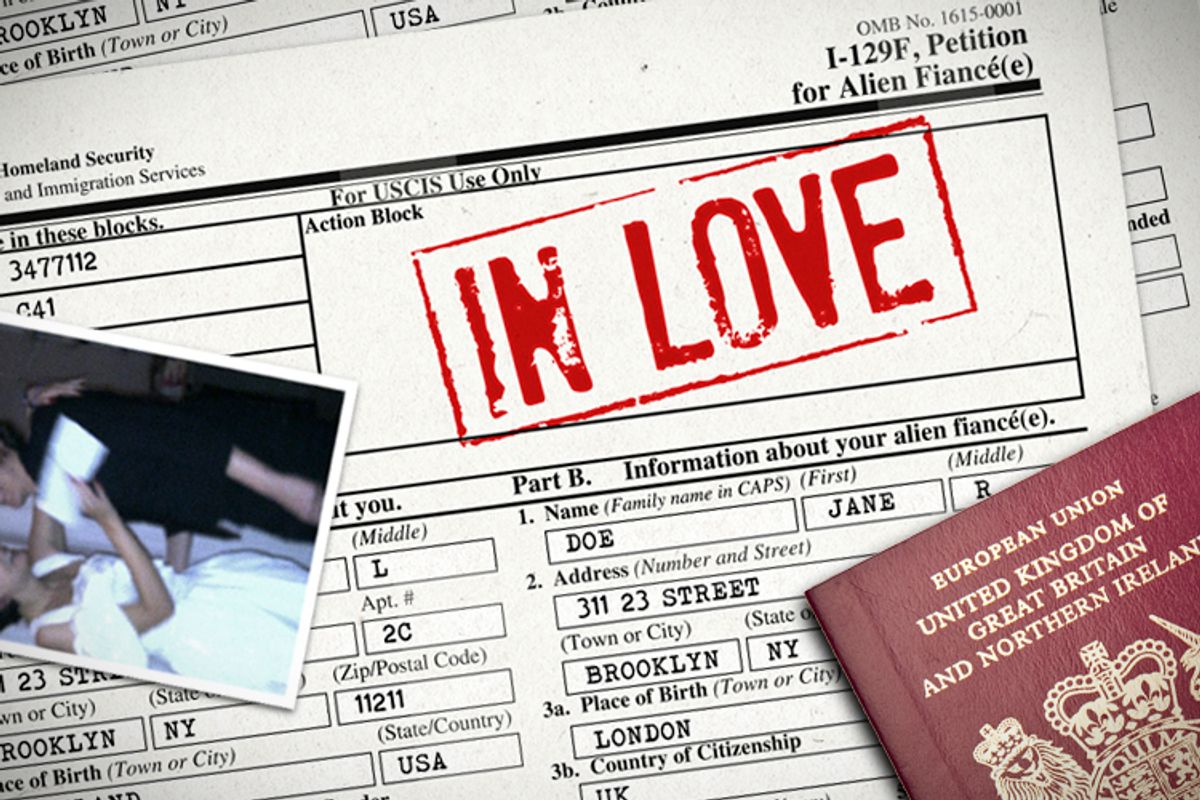

Raised a denizen of the Internet, I don't have a lot of hard-copy photographs. I only own one photo album and it's tucked away in a box file on a shelf that I can't even reach. I've rarely looked at the crimson binder of amateur snapshots -- my wedding album -- lovingly compiled for the perusing eyes of a federal agent.

I don't have a green card marriage. I do have a marriage green card. The process to get it, as anyone who has gone through it might attest, was a dizzying, panic-inducing bureaucratic obstacle course; a strange lesson in state determinations of love and partnership.

A New York Daily News article last year about the officials who interrogate couples applying for green cards noted, "The green-card gumshoes use old-fashioned sleuthing to ferret out marriages of convenience from cases of true love." But in my experience, "true love" as recognized by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is an uncomfortable act to perform.

Some background: I moved from London to New York in 2009 on a student visa for graduate school in journalism. When I met my partner that winter while reporting on New York City's beleaguered squat scene, I had an internship lined up back in England for the following summer and every intention of returning "home." The first night I slept next to him, on a dusty hardwood floor in an abandoned Bedford Stuyvesant brownstone, we didn't touch but to share the earbuds of my iPod. We touched again soon after.

"How did you meet?" the terse woman at the USCIS asked my partner at our green card interview in early 2012, a few months after our wedding.

"In a meeting," he replied, before pausing for what felt like too long. "A meeting with a homelessness charity. She was reporting," he added, rendered awkward and abrupt by an unease with authority that permeates to his marrow.

Proof of love when it comes to green cards is something both specific and ephemeral. The idea is to show, as our immigration lawyer explained, not only that you love each other and want to be together in this country, but that you would have gotten married anyway. It's an important hypothetical, which technically gives the government insurmountable leverage. Proving what you would have done anyway is impossible, and this is the catch. The possible world in which borders and governments don't threaten to tear people who love each other apart is too far from this one to speculate over. I don't know what I might do there. What place marriage would have in such a world is another question entirely.

Most couples pass muster when it comes to the would have done it anywaycondition. In 2011, 270,761 couples applied for green cards through marriage and only 7,290 were denied. But what gets to count as proof?

When amassing evidence of love for the USCIS, a couple essentially aims for a facsimile of doing what people who get married anyway do -- which, going by government guidelines, refers to anachronistic, income-stable, middle-class American Dream aspirants. Such people barely exist among all-American couples, let alone green card hopefuls, but the simulation persists between the lines of USCIS guidelines for proof.

The best proof of "true love" you can give in order to stay in America as a married couple is a child together (existent or forthcoming), so long as the green card applicant first entered the U.S. legally. Proof of joint property ownership is also recognized as a mark of "true love." My partner and I don't want children; and even if the notion didn't offend, we couldn't afford property anyway.

My partner and I began living together soon after we met, but we've never signed a lease together. We've shared beds, rooms, whole apartments, for months and weeks in Manhattan, Brooklyn and (for a drab nine months) in D.C. Paychecks and bank statements went to a spread of friends' houses and old addresses. We've barely spent a night apart in three years, but we lacked the records to prove it. Following our lawyer's advice, we opened a joint bank account and ensured mail was delivered with both our names to our current abode -- a Clinton Hill two-bedroom we share with our best friend, whom we love as much as each other. Precarious living and proof of "true love" sit at odds.

Rom-com depictions could lead one to believe that green card interviews deal in the important banalities of living and loving together. How does he like his tea? (Black if not elaborately herbal.) What TV shows do you watch? (All of them.) But during briefings with our lawyer, we learned that a whole different field of knowledge would be expected (if not always called upon) at our interview and the terrain is contoured anachronistically around the traditional family.

My partner will likely never meet my biological father; we hardly speak. I will never meet his parents -- they're characters to me in his rarely told stories from a difficult Arkansas upbringing. But I learned their names for the green card; he learned Daddy's proper name too. My mother's legal name is Selena, but she's been Sindy to everyone since she was a baby.

My elegant mother, who never imagined her Cambridge scholar daughter getting married in a Bushwick warehouse, wearing Doc Martens and uttering the vows "for poorer and poorer still," but who stood with us that night, raised a plastic glass, toasted to our love and meant it -- that woman is Sindy. "Her real name's actually Selena," I informed my partner, who loves Sindy, in the lawyer's office. The dissonance between intimacy and legal fact felt stark.

Our green card interview went smoothly. We had been a little concerned -- Ihad been arrested a few months earlier while reporting when Occupy stormed the Brooklyn Bridge, and my partner has what you might call an active history of dissent. My charges were dismissed by a judge, but paranoia prevails when so much is at stake. (My partner doesn't have a passport currently; I still fear flying across the Atlantic, just in case, for some reason, I can't get back.)

In a typical federal building in downtown Manhattan with a gleaming glass and marble entrance hall, and cheerless offices above, my blood ran cold as we were shown to a floor usually reserved for special cases. It may have just been because my husband is nearly 12 years older than me and that counts as an abnormality -- we'll never know. But, crimson wedding album and paperwork in hand, we answered questions about siblings and parents and birthdays and jobs. No enhanced interrogation, but our answers had required learning.

Of course, I don't want the government to demand more intimate knowledge about our relationships. I don't want to tell a federal agent that I know my partner prefers bourbon to scotch. Or that he thinks Max Stirner deserves a fairer shake. Or that the tattoo of a spidery tree etched across his freckle-flecked shoulder depicts a certain Spanish moss in Gainesville, which meant a lot to him in a different time. Or that we're not monogamous, but it's complicated. Or that he always puts too much hot sauce on his food and always burns his mouth. Or that he wore a hat every day for two years until he lost it in a scuffle with the police and never replaced it. Or that our pet names hail from NBC shows. All these nuggets I know from a life shared -- knowing my husband's parents' names is not part of that.

A New York-based white couple, one male, one female, with the green card applicant from Britain, rarely run the immigration gauntlet. This is not a story about enduring persecution. This is merely a Valentine's Day reflection on state-sanctioned guidelines for proving true love. Own property, have children, have stable addresses and jobs and stories to tell. Know each other's extended families. Know birthdays and phone numbers, even if you hate birthdays, even if you hate the phone. Keep a photo album, hard copy.

Shares