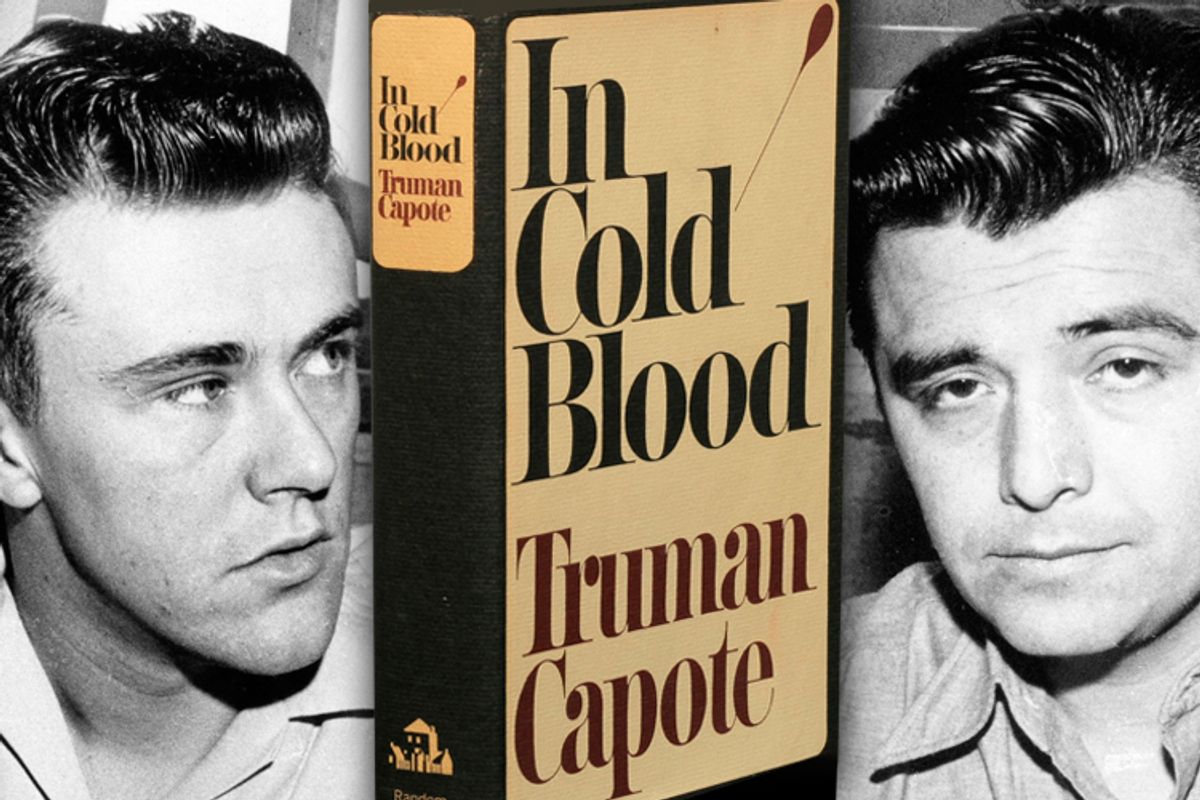

Questions about the accuracy of "In Cold Blood," the seminal 1966 "nonfiction novel" by Truman Capote, are nothing new; they bubbled up as soon as the book was published. Capote himself — who always maintained that "In Cold Blood" was "immaculately factual" — made thousands of changes (some grammatical, some factual) to the true-crime classic between its initial four-part-serial publication in the New Yorker and its appearance in book form the next year. His sources and critics have challenged aspects of the text ranging from the price of a horse to whether or not a graveside conversation that appears in the book's concluding pages ever occurred.

Two recent developments, however, shed a particularly troubling light on Capote's account of the 1959 murders of four members of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kan. They pertain to the search for the crime's perpetrators, Richard Hickock and Perry Smith, and to an additional four murders they are suspected of committing. In the first development, the Wall Street Journal recently reported on a dispute over records of the investigation. These documents, currently in the possession of Ron Nye, were taken home years ago by his late father, Harold Nye, one of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation detectives assigned to the case.

Some background: For 19 days after the Clutters' bodies were discovered on Nov. 15, the KBI and its lead investigator, Alvin Dewey, who serves as the hero of Capote's book, had been stymied. Then, on Dec. 4, a prison informant reported that he had heard Hickock, a former cellmate, describe his plan to rob the Clutter house, a plan that included the killing of any and all witnesses. According to Capote's version of events, the KBI immediately sent Nye to question Hickock's parents on the pretense that he was looking into Hickock's parole violations. In their home, Nye spotted a 12-gauge shotgun belonging to Hickock, the same type of gun used in the killings. This interview solidified the KBI's belief that Hickock and Smith were likely suspects.

The cache of documents, which the KBI is suing to recover, instead indicates that investigators did not visit the Hickocks until five days after receiving the informant's tip. Why the delay? The prosecutor in the case, a longtime critic of "In Cold Blood," has always maintained that Dewey initially refused to consider the two men because they did not match his theory of the killings. "Dewey was convinced it was somebody local who had a grudge against Herb Clutter," the prosecutor, Duane West, told the Journal.

The Journal article goes on to observe that Dewey's short-lived reluctance to pursue the lead resulted in "no delay of justice. Within five months of killing the Clutters, Messrs. Smith and Hickock were caught, convicted and sentenced to death. Both men confessed. They were hanged in 1965." This becomes, then, a story about a writer's willingness to bend the truth a bit in order to burnish the image of his own story's hero. There may have been reciprocity involved. Dewey, as the Journal article details, provided Capote with essential help in the research of "In Cold Blood"; for instance, Dewey persuaded several sources to grant interviews to the writer.

But what if Dewey's hesitation to abandon his conception of the crime had graver consequences? In a separate development, Kimberly McGath, a detective in the Sarasota County Sheriff's Office in Florida, is even now awaiting the results of DNA tests. Those tests, she hopes, will confirm her suspicion that Hickock and Smith were also guilty of murdering the Walkers, a family of four living in the town of Osprey, Fla.

The Walkers -- a husband and wife in their early 20s and their two small children -- were shot to death on Dec. 19, 1959. The killings occurred during the six weeks between the Clutter murders and Dec. 30, when Hickock and Smith were picked up by police in Las Vegas. If the KBI did delay in following up on the lead, and Hickock and Smith did kill the Walkers, how pivotal was the time lost by the investigation? If the KBI had looked into the lead immediately, as Capote depicts them doing, could they have saved the Walkers' lives?

By strict chronology, evidently not. If, one way or another, it was going to take 26 days (from the day the lead was first pursued to the arrest) to apprehend the killers, then Hickock and Smith would have still been at large on Dec. 19, whether or not someone had been sent to interview Hickock's parents immediately. But criminal investigations, like any other human activity, do not proceed in such a fashion.

Hickock and Smith, by their own account, traveled 10,000 miles (including a jaunt through Mexico) after the Clutter murders. They were known to be in Florida around the time of the Walker murders, but provided an alibi for Dec. 19 and passed a polygraph test asking them about it. In "In Cold Blood," Capote depicts Smith as marveling over a newspaper story about the crime that so closely resembled the Clutter murders, perpetrated not far from the hotel where they had stayed in Tallahassee. However, Florida investigators later discovered no support for the men's alibi and experts dismissed the polygraph evidence as primitive and unreliable. There is evidence that Hickock and Smith arrived in Florida three days before the Walker murders, and no evidence of their whereabouts on the night of the murders.

At some point before they drove to Florida, Hickock and Smith spent some days in Kansas City, raising money by passing bad checks, a Hickock specialty. Capote depicts Dewey as agonizing over this period, which his wife describes as "the week before Christmas," during which the killers "came and went without getting caught." In fact, if the Florida investigators are correct, Hickock and Smith arrived in Pensacola, Fla., on Dec. 16, nine days before Christmas. In any case, had they been caught in Kansas City, the two men would not have made it to Florida at all.

Although most of the pair's movements after the Clutter murders would have been hard to trace, Kansas City was different. Hickock, whose parents lived in the area, contacted several old friends and acquaintances there; these were the people who cashed his "hot paper." A salesman from whom he'd bought a TV wrote down the license plate of the stolen car Hickock was driving. It's possible that if authorities had begun to take the two men seriously as suspects on Dec. 4, rather than Dec. 9, the five additional days would have left them better prepared to capture the killers (and perhaps more certain of their guilt) when they resurfaced in Hickock's old stomping grounds. The public, for example, hadn't been told that the two men were being sought in connection with the Clutter murders because Dewey still felt they could be innocent. (On the other hand, even if they weren't, he also thought he had a better chance of jolting a confession out of one of them -- once he finally caught them -- if they didn't realize they'd already been fingered for the murders.)

There's no reason to conclude that Capote or anyone else was deliberately covering up evidence that Hickock and Smith had indeed had the opportunity to commit the Walker murders. Chances are, if Capote fudged the account of how quickly the KBI acted after receiving that decisive tip, the author did it because he thought the detail didn't matter much. Capote does portray Dewey as wedded to the (erroneous) idea that the Clutters were killed by someone they knew, but the writer might have decided -- whether as a favor to a source who had done a lot for him or to make a better story -- to downplay how much Dewey allowed that belief to shape his investigation.

In the many recent controversies over falsehoods and exaggerations in nonfiction articles and books, it's usually the author's desire to tell a more conventionally satisfying story that gets the blame. It's more heartrending if the reporter has actually met the victims of workplace poisoning face-to-face and more exciting if the addiction memoirist demonstrated his commitment to sobriety by undergoing a root canal without anesthesia. Less discussed is the reporter's sometimes perilous dependence on his or her sources. The person who helps the most is often the one whose version of the story gets the most prominent play. A journalist who contradicts a major source's version risks being accused of betrayal and misrepresentation by someone who may have come to seem like a friend.

Joan Didion, that master of nonfiction, famously remarked, "Writers are always selling somebody out." This is especially true when it comes to the sort of in-depth, intimate reporting Capote practiced in "In Cold Blood." A seemingly unimportant, if unflattering detail, like a good investigator's slow response to a lead that doesn't support his favored theory of the crime, may turn out to have unanticipated significance.

Kansas authorities have agreed to analyze DNA from the bodies of Hickock and Smith to compare with DNA evidence found at the Walker crime scene. Cold cases are a low priority, so no one knows how long it will take for the results to come through. But we don't need those results to tell us who it was that Capote sold out; it was his readers.

Further reading

Shannon McFarland's extensive article for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune on the Walker murders and their possible connection to Richard Hickock and Perry Smith

McFarland on the discrepancies between "In Cold Blood" and the findings of Florida detectives

Kevin Helliker for the Wall Street Journal on recently uncovered documents about the investigation of the Clutter murders

Jack de Bellis on the changes Truman Capote made to "In Cold Blood" between its publication in the New Yorker and its publication as a book

Shares