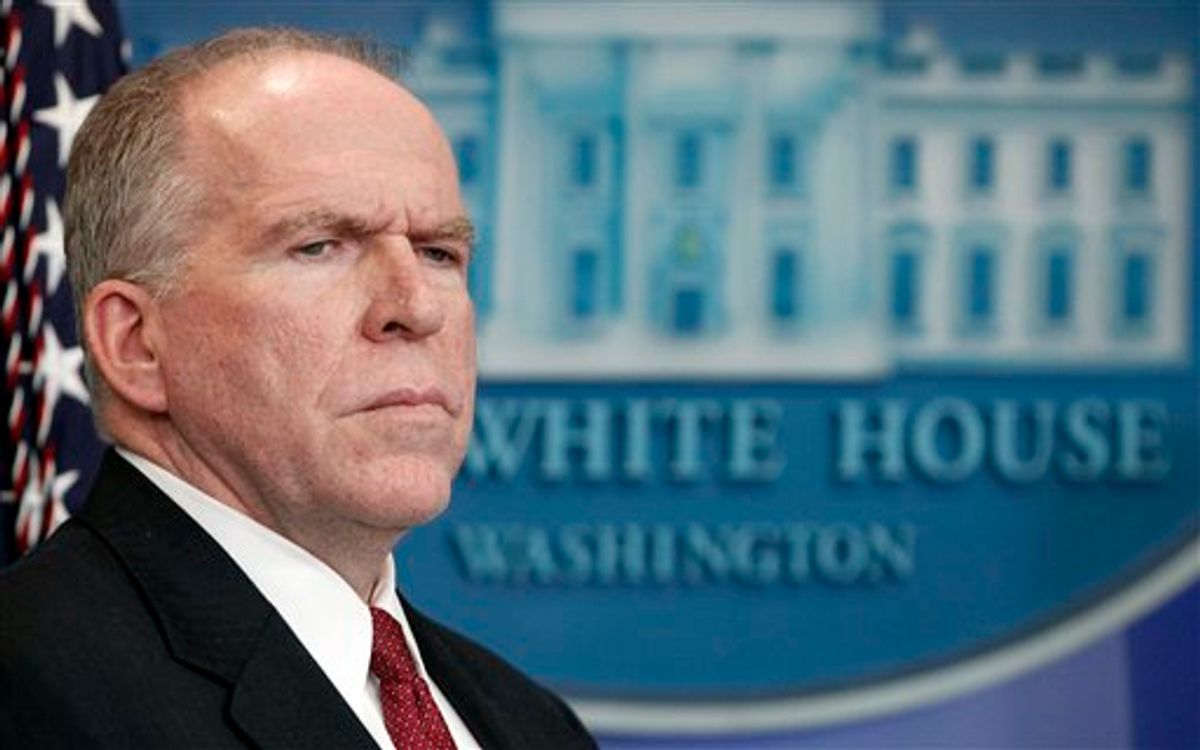

At John Brennan’s confirmation hearing to be director of the CIA earlier this month, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., asked him whether the administration could let the public know under what circumstances the government believes it can kill Americans within the United States. The exchange takes on added resonance today, as new reports reveal the Obama administration continues to hide its targeted killing authority, even from Congress.

“I've asked you how much evidence the president needs to decide that a particular American can be lawfully killed and whether the administration believes that the president can use this authority inside the United States,” Wyden reminded Brennan at the Feb. 7 hearing. ”What do you think needs to be done to ensure that members of the public understand more about when the government thinks it's allowed to kill them, particularly with respect to those two issues: the question of evidence and the authority to use this power within the United States?”

After saying, “What we need to do is optimize transparency on these issues, but at the same time optimize secrecy,” Brennan emphasized that while the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel “establishes the legal boundaries within which [the executive branch] can operate … It doesn't mean that we operate at those outer boundaries.”

Just hours earlier, Wyden had read two Office of Legal Counsel memoranda describing the administration’s authority to carry out the targeted killing of Americans.

Wyden had requested the memos at least five times over the previous two years, and had finally received them by threatening to hold up Brennan’s nomination. He went from reading those memos to asking this question about when the administration believed it could target Americans within the United States.

Wyden’s question, even more than a similar question posed by Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., last week -- "Do you believe that the president has the power to authorize lethal force, such as a drone strike, against a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil?” -- ought to concentrate the public’s focus on the government’s counterterrorism programs.

Paul’s question has elicited a focus on drones, not targeted killing more generally.

At a Google hangout after Paul released his letter and announced a hold on Brennan’s nomination, a participant expressed concern to the president, “that your administration now believes that it is legal to have drone strikes against American citizens. And whether or not that is specifically allowed versus citizens within the United States.” In response, President Obama answered, “First of all, I think, there’s never been a drone used on an American citizen on American soil.”

Similarly, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., asked Brennan, in a follow-up to his hearing, “Could the administration carry out drone strikes inside the United States?”

As Obama had, Brennan emphasized that no drone strikes had been carried out within the United States. “The administration has not carried out drone strikes inside the United States and has no intention of doing so.”

He didn’t answer about targeted killings more generally.

The administration seems happy to answer whether or not anyone has been killed in a drone strike in the United States. No one has yet answered whether targeted killings, conducted via some means other than drones, have ever been carried out. And no one has yet answered whether either the Obama administration or the Bush administration before it ever has operated at the boundaries of what OLC says is possible within the United States.

That’s important because people have died in counterterrorism operations within the United States. As just one example, an African-American Muslim cleric, Imam Luqman Ameen Abdullah, died in an arrest raid in Dearborn, Mich., in October 2009. As with Anwar al-Awlaki — the Yemeni-American cleric killed in Yemen in 2011 in the best-known targeted killing directed against an American — the government claimed Abdullah was a highly placed leader of a radical Islamist group training to conduct jihad against the United States (though much of their evidence consists of his blustery attacks on the United States). The FBI brought a team of 66 FBI agents — 29 in the immediate team — including two K-9 teams, snipers and a master breacher, to arrest Abdullah and four associates.

There’s no reason to believe Abdullah’s death was a targeted killing. The FBI claims it sicced a dog on him because while he was prone on the ground, they claim, he refused to show his hands. And they say he pulled a gun and shot the dog, in response to which they shot him 21 times.

But Abdullah’s death is a reminder that when the United States uses targeted killing overseas, it often as not uses tactical assaults, as in the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, rather than drones.

And it’s not just drone killing that has served as a distraction in this conversation. So, too, has a focus on whether such strikes fit in the Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF) that authorized the Afghan war, passed by Congress in 2001.

Much of the commentary on whether and how the administration could target Americans within the U.S. treats it as a military question — whether, for example, Posse Comitatus (federal law intended to limit the use of military personnel to enforce laws) would prevent the administration from launching military operations to target Americans within the United States.

Paul, too, asked similar questions in his letter to Brennan. “Do you believe that the Posse Comitatus Act, or any other prohibition on the use of the military in domestic law enforcement, would prohibit the use of military hardware and/or personnel in pursuing terrorism suspects — especially those on a targeting list — found to be operating on U.S. soil?”

Wyden, for his part, talks about the military, but repeatedly talks about intelligence agencies — not the military — conducting targeting killing.

Last year he asked for “any and all legal opinions regarding the authority of the president, or individual intelligence agencies, to kill Americans in the course of counterterrorism operations.” And last month, he suggested the executive branch was “claim[ing] that intelligence agencies have the authority to knowing kill American citizens …” At least for Wyden — who has been asking about this authority for two years — it’s an authority the intelligence agencies have used, not the military.

And the authority of intelligence agencies killing Americans would work differently. As Paul notes, the National Security Act, which authorizes the CIA, prohibits “CIA participation in domestic law enforcement." He asks whether that prohibition would “apply to the use of lethal force, especially lethal force directed at an individual on a targeting list, if a U.S. citizen on a targeting list was found to be operating on U.S. soil?”

Members of Congress are asking whether the CIA can operate in the United States to kill Americans. Not by drone, but by any means.

And it’s not just members of Congress trying to exercise some oversight over the administration. Even the white paper the administration wrote in 2011 and released to Congress last year (and publicly last month) stressed its authorities derived not just from the AUMF, authorizing military action, but from the president’s own authority. The white paper actually situates the power to kill Americans in Article II — “The President has authority to respond to the imminent threat posed by al-Qa’ida and its associated forces, arising from his constitutional responsibility to protect the country” — before it mentions “Congress’s authorization of the use of all necessary and appropriate military force against this enemy,” under the AUMF.

The response to the focus on targeted killing last week focused on whether drones, apparently run by the military under the AUMF, could target Americans in the United States. But that’s not the question we should be asking.

The administration continues to hide its targeted killing authority, even from Congress. According to the New York Times today, it aims to avoid turning over seven more memos on targeted killing before Brennan is confirmed. All the more reason to continue to ask about this authority.

Shares