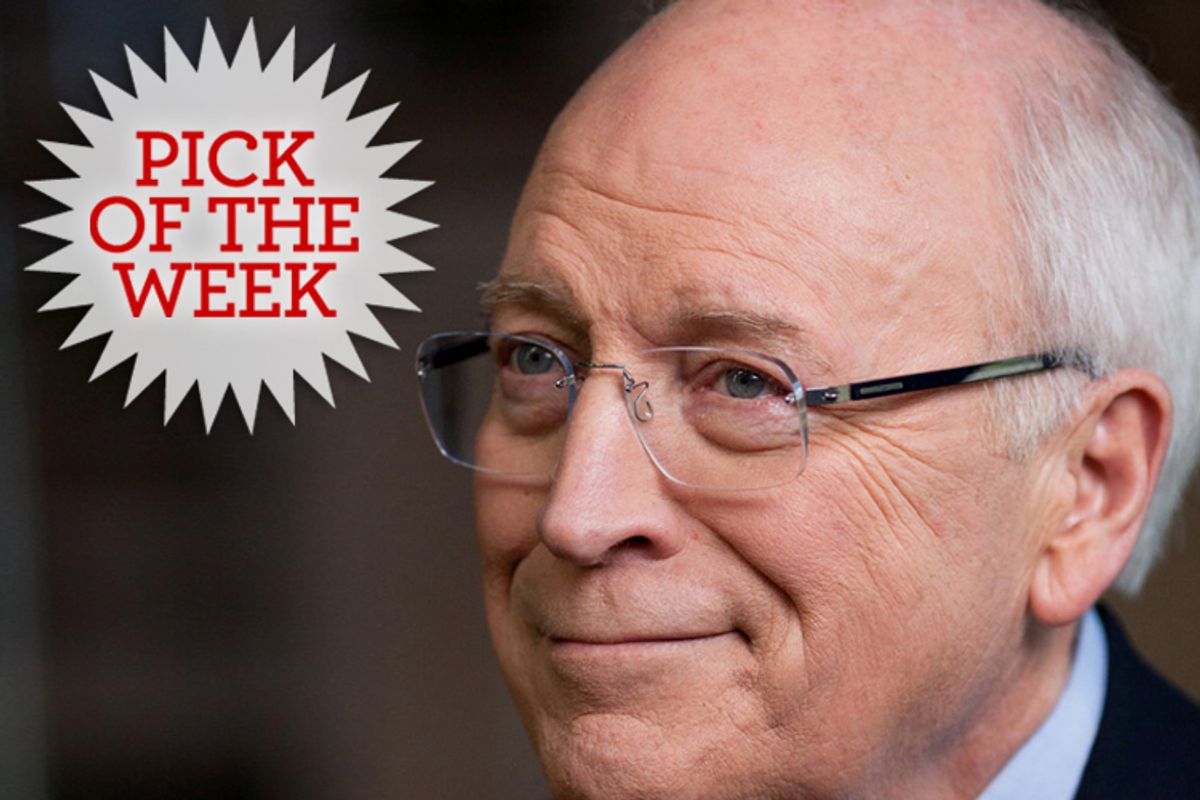

There are so many jaw-dropping moments in “The World According to Dick Cheney” that I’m sure to forget several of them. One comes right at the beginning, when interviewer and co-director R.J. Cutler asks the most “consequential” vice president in American history – that’s Cheney’s word – a series of softball questions to get him warmed up. Cheney looks undeniably older and thinner after his recent heart transplant (talk about jokes that write themselves!), and he does deliver a few minuscule nuggets of warm-and-fuzzy: Happiness is fly-fishing on the Snake River, and misery is the loss of a family member. In case you’ve been wondering, his favorite food is spaghetti. Then Cutler asks Cheney about his biggest flaw. It’s a standard Barbara Walters-style question, for which every skilled politician has a faux-humble answer at the ready.

But Dick Cheney is no ordinary politician. As one commentator observes much later in the film, he may belong in a Venn diagram of one, where Machiavellian political geniuses overlap with ideological zealots. He seems genuinely puzzled by the question, which demands at least the pretense of introspection and cannot be answered with “Waterboarding, hell yeah!” Or at least he’s puzzled about what to say, which may not be quite the same thing. He stares into space for a few seconds and then says, “I don’t spend much time thinking about my flaws. I guess that’s the answer.”

There you have it: Cheney has enough intelligence and self-knowledge to understand that the inability to perceive one’s own flaws is itself a flaw, but no actual interest in the possibility that he may possess other flaws as well. We’re a long way from, say, the terrain of Errol Morris’ Oscar-winning “The Fog of War,” in which Vietnam-era Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, a bona fide Cold War intellectual, engages in far-ranging self-criticism and philosophical rumination.

Some critics have already complained that Cutler spent 20 hours interviewing Cheney about everything from his ne’er-do-well Wyoming youth to the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks – when he placed phone calls to those who came after him in presidential succession, believing that both he and George W. Bush might be “taken out” at any moment – without revealing any chink in the armor, any philosophical explication or scintilla of self-doubt. But that fact is exactly what makes “The World According to Dick Cheney” so fascinating. Cheney’s not some Camelot-style “best and the brightest” girly-man, and he will go to his grave – presuming he turns out to be mortal after all – as the neocon Frank Sinatra who did it his way, completely unrepentant and only sorry that the rest of us are such unbelievable pussies.

Despite the title of the film, Cutler never elicits any grand pronouncements from Cheney about the world, not even the standard-issue American exceptionalism or “clash of civilizations” theory that you might expect. Other than saying that being a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin in 1968, when it was a hotbed of student radicalism, only drove him further to the right, Cheney never discusses his own politics. We do, however, learn where his loyalties lie – first and foremost with Donald Rumsfeld, the friend and mentor he finally overshadowed – and whom he views with disdain. That category seems to include almost everyone in the known world, but notably his former boss, whom he discusses only in distant and diplomatic fashion and almost never by name.

Cutler’s film (which is co-directed and edited by Greg Finton) is conventional in structure, intercutting the face-to-face Cheney segments with talking heads drawn from journalism and academia, file footage, vintage photos and so on. But the extensive portion about the Bush White House is full of gripping material if you’re someone like me, who couldn’t bear reading about the internal dramas of that administration at the time because it all just seemed so odious but realized, after the fact, that it was pretty important. It’s certainly not a new theory that Cheney stacked the executive branch with appointees he trusted, often going two or three levels deep into Cabinet departments, and drove the inexperienced Bush, who knew and cared little about world affairs, toward a hard-right global agenda.

In this reading, which Cutler and Finton fill in with considerable detail, it was Cheney who installed his one-time mentor Rumsfeld in the Pentagon (they first worked together in the Nixon White House – on an anti-poverty program, bizarrely enough), who pushed relentlessly for war with Iraq after 9/11, and who advanced bogus theories about Saddam Hussein’s nonexistent weapons programs and imaginary links to al-Qaida. But the entire Cheney perma-war agenda began to go disastrously south around 2004, with the rise of the Iraqi insurgency, the non-discovery of any WMD and the revelations about Abu Ghraib; a second-term rift opened between Bush and Cheney that has evidently not healed.

At least according to Cutler’s screenplay (co-written with Francis Gasparini and voiced by one-time TV president Dennis Haysbert), Cheney kept Bush in the dark about the warrantless domestic surveillance program that the Justice Department finally decided was illegal, nearly sparking a wave of mass resignations at Justice and a scandal that could easily have sunk Bush’s 2004 reelection campaign. (Second thoughts? None. “I would’ve let them all resign,” says Cheney.) He urged Bush to bomb a Syrian nuclear reactor, at a Cabinet meeting where the president reportedly rolled his eyes and no one else supported the idea. Cheney resisted any shift in military posture in the face of mounting public opposition to the war, and resisted the push to fire Rumsfeld, who became politically toxic after Abu Ghraib. When Bush insisted – perhaps urged by Condoleezza Rice, who became Cheney’s second-term nemesis – Cheney delivered the news to his old boss himself.

That’s about the only time in the whole movie we see him displaying something that looks like genuine emotion. Cheney doesn’t feel bad about killing Iraqis by the thousands for no particular reason, or about ordering the extrajudicial imprisonment and torture of detainees, or about expanding the power of the executive branch to quasi-imperial levels (a development, it must be said, that has been celebrated and embraced by Bush’s successor). He feels bad about firing Don Rumsfeld.

There are so many facets to Cheney’s life and career that you couldn’t get them all into a Showtime miniseries, let alone a single two-hour film, and I don’t blame Cutler for loading up on the dramatic, only-in-America details. Cheney’s political odyssey is literally like no one else’s. Given the parlous state of his cardiac health and the shadowy character of his Halliburton-era finances, he’d never have wound up as Bush’s running mate in 2000 if someone other than him had been running the selection process. A decade before that, he’d been George H.W. Bush’s defense secretary, presiding over Gulf War I – and 15 years before that, he’d been Gerald Ford’s chief of staff at age 34, the youngest person ever to hold that post. And all that despite his evident distaste for interpersonal glad-handing and lack of skill at “retail politics.” (His own 1988 presidential campaign was exceedingly brief.)

Considering that in 1963 Cheney was an unemployed 22-year-old electric-company lineman in Rock Springs, Wyo., serving time for (at least) his second drunk-driving arrest, it’s a difficult tale to comprehend. What drove him from dissolution in the back of beyond (and I’ve been to Rock Springs) to become the Voldemort of American politics, whose very name causes liberals to make the Elder Sign and spit into the dust? Hell, who knows? He may not know himself. I do wish Cutler had asked Cheney more about his views on energy policy and his snuggly relationship to the oil industry – that’s a central aspect of the Cheney worldview, and one that isn’t even mentioned here.

For that matter, I wish Cutler had allowed Cheney to field a few softballs about his unhesitating acceptance of his lesbian daughter, and about the fact that he’s never been interested in the social issues of the Christian right. (If he has any religion other than a faith in power, it’s never come up during his public life.) But maybe the point of “The World According to Dick Cheney” isn’t just that he’s unapologetic about the Iraq invasion and waterboarding and the rest of it, and says he’d do it all again six ways to Sunday. The thing that makes Cheney a hero to the curmudgeonly hard right of a certain generation is precisely his resistance to navel-gazing. You can put him on the couch for 20 hours or 1,000 hours; he won’t tell you diddly squat. (Which might be exactly how he put it to himself.) If loving Donald Rumsfeld is wrong, he doesn’t wanna be right.

“The World According to Dick Cheney” premieres March 15 on Showtime, with repeat broadcasts and home video to follow.

Shares