All eyes this week are on the CPAC meeting of conservatives, a Beltway gathering that will produce the first straw poll of Republican presidential candidates of the 2016 cycle. (Hey, we’re under three years to the Iowa caucuses now!) But the wiseguy reaction should come soon: All of the jockeying for position is irrelevant, because everybody knows that Republicans always select the “next in line” candidate. For example, Micah Cohen claims that Hillary Clinton may benefit from a next in line effect, and that it’s “a dynamic seen in several recent Republican primaries.”

It’s a myth.

But expect to see plenty of it. It was a widely circulated myth during the last cycle, and the nomination of Mitt Romney will surely entrench the myth even more. But still, it’s a myth.

Of course it is true that parties – all parties – are most likely to nominate a candidate who enters the fight as the clear leader. But if “next in line” is more than just a trite statement that strong candidates usually do well, then it doesn’t help to predict anything.

The truth is that “next in line” has really only been tested three times during the modern era of Republican presidential nominations, and it’s only clearly worked once.

Here’s the history.

The modern nomination era began in 1972, when Republicans merely renominated a sitting president. In fact, Republicans have made the obvious choice of nominating an incumbent president in quite a few cycles during the modern era.

In three others, Republicans nominated an obvious choice: sitting Vice President George H.W. Bush in 1988, Ronald Reagan in 1980, and Bob Dole in 1996. Yes, one way of describing those choices would be to say that they were all next in line – each of them had been runner-up in the last contested nomination cycle. But another way is to say that nomination fights aren’t necessarily level playing fields, and that each of these candidates entered with other large advantages. Bush was the sitting V.P. of a president who was extremely popular within the party; of course he won. Reagan in 1980 was the hero of the dominant faction within the party, a third-time candidate; of course he won. Dole is the weakest of the three, but he was also a longtime party leader – former V.P. candidate, former Republican National Committee chairman, current GOP Senate leader. We don’t need his runner-up finish in 1988 to explain his victory in 1996.

That leaves three cases.

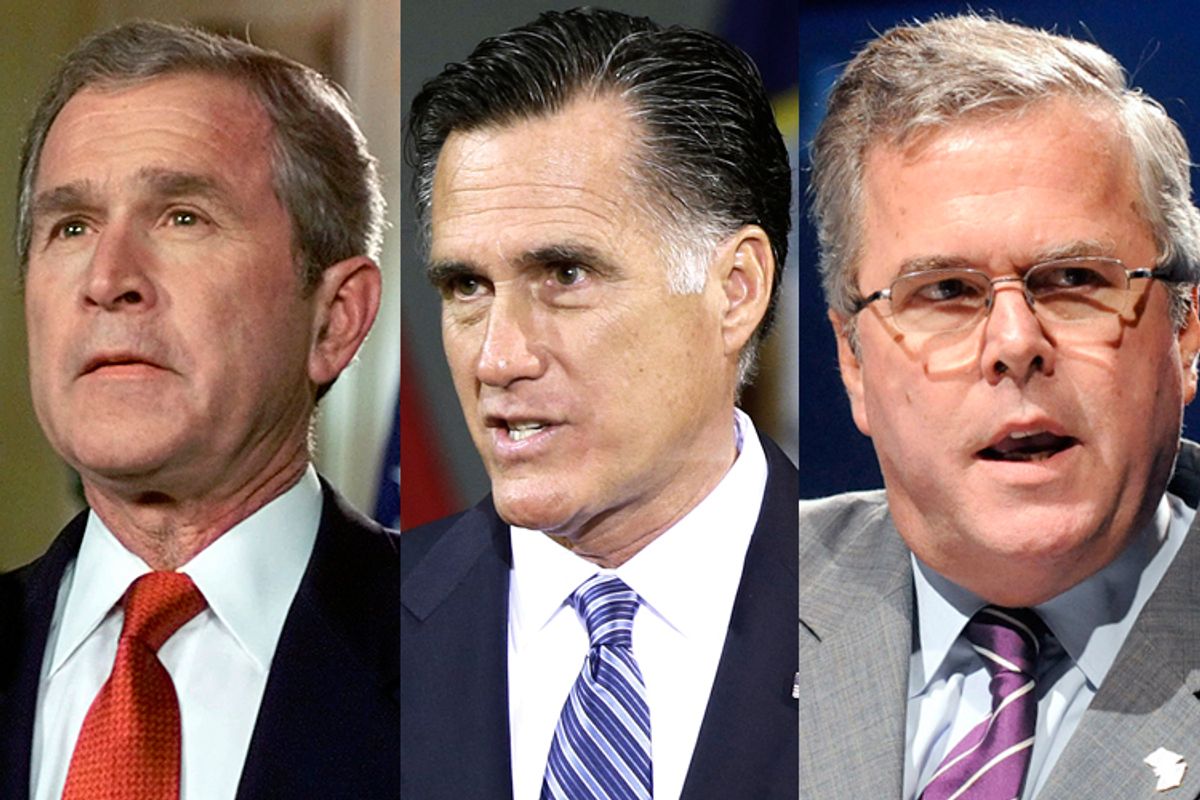

In 2000, the winner wasn’t the runner-up in 1996; it was first-time candidate George W. Bush.

In 2008, the winner was indeed 2000 runner-up John McCain.

And then in 2012, the winner was Mitt Romney. However, Romney wasn’t the runner-up in 2008, or at least not clearly so. Mike Huckabee received slightly more delegates than Romney, although Romney won a few more votes. The Huck also survived a month later than Romney, a meaningful measure given that presidential nomination contests are to some extent questions of survival.

What if we expand the definition of “next in line” beyond simply being the runner-up in the previous round? That might allow Romney to emerge as a more obvious pick, perhaps, and could even account for George W. Bush, right?

Well, no. If we expand it, then we no longer have a meaningful way to define “next in line” and we’re stuck with something that can’t really predict anything. That is, if George W. Bush was plausibly “next in line” in 2000 … then why wasn’t Jeb Bush next in line in 2008 and 2012? Or for that matter, Liddy Dole in 2000, or, I don’t know, Barry Goldwater Jr. sometime in the 1980s.

It’s easy to say looking back that obviously it was Romney, and not the Huck (or Sarah Palin or Dan Quayle or whoever) who was next in line in 2012, but it wasn’t all that obvious in 2009.

So when someone tells you that Rick Santorum, or Paul Ryan, or even Rand Paul is a lock for the nomination because it always goes to the next in line, feel safe to dismiss it.

What can we say about nomination politics this early? Resources are important. Money, name recognition, endorsements, popularity, dedicated campaign organization: All of those resources are critically important to winning presidential nominations. It’s not entirely clear, unfortunately, which resources are most valuable at this stage, but it’s easy to simply say that more is better, especially more of those things that can multiply over time (so endorsements are great because they can yield money and organization; name recognition has limited utility, although it will help raise money).

So while it’s fun to look at past patterns of where the nominees came from, if you want to know who is winning, look at who has the most resources now.

Shares