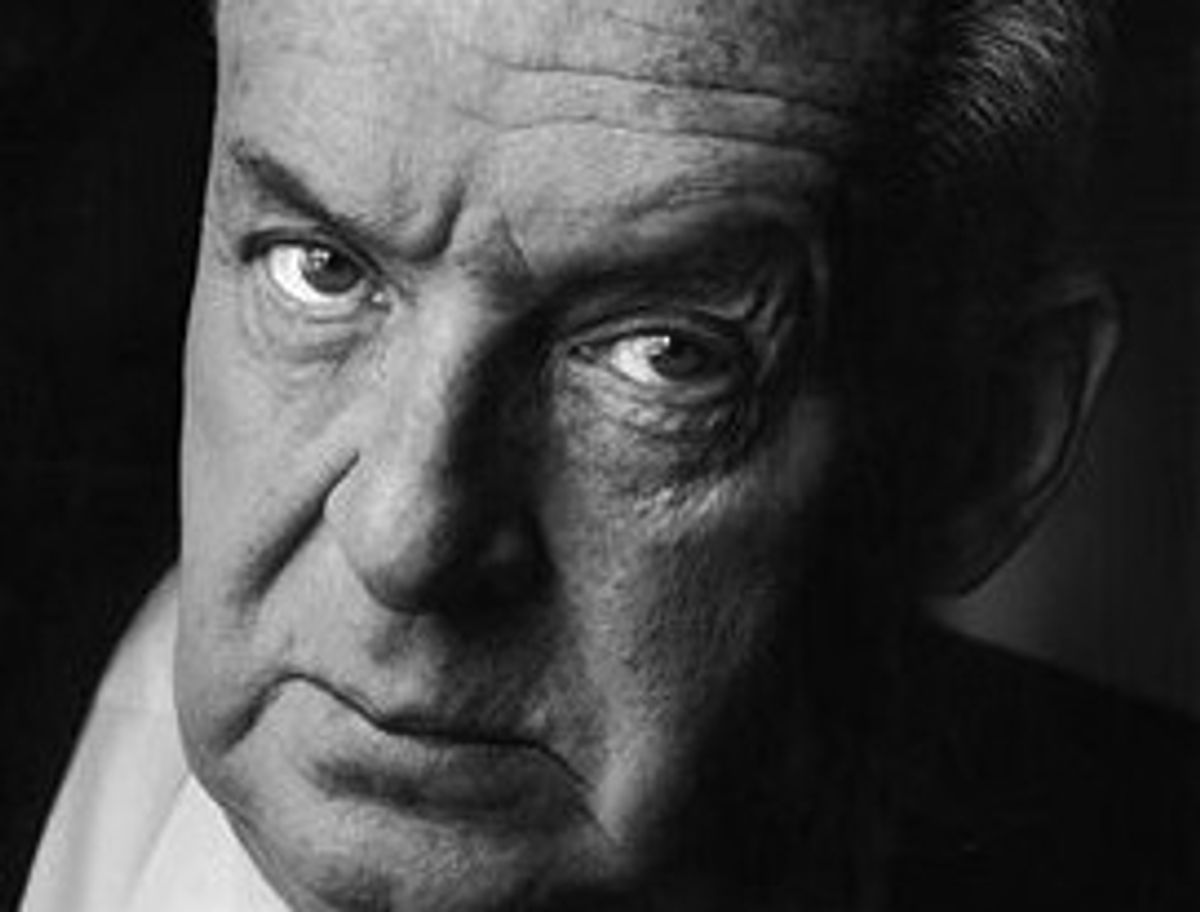

IN THE INTRODUCTION to his novel "Bend Sinister" (1947), Vladimir Nabokov writes the following:

I am not “sincere,” I am not “provocative,” I am not “satirical.” I am neither a didacticist nor an allegorizer. Politics and economics, atomic bombs, primitive and abstract art forms, the entire Orient, symptoms of “thaw” in Soviet Russia, the Future of Mankind, and so on, leave me supremely indifferent.

Nabokov was no stranger to the political atrocities of the 20th century. In 1919, he and his immediate family fled revolutionary Russia on the last ship out of Sevastopol, a vessel aptly named "Nadezhda" (“Hope”). In 1937 he escaped Hitler’s Germany by fleeing to France, and in 1940, just weeks before Paris fell to the Nazis, he boarded a French ocean liner’s last voyage to New York with his Jewish wife and son. So, was his insistence that his art was independent of politics and society fact or fiction? In "The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov," Andrea Pitzer suggests that such pronouncements were merely part of Nabokov’s public façade — “the genteel, charming cosmopolitan, incapable of being dented or diminished by history.” The Nabokov that Pitzer presents to us “is more vulnerable to the past than he publically led the world to believe,” recording events “that have fallen so completely out of public memory that they went unnoticed.” Pitzer is particularly interested in tracing how Nabokov planted references to concentration camps in his art. To prove her point, she chronicles historical events as they unfolded in the course of Nabokov’s life and shows how Nabokov’s works “refract” these events. While the result is an admirable work of archival research, Nabokov’s art, unfortunately, comes out as a mere apparatus for capturing history — a heroic service no doubt but one that raises the question: if all you wanted to do was record events, why go through the trouble of writing fiction? Pitzer suggests that, by burying “his past in his art” and waiting “for readers to exhume it,” Nabokov had devised a new and different method for documenting inhumanity and the history of violence.

If Pitzer is correct, why was Nabokov so cryptic? Pitzer cites Nabokov’s famous assertion that art is difficult and should challenge the reader. But if Nabokov intentionally hid historical information in his fiction as a kind of challenge to his readers, then he was either a sadist for telling them not to look for such content or he was really into reverse psychology. In the introduction to "Bend Sinister," Nabokov dissuades readers from viewing his book as political dystopian fiction: “The story in "Bend Sinister" is not really about life and death in a grotesque police state,” he writes. Yet Pitzer uses quotes from his foreword to argue that the author “directly links” the world of "Bend Sinister" with the totalitarian states in which he lived, those he calls “worlds of tyranny and torture, of Fascists and Bolshevists, of Philistine thinkers and jack-booted baboons.” When put back into context, however, Nabokov’s exact words are: “There can be distinguished, no doubt, certain reflections in the glass directly caused by the idiotic and despicable regimes that we all know and that have brushed against me in the course of my life: worlds of tyranny and torture.” According to Nabokov, to read too much into these reflections is to allow these idiotic and despicable regimes to control the realm of art, the only haven that can declare true independence.

Vladimir Nabokov had a specific term for the kind of reader who obsessively searches for political and social clues in fiction: “the solemn reader.” This “solemn reader” falls into the trap of reading his novel "Bend Sinister," widely recognized as his most political work, for “human interest.” Lecturing about Gogol’s short story “The Overcoat,” Nabokov would remark that the “solemn reader” takes for granted that Gogol’s prime intention was to “denounce the horrors of Russian bureaucracy.” Such reading is not necessarily wrong. It’s just that, according to Nabokov, his and Gogol’s art deals with “something much more than that.” Vera Nabokov once mentioned that “every book by VN is a blow against tyranny, every form of tyranny.” When Nabokov reminds us in "Lectures on Literature" that “the work of art is invariably the creation of a new world … having no obvious connection with the worlds we already know,” he is not advocating that writers employ their stylistic gifts for the sake of showing off. For Nabokov, there exists no greater blow against tyranny than art that refuses to be a vehicle in the service of society.

Now, we might not agree with Nabokov’s ideas about literature and his ways of reading and evaluating literary works. (He was wildly dismissive of a long list of writers deemed great.) In fact, we can read Nabokov however we want, even against the grain of his aesthetic tenets. As Charles Kinbote of "Pale Fire" says: “For better or worse, it is the commentator who has the last word.” More than just commentary, Pitzer’s book is clearly a labor of love, the personal quest of a passionate reader of Nabokov. As she confesses in the introduction, she was “put off by the abuse” that Nabokov “heaped on his characters” and wanted “some sense from Nabokov that he loved what he had created.” So Pitzer went to the archives to find a Nabokov with whom she could be at peace. Pitzer is at her strongest when she shows through meticulous research the potentials of reconstructing the historical world in which Nabokov lived and wrote. It is riveting to read about the odds Nabokov, whom Pitzer aptly calls the “Houdini of history,” was up against when he pulled his “vanishing acts” first out of Russia and then continental Europe. It took a number of sheer coincidences and acts of kindness to lead Nabokov to safety in America. While some of Pitzer’s claims about “forgotten history” might ring as exaggerations, it is fair to argue that today’s readers might not be familiar with all the historical events during Nabokov’s life. When, for example, Nabokov mentions the Solovki labor camp or the Lubyanka dungeon in "Speak, Memory," Pitzer’s account can provide readers with a helpful background. So does this research prove that Nabokov was indeed burying historical clues in his fiction? Yes and no. Instead of merely recording history, Nabokov was deliberately transforming it through the prism of his art. To read his works solemnly and solely for historical clues is to strip away the magic of that art.

Nabokov did not always hide history. He could be direct and poignant, as when describing Pnin’s memories of his first love, Mira Belochkin:

One had to forget — because one could not live with the thought that this graceful, fragile, tender young woman with those eyes, that smile, those gardens and snows in the background, had been brought in a cattle car to an extermination camp and killed by an injection of phenol to the heart, into the gentle heart one had heard beating under one’s lips in the dusk of the past.

History does lurk in the wings of Nabokov’s fiction, but he never gives it center stage. The émigré narrator of Nabokov’s short story "Spring in Fialta," for example, obliquely and scornfully refers to the Russian Revolution as “left-wing theater rumblings backstage.” Interestingly, Pitzer’s own use of theater metaphors to narrate 20th-century history (“other tragedies were waiting in the wings”) suggests one potential way of thinking about the relationship between art and history: Nabokov’s interest in theater.

Outshone by his virtuoso novels, Nabokov’s dramatic works are seldom explored. And yet one of the writer’s first major works is a play that he wrote in Russian when he was only 24 and living in Prague in the winter of 1923 to 1924: "The Tragedy of Mr. Morn." Composed in the wake of the October Revolution, the play was never published or performed in the author’s lifetime. Published posthumously in 1997 in the Russian literary journal "Zvezda," the play is now released for the first time in the United States in an excellent English translation by Thomas Karshan and Anastasia Tolstoy. Already available in the United Kingdom in the summer of 2012, "Morn" has not stirred anywhere close to the frenzy of the 2009 media hurricane of "The Original of Laura." Nevertheless, this play is a gem that deserves our attention. If the unfinished novel "The Original of Laura" revealed to the world the last embers of Nabokov’s genius, "The Tragedy of Mr. Morn" shows the first sparks of brilliance that would evolve in later works such as "Pale Fire" (1962). But "The Tragedy of Mr. Morn" is not only interesting in the ways that it anticipates Nabokov’s mature fiction; "Morn" also shows that instead of just hiding historical material, Nabokov utterly transforms it through the prism of theater.

Set in an imaginary country, the play centers on Morn, a king in disguise whose reign restores prosperity to a land once torn by civil strife. He is in love with Midia, whose husband, a revolutionary named Ganus, has been sent to a labor camp. From this exposition, the play weaves together political intrigue, romantic rivalry, and theatrical self-consciousnessreminiscent of Calderón and Shakespeare. Although Pitzer doesn’t discuss "Morn," all the elements that interest her in Nabokov are already present in this early drama: violence, dictatorships, and mentions of forced labor camps. Indeed, as Thomas Karshan notes in his illuminating introduction, Nabokov would never write so explicitly about revolution and its ideology. Yet already in "Morn," Nabokov is working on how to artistically transfigure historical material to create a new universe of fiction. He finds one source of inspiration in Shakespeare’s history plays, where the political state figures as a kind of theater and where the power of make-believe can topple or rebuild a kingdom as if it were a deck of cards. In "Pale Fire," this theatrical motif will be picked up again when the last king of Zembla escapes through a secret passage connecting his palace to the Royal Theatre.

Nabokov might not have been an accomplished playwright, but he learned and borrowed freely from the art of theater. Among recent academic titles that explore Nabokov’s interest in theater are Siggy Frank’s "Nabokov’s Theatrical Imagination" (2012) and, to a certain extent, Thomas Karshan’s own "Vladimir Nabokov and The Art of Play" (2011). In particular, Siggy Frank not only details the writer’s forays into playwriting, but also traces how theatricality pervades his narrative fiction.

Nabokov’s thoughts on theater also shed light on his attitude toward history. During his first academic engagement in America at Stanford University, the position that helped secure his departure from Europe in 1940, Nabokov taught a summer course on drama. In the lecture titled “The Tragedy of Tragedy,” Nabokov reveals his aversion to the logical determinism that pervades much of playwriting. The tragedy of tragedy that Nabokov has in mind is the genre’s dependence on “conventionally accepted rules of cause and effect” and the oppressive concept of fate, which Nabokov then fights both on aesthetic and moral grounds. Instead of traditional tragedies, Nabokov prefers what he calls the “dream-tragedies” of Shakespeare — "Hamlet" and "King Lear" — as well Henri-René Lenormand’s play "Time Is a Dream." Perhaps from these dramatic feats of imagination Nabokov intuited that treating history more like a dream than a document could be a powerful artistic choice and a blow against tyranny.

While Nabokov might have been the Houdini of history, his art is anything but escapist. In many ways, his lecture on tragedy anticipates Lionel Abel’s seminal 1963 "Metatheatre: A New View of Dramatic Form." Put simply, Abel argues that while classical tragedy presents a world ruled by fate, indifferent gods, and inherent forms, the metaplays of Shakespeare, Calderón, and the modern playwrights that they inspired celebrate not only the artifice of theater, but also the theatricality of life itself. And Abel finds this liberating. If all the world’s a stage and life is a dream, then order is something continually improvised by human striving and imagination. In other words, if the world as we know it has been created by human imagination (at times by the banal and boorish brains of despots) then it is also a world capable of change by other consciousnesses. When Cincinnatus C., the artist of Nabokov’s "Invitation to a Beheading" (1935–1936), bravely goes to his execution and realizes that everything is “coming apart” as though during the striking of a theater set, he not only returns to the bosom of his maker, but also “makes his way in that direction where, to judge by the voices, stood beings akin to him.”

When complimented in an interview for having “a remarkable sense of history and period,” Nabokov responded: “We should define, should we not, what we mean by ‘history.’” The author then expressed his reservations about “history,” which could be “modified by mediocre writers and prejudiced observers.” History as Nabokov knew it held certain ethical traps to which Pitzer’s own historical analysis comes dangerously close. Discussing "Lolita," Pitzer claims that “if Humbert deserves any pity at all, Nabokov leaves one focal point for sympathy: Annabel Leigh, Humbert’s first love, who died of typhus in Corfu in 1923.” According to Pitzer, “thousands of refugees had taken shelter on Corfu in camps.” She also entertains the possibility that Humbert Humbert is Jewish: “As surely as Humbert’s sins are his own, and unforgivable, it is also true that he has been broken by history.” Throughout history, the wounds of history have often been called upon to justify further atrocities and solicit sympathy. While earning him the criticisms of many Russian émigrés, it is perhaps precisely Nabokov’s artistic distance from and skepticism about “history” that prevented him from falling into the trap that Solzhenitsyn did later in his life when he embraced both Putin and ardent nationalism. “I do not believe that ‘history’ exists apart from the historian,” Nabokov said. “If I try to select a keeper of records, I think it safer (for my comfort, at least) to choose my own self.”

Shares