A strange thing happened on Twitter in the middle of March. "Why I Left Google," a year-old post by a former Google executive named James Whittaker, went viral, for the second time.

A fairly scathing denunciation of how Google's corporate culture had changed for the worse, Whittaker's post got a reasonable amount of notice when it was first published. But this time around, the buzz was louder.

Exactly how the screed was born anew is anyone's guess. The precise mechanics of viral transmission are an enduring mystery. Maybe someone was randomly trolling the Web, stumbled across Whittaker's lament, didn't notice the date was March 13, 2012, instead of March 13, 2013, tweeted it, and hit a nerve. Or perhaps one of Google's competitors saw an opening, and struck a clever blow of Twitter meme warfare.

The point is that there was an opening, a raw nerve aching to be hit. That same week, Google had announced that it was killing off Google Reader, probably the most widely used newsreader on the Web, beloved by exactly the kind of power users you might expect to boast legions of Twitter followers. These power users were annoyed and distressed at the imminent disappearance of a service that they depended on. They wanted an explanation. It's possible that many of them, encountering Whittaker's post for the first time, found something substantive to chew on in his argument that Google had sacrificed its innovative "don't be evil" soul in the quest to maximize advertising revenue.

The Google I was passionate about was a technology company that empowered its employees to innovate. The Google I left was an advertising company with a single corporate-mandated focus.

Cue the Google backlash.

Om Malik in GigaOm:

I spent about seven years of my online life on that service. I sent feedback, used it to annotate information and they killed it like a butcher slaughters a chicken. No conversation — dead. The service that drives more traffic than Google+ was sacrificed because it didn’t meet some vague corporate goals; users — many of them life long — be damned.

Thomas Claburn in Information Week.

Trust might be earned and it might be paid for. But whatever trust Google earned in its youth, it has squandered in its adolescence.

* * *

Google is so big, so entrenched in so many aspects of our online lives, and so relentlessly active that in any given week the company makes news on multiple fronts, good and bad. It can be difficult to parse signal from noise amid all the deluge of simultaneous hype and complaints. When I told Google I was writing a story about a possible backlash, I was immediately sent a list of a half-dozen positive stories about the company that had appeared in just the last few weeks.

But in the two weeks after the announcement of Google Reader, a handful of other developments gave Google grouches even more grist to grumble. The same week that Whittaker's post was retweeted around the world for a second time, Google banned the advertising blocking app AdBlock Plus from its Google Play app store. A few days later, SearchEngineLand's Danny Sullivan observed that Google Alerts, a popular service that generates daily email reports on any keywords that you choose to monitor, had been effectively broken for months. And just this week, Twitter erupted with scorn at the news that Google's legal department had objected to a Swedish effort to formalize the definition of the Swedish word for "ungoogleable" (ogooglebar) as "that cannot be found on the Web with a search engine." (Google, in an effort to protect its trademark, wanted the definition to specify that the word meant "cannot be found on the Web with Google and requested the inclusion of a disclaimer noting that "Google" is a registered trademark.)

There may be valid reasons for every single one of these developments. AdBlock Plus undoubtedly interferes with Google's future lifeblood of mobile advertising revenue. Google Alerts, like Google Reader, may not generate enough revenue to merit the kind of engineering resources that keeps it functional. And if I've heard it once in the context of ludicrous trademark infringement cases, I've heard it a million times: If you don't defend your trademarks, you endanger your legal right to keep them. (Though it still seems like a dumb, ham-handed move.)

But whatever the reasons, there's one thing that links them all together. They're just not cool. They betray a my-way-or-the-highway operating stance that is bound to raise hackles. It's no wonder the trade press and power user crowd that once applauded Google for breaking Microsoft's hegemony over the technology realm and for providing an "open" alternative to Apple's closed system is now increasingly suspicious and critical and ready to pounce. When Google debuted a new note-taking service called Google Keep one week ago, nearly every reviewer, from the New York Times on down, was careful to warn that, given the recent example of Google Reader's unceremonious dismissal, there was no guarantee that Google would keep Keep around.

Let's return to Whittaker:

Under [former CEO] Eric Schmidt ads were always in the background. Google was run like an innovation factory, empowering employees to be entrepreneurial through founders' awards, peer bonuses and 20 percent time. Our advertising revenue gave us the headroom to think, innovate and create ...

It turns out that there was one place where the Google innovation machine faltered and that one place mattered a lot: competing with Facebook.... Larry Page himself assumed command to right this wrong. Social became state-owned, a corporate mandate called Google+. It was an ominous name invoking the feeling that Google alone wasn’t enough. Search had to be social. Android had to be social. YouTube, once joyous in their independence, had to be … well, you get the point. Even worse was that innovation had to be social. Ideas that failed to put Google+ at the center of the universe were a distraction.

Suddenly, 20 percent meant half-assed. Google Labs was shut down. App Engine fees were raised. APIs that had been free for years were deprecated or provided for a fee. As the trappings of entrepreneurship were dismantled, derisive talk of the “old Google” and its feeble attempts at competing with Facebook surfaced to justify a “new Google” that promised “more wood behind fewer arrows.”

The days of old Google hiring smart people and empowering them to invent the future was gone. The new Google knew beyond doubt what the future should look like. Employees had gotten it wrong and corporate intervention would set it right again.

Whittaker now works at Microsoft. Reading between the lines, one wonders whether the corporate transition from Schmidt to Page led to some kind of power struggle that didn't work out for Whittaker, pushing him to leave some serious scorched earth behind as he left town. It's also interesting to speculate on whether the ascendance of Page is the explanation for the new, harder-nosed Google.

It's also important not to overreact to the momentary, viral-blog-post-buffeted moods of Twitter. As I was writing this piece, I saw a news release noting that the two most popular app downloads for Apple's mobile devices in 2013 were Google Maps and YouTube. To a certain extent, the people have spoken. As long as they keep speaking in favor of Google's tools, Google will be just fine.

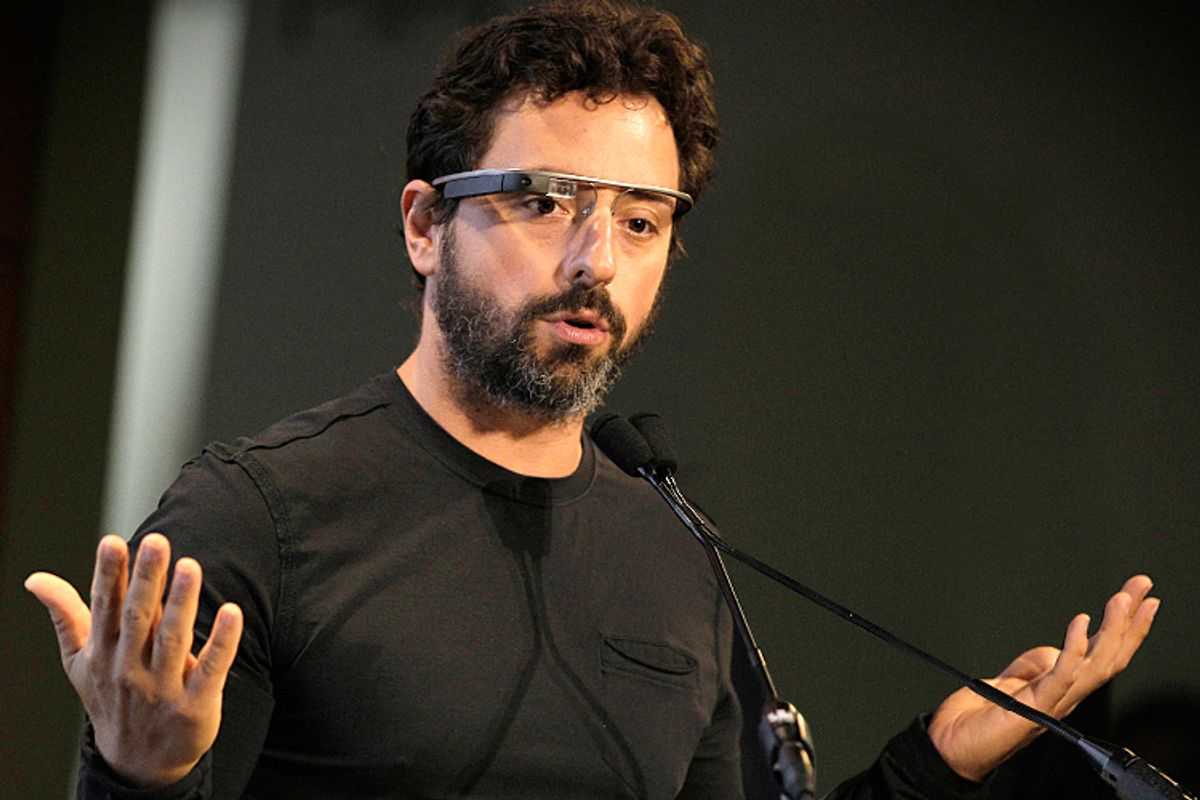

But in a fickle information economy in which giants become dwarves overnight, balancing one's reputation for cool with one's bottom line is trickier than ever. A growing accumulation of incidents that rub users the wrong way creates a climate of dissatisfaction that amplifies our reactions to new abuses. A year ago, maybe we laughed off the "ogooglebar" kerfuffle, ignored Whittaker's post, and dreamed of wearing Google glasses. Now we poke mean fun at overzealous lawyers, see bean-counting corporate realignment behind every new product launch, and savage Google Glass wearers as irredeemable dorks. Perhaps most troublingly, the benefit of the doubt is gone.We're way beyond mocking "don’t be evil." Now our default position toward Google increasingly resembles how we treated Microsoft in the '90s. Google is indispensable, certainly, but not necessarily to be trusted.

In his prescient 2011 book "The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry)," Siva Vaidhyanathan opened his preface by observing that "it's no surprise that we hold the company in deific awe and respect." He then proceeded to spend the entire rest of the book explaining why it was dangerous to allow one company to play such an overwhelmingly dominant role in our informational lives. March 2013 has been the month that Siva's chickens came home to roost. Suddenly "deific awe and respect" seems in short supply. Ungoogleable, almost.

Shares