In the days of 4G wireless networks and Twitter, when virtually every moment of a person’s life can be tracked online and many people offer up that information freely, it’s a rare thing to come across a public figure who not only doesn’t buy into the idea of constant communication but takes themselves in the opposite direction — completely out of the spotlight. The term “recluse” seems like a dirty word, a slur — “private” or “introverted” seem much fairer ways to describe someone than a word that suggests agoraphobia — but that’s how many would describe artists ranging from Emily Dickinson to Marcel Proust, Harper Lee to J.D. Salinger.

Some say that the “recluse” is an endangered species, but to my knowledge, there’s still one artist who is keeping the idea of the private public figure alive: Bill Watterson, writer and illustrator of the beloved comic strip "Calvin and Hobbes."

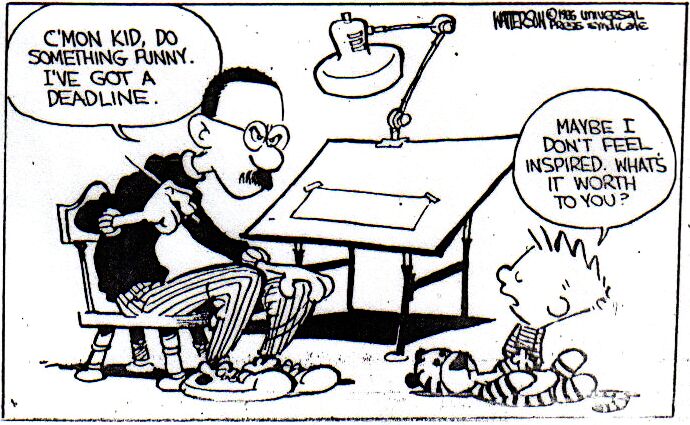

Depicting the adventures of a precocious six year old and his tiger best friend and syndicated by the Universal Press Syndicate in 1985, "Calvin and Hobbes" had a solid decade of unprecedented success, running a total of 3,160 strips long, collected into 18 books, and appearing in nearly 2,500 newspapers across the country. For Watterson, who from the very beginning was averse to the attention "Calvin and Hobbes" brought him, the personal triumph of writing a successful comic strip was at times overshadowed by the burdens that came with it.

“As happy as I was that the strip seemed to be catching on, I was not prepared for the resulting attention,” Watterson wrote in the introduction to "The Complete Calvin and Hobbes," a 2012 compilation of all his work, weighing in at more than 14 pounds. “Cartoonists are a very low grade of celebrity, but any amount of it is weird. Besides disliking the diminished privacy and the inhibiting quality of feeling watched, I valued my anonymous, boring life. In fact, I didn’t see how I could write honestly without it.”

Whereas others have relished such a spotlight, Watterson shrank from the publicity, sure that neither he nor his work would survive what he saw as the curse of celebrity.

“'Calvin and Hobbes' will not exist intact if I do not exist intact,” Watterson told the Los Angeles Times in 1987 when he was 28 years old, new to success, and still unused to the attention it brought him. “And I will not exist intact if I have to put up with all this stuff.”

“This stuff, however,” wrote the reporter, “is the stuff of which cartooning fortunes are made. Sweatshirt sales. Greeting cards. Robin Leach. "Calvin and Hobbes" toys. A profile in People … and pitches from hustlers sniffing fresh meat for a marketplace monopolized by 'Peanuts' and 'Garfield.'”

There were plenty of hustlers — not only businessmen dangling potential millions of dollars of paychecks in front of Watterson and UPS, but the likes of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were even attempting to woo Watterson to give up film rights with trips to Skywalker Ranch — but Watterson wouldn’t budge. The man was nothing if not staunchly dedicated to his personal ethics, and licensing his characters was simply out of the question. “If I’d wanted to sell plush garbage,” Watterson told the Comics Journal in 1989, “I’d have gone to work as a carny.”

“I’m convinced that licensing would sell out the soul of 'Calvin and Hobbes,'” Watterson said in the same article. “The world of a comic strip is much more fragile that most people realize. Once you’ve given up its integrity, that’s it. I want to make sure that never happens.”

After years of fighting, Watterson finally gained full rights to "Calvin and Hobbes" in early 1991, thus ensuring that toy company’s dreams of Spaceman Spiff underpants and stuffed Hobbes dolls on their shelves would never be a reality. But Watterson’s ethical battle still wasn’t over — in fact, it would last well beyond the final "Calvin and Hobbes" panel he drew in December of 1995. This time, it would come in the form of reporters, and the ethics in question were theirs.

Hundreds of fans have undoubtedly made pilgrimages to Chagrin Falls, Watterson’s small hometown to the east of Cleveland, seeking him out even as he made it clear that he wanted to be left alone. And since he more or less disappeared in mid-1990 (his last known public appearance was at his alma mater of Kenyon College in Ohio, where he gave a commencement address titled, “Some Thoughts on the Real World From One Who Glimpsed It and Fled”), dozens of journalists have made the same trip.

The Plain Dealer sent a reporter in 1998 and again in 2003; the Washington Post sent someone in 2003, as did the Cleveland Scene. All the reporters hoped to score that elusive golden interview with the man behind "Calvin and Hobbes," and all found that Watterson proved harder to find than anticipated. The reporters went back to their newspapers more or less empty-handed, little more to show for their trip than a possible sighting from a distance or a brief conversation with Watterson’s mother.

When a private figure becomes so beloved, the line between diligent professional and obsessive fan can quickly become blurred. Author Nevin Martell, for example, talked to Watterson’s friends, colleagues and family for his 2009 book "Looking for Calvin and Hobbes." Years of work resulted in a fairly complete memoir of Martell’s fandom but yielded no interview with Watterson himself, who rebuffed the request for one through his intermediary in many such cases, former UPS editor Lee Salem.

For Joel Schroeder, the director of the documentary "Dear Mr. Watterson” (which will be screened at the Cleveland International Film Festival in April), the decision not to contact Watterson was fairly clear from the days of pre-production. After reading Martell’s book in 2009, the choice became even more obvious — respect Watterson’s privacy. Don’t even try to reach out.

“Our choice not to pursue Watterson for an interview was the right fit for our film,” said Schroeder. “When we went to Chagrin Falls, for example, we did not pursue interviews with his parents; we did not drive past his parent’s house. It was a hands-off approach. And the reason was to try to be clear and communicate that ['Dear Mr. Watterson'] is not about the sensational idea of trying to track him down. It is really about the impact he had through his comic strip.”

In 2010, former Plain Dealer features writer John Campanelli sent email questions to Watterson, not very hopeful that he’d get a response, and struck gold when Watterson wrote back to him with six succinct, yet personable and funny answers, breaking the near-complete radio silence he had skillfully maintained over the preceding two decades.

“Because your work touched so many people, fans feel a connection to you, like they know you,” Campanelli wrote in his email to Watterson. “It really is a sort of rock star/fan relationship. Because of your aversion to attention, how do you deal with that even today?”

“Ah, the life of a newspaper cartoonist,” Watterson answered. “How I miss the groupies, drugs, and trashed hotel rooms! But since my ‘rock star’ days, the public attention has faded a lot. In Pop Culture Time, the 1990s were eons ago. There are occasional flare-ups of weirdness, but mostly I just go about my quiet life and do my best to ignore the rest.”

There comes a time in the dogged search for such a private person that the focus of the quest turns away from the sought and back to the seeker — the goal isn’t to find the person for the sake of listening to what they have to say, so much as finding them to gain the glory that comes along with that. For all the journalists rejected, it’s easy for new ones to imagine that there must be someone able to break through Watterson’s solid exterior; it could be anyone! But Watterson, for one, has said most of what he seems to ever want to say. Pushing any farther, at least when it comes to personal details, is asking for a slap on the wrist — or, worse, anger from an idol.

It would take me less than an hour to get from where I live to Chagrin Falls or Cleveland Heights, where it’s rumored Watterson lives now. I asked people who run in a literary and graphic novel circle if they knew anything about Watterson — novelist and short story writer Dan Chaon, comics writer Derf, and journalist Anne Trubek knew little of his whereabouts and had never met him. I gathered names and contact information of local business owners, jotting down numbers with very little intention of ever actually calling or visiting them. I considered going to Cleveland Heights and sitting in a coffee house, keeping an eye out for a thin man with round glasses vaguely reminiscent of Calvin’s father, just to see what it would feel like. I quickly decided not to. I felt sleazy just thinking about it.

I’d rather stay a fan and admirer than just one of the politely rebuffed masses, yet another rejected journalist with the avid hopes of writing a sensationalist fluff piece. Instead of attempting to track down a man who clearly wants to be left alone, I’ll get back to rereading the 14.3 pounds worth of work that Watterson devoted a decade of life to producing — which is really all you ever need to know about him.

Shares