An ongoing battle between local residents and environmentalists and a Canadian mining company eager to dig for copper in the spectacular Santa Rita Mountains in southern Arizona’s Coronado National Forest has become the poster child for the need to reform a 141-year-old law that governs hard rock mining on federal lands.

A state fish and game department report says the mine would render the northern parts of the Santa Rita Mountains "almost useless.”

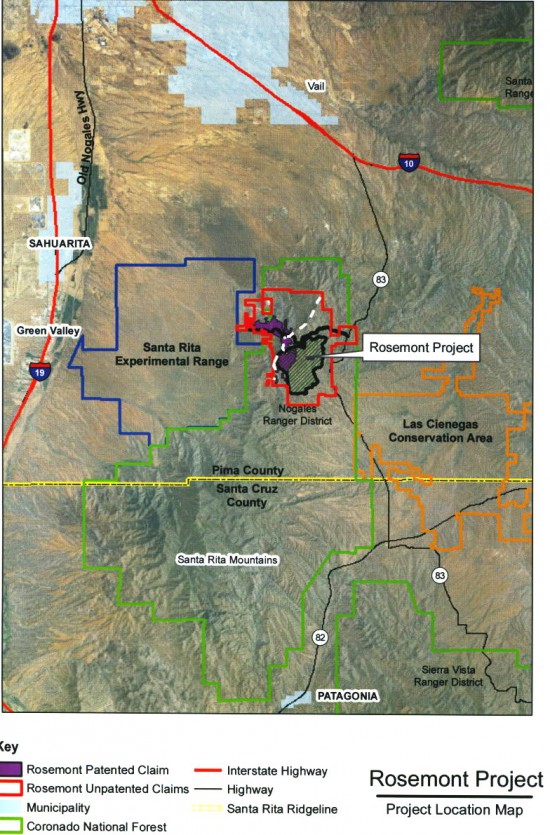

Vancouver-based speculative mining company, Augusta Resource Corporation, and its Arizona subsidiary, Rosemont Copper Company, plan to blast a mile-wide, half-mile deep copper mine on 4,000 acres of the mountains, 50 miles southeast of Tucson. If its proposal goes through, Rosemont claims the mine could supply 5 percent of the country’s copper needs and will bring “thousands of jobs” and “$19 billion in economic stimulus” to southern Arizona.

But opponents of the mine — including the mayor of Tucson, local citizens’ groups, farmers and ranchers, and environmentalists — say these purported economic gains will be negated by the impact of mining activities on the environment and hurt the arid region’s water supply and tourism industry that relies heavily on preserving the mountains’ “sky island” ecosystem. (Tourism and outdoor recreation is Southern Arizona bring in about $2.95 billion a year in revenues, according to a 2007 study by the Sonoran Institute, a land-use advocacy group based in Tucson.)

“This is a high desert grassland area; it is an area where we still have ocelots and jaguars and all kinds of birds and endangered species, it is home to one of the last free running streams in Arizona… it attracts lots of tourists… we could lose all of that,” says Nan Walden, whose family owns a 7,000-acre partly-organic pecan farm to the west of the mountains. The mine, which would draw 5,000 to 6,000 acre-feet of water every year from local aquifers, would affect their farm’s water supply, Walden says.

The project would also bury more than 3,000-acres of mountains, canyons and streams beneath billions of tons of mining waste and pollute the land and water. Mining activity would also disturb more than 60 sacred sites of the Tohono O’odham nation.

Walden and her husband, Dick, were in the San Francisco Bay Area this week to promote "Cyanide Beach" — a short documentary that traces the checkered history of Augusta Resource. According to the film, top officials have been involved in dubious trading practices and were behind a open-pit gold mine in Sardinia, Italy that left behind a trail of unpaid vendors, a misspent government loan, and a botched environmental cleanup. The film raises questions about whether Augusta’s subsidiary, Rosemont Copper, can be trusted to operate the Santa Rita mine without harming the surrounding environment.

Rosemont Copper has poured millions of dollars into expensive public relation campaigns that emphasize that it will “employ water conservation and recycling techniques never before implemented at an Arizona copper mining facility.” These include the use of dry-stack tailings and state-of-the-art processing technologies that, Rosemont says, will result in the mine using 50 percent less water than traditional mining practices. But opponents of the mine remain unconvinced.

They are just pouring in money, making false claims, and fighting a battle of attrition with us,” said Nan Walden, who’s also an environmental lawyer. “It’s exhausting. We can’t keep at it all the time. We do have a business to run.”

The Waldens helped fund the film by investigative journalist John Dougherty, because, they say, there was a dearth of independent media coverage on Rosemont. Rosemont has released its own film in response. (Watch the two films, here and here, back-to-back. They make for an interesting comparative study.)

The Santa Rita Mountains are part of an important wildlife corridor that connects southern Arizona’s sky island mountain ranges — isolated mountains that rise up from surrounding lowlands resulting in cooler, alpine-like “habitat islands” with unique plant and animal species. The area is home to at least 10 endangered and at risk species and includes some precious wetlands that have been designated “Outstanding Arizona Waters” by the state. This means the wetlands qualify for special protection under the US Clean Water Act. In a 2008 report, the Arizona Fish and Game Department said the copper mine’s “effects would be devastating…” and that the “northern parts of the Santa Rita Mountains would be rendered almost useless.”

This region also has a long history of copper mining dating back to the late 1880s, after President Ulysses S. Grant passed the 1872 General Mining Law to promote the development of publicly-owned lands in the then sparsely populated American West. But the mining boom died in the 1950s when the price of copper dropped and the more accessible seams in the region were tapped. Recent growth in demand for the metal — a key component of electronics and renewable energy technologies — has revived mining companies’ interest in the region that still has sizeable copper reserves.

The problem is the old mining law allows companies to buy mineral-bearing public lands for no more than $5 per acre — nineteenth century prices— and to extract hard-rock minerals like gold, silver, and uranium from public lands without making royalty payments to the taxpayer (unlike other industries that extract coal, oil or natural gas). Under the law, anyone with a hard-rock mining claim has “the right to mine” that trumps all other potential uses of public land. Over the years, in challenges to mining permits, the courts have repeatedly said that mining is the “highest and best use of the land,” even if the project being challenged were environmentally unsound.

Based on this law, Rosemont Copper — which bought the Santa Rita mining lease from a real estate developer in 2005 — has already received seven permits required to begin construction. The company is now waiting for the last key Clean Water Act permit from the Army Corps of Engineers.

But the project still faces major hurdles. First, even if the mine gets the Army Corps permit, the US Environmental Protection Agency could veto the corps decision. And the EPA has already raised objections to the protect, saying that it “would eliminate and/or significantly degrade hundreds of acres of aquatic and riparian resources,” including federal waters and critical springs and wetlands.

The company’s environmental impact statement, too, hasn’t yet been approved. Rosemont also faces several legal challenges to the permits it has already received from citizen and environmental groups.

“There is tremendous local opposition to the project, even most of our local elected officials are against it,” Gyale Hartmann, president of Save the Scenic Santa Ritas, a local nonprofit fighting the project, told me over the phone from Tucson. “We feel particularly strongly about this mine because of where it’s located,” she said. “There are other operational copper mines in this area that are not operating at full capacity. If we need more copper why not step up operations there?”

Her group, which successfully fought of a previous American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) proposal to mine the same spot in the 1990s, has filed two lawsuits against the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality challenging the water use and air quality permits granted to the company. “ [Rosemont Copper] came here thinking that we were a bunch of yokels who wouldn’t put up a fight, they didn’t know what they were getting into,” Hartmann said.

Hartmann is confident the project won’t pass despite the company’s claims that it is just one permit away from breaking ground. There were too many holes in the proposal and in the company’s claims about economic benefits, she said. “They keep saying that the mine will reduce America’s dependence on imported copper, but in fact they’ve already promised to sell half of it to companies in Asia and England,” she said.

Hartmann's group also disputes the company’s claims that the mine will create up to 2,900 jobs. It says Augusta Resource’s regulatory filings state that Rosemont’s employment will average 448 workers over the life of the mine.

Rosemont’s parent company isn’t doing very well financially, either. A recent Ernst and Young audit report of the company said there was “substantial doubt” about the company’s ability to continue. It reports that Augusta Resource suffered $9.72 million in losses in 2012 and would probably need to spend more money on the Rosemont mine in 2013 than it has in working capital.

Rosemont Copper has not responded to repeated calls and emails for comment.

Those fighting Rosemont might be confident of a victory, but the fact that the company’s proposal to mine in a critical wildlife habitat has made it so far serves to highlight environmentalists’ concerns about the General Mining Law.

“The Rosemont mine proposal should have never made it this far; it is yet another example of the urgent need to reform the 1872 Mining Law,” says Jennifer Krill, executive director of Earthworks, a mining watchdog group that is working to make changes to the law. “The area is ecologically significant, and includes the only jaguar habitat in the US, and it is critical to Tucson's economy and water supply. Under the 1872 Mining Law, the Forest Service is not allowed to consider these other uses; if it were, then the Rosemont proposal would not even be on the table."

Shares