Just when it seemed that the democratic process had reached its apotheosis with the election of America’s first black president, a political earthquake occurred in 2010 that threatened all that had been accomplished since 1965. Two years after Obama’s election, the midterm elections saw a conservative backlash that swept Republicans back into office in droves. As the media focused on the Republican takeover of the House of Representatives and increases in the Senate, more important developments were occurring closer to home. Republicans now controlled both legislative bodies in 26 states, and 23 won the trifecta, controlling the governorships as well as both statehouses. What happened next was so swift that it caught most observers off guard — and began surreptitiously to reverse the last half-century of voting rights reforms.

All across the country following the 2010 midterms, Republican legislatures passed and governors enacted a series of laws designed to make voting more difficult for Obama’s constituency — minorities, especially the growing Hispanic community; the poor; students; and the elderly or handicapped. These included the creation of voter photo-ID laws, measures affecting registration and early voting, and, in Iowa and Florida, laws to prevent ex-felons from exercising their franchise. (Florida’s governor, in secret, reversed the policies of his Republican predecessors Jeb Bush and Charlie Crist, policies that would have permitted one hundred thousand former felons, predominantly black and Hispanic, to vote in 2012.) Democrats were stunned. “There has never been in my lifetime, since we got rid of the poll tax and all the Jim Crow burdens in voting, the determined effort to limit the franchise that we see today,” said President Bill Clinton in July 2011. Once again, the voting rights of American minorities were in peril.

The newly elected Republican officials were able to act so quickly because they had the help of an ultraconservative organization known as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). Its founder was the late Paul Weyrich, a legendary conservative writer and proselytizer who founded both ALEC and the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank dedicated to limited government, an economy free of federal regulations and the sanctity of traditional marriage. Backed by conservative corporations such as Coca-Cola, Philip Morris, AT&T, Exxon Mobil and Walmart, among many others, and funded by right-wing billionaires Richard Mellon Scaife, the Coors family and David and Charles Koch, ALEC provided services for like-minded legislators and lobbyists. ALEC wrote bills and created the campaigns to pass them. Its spokesmen boasted that “each year, more than 1,000 bills based on its models are introduced in state legislatures, and that approximately 17 percent of those bills become law.”

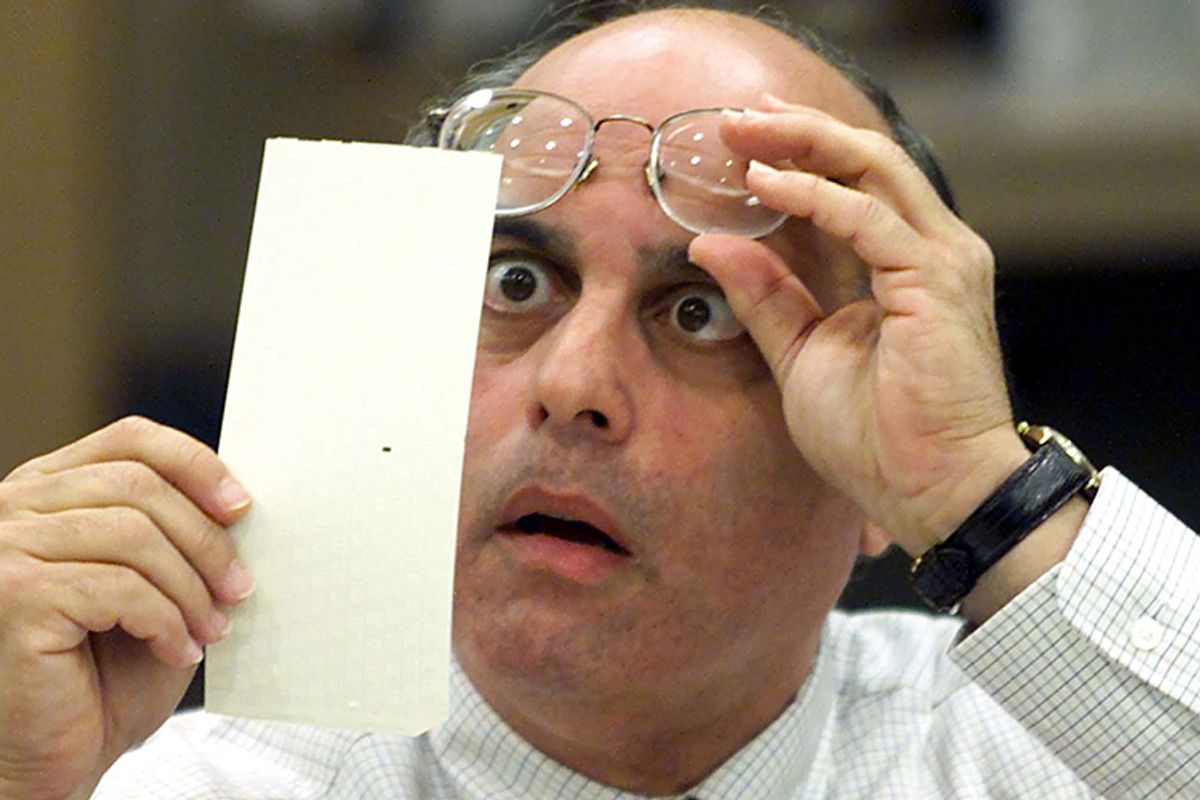

High on ALEC’s agenda were voter identification laws, which it hoped would have the effect of undercutting Obama’s support base so that conservative politicians who supported ALEC’s goals could be elected. Speaking to a convention of evangelicals in 1980, Paul Weyrich said, “Many of our Christians ... want everybody to vote. I don’t want everybody to vote ... As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.” Weyrich believed that America was suffering from what he called “a plague of unlawful voting” that the new laws would combat.

But according to the best analyses, there was almost no evidence of illegal voting. Wisconsin’s attorney general, a Republican, examined the 2008 election returns and discovered that out of 3 million votes cast, just 20 were found to be illegal. A wider study conducted by the Bush Justice Department had found similar results for the period 2002 to 2007. More than 300 million people had voted, and only 86 were found guilty of voter fraud, and most of them were simply mistaken about their eligibility.

Nevertheless, the Bush administration and Republicans, believing in the existence of widespread voter fraud, generally made its elimination a top priority. In 2007, the Bush Justice Department fired seven U.S. attorneys for supposedly failing to prosecute cases of voter fraud that the attorneys claimed did not exist. To combat voter fraud, ALEC proposed a state voter ID for those citizens who lacked a driver’s license or other means of identification that had once been acceptable, like a Social Security card. Among the many young politicians ALEC nurtured was Scott Walker, a future governor of Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s voter photo-ID law was one of the first pieces of legislation the new governor signed into law in 2011, and it became a model many other states followed. It required that potential voters show a current or expired driver’s license, some form of military identification, a U.S. passport, a signed and dated student ID from an accredited state college or university, or a recent certificate of nationalization. If voters had none of these documents, they could present a birth certificate to receive a special photo ID issued by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Such requirements made voting extremely arduous for the very people who disproportionately supported Barack Obama in 2008, such as racial minorities, students and the elderly.

Among those who found it difficult to comply with the new law was Gladys Butterfield, who had voted in every local, state and presidential election since 1932. She had stopped driving decades ago, so she had no license. Her birth certificate was also missing. She did have a baptismal record, but that document was not acceptable as proof of identity in her home state. Therefore, under Wisconsin’s new law, she had to obtain a special government ID available only at an office of the Department of Transportation (DOT) before she could vote in the next presidential election. She was wheelchair-bound, and so she was dependent on a family member to drive her to the nearest DOT office. (She could not apply online because she lacked a current license.) A quarter of the offices were open only one day a month and closed on weekends. Sauk City’s office was perhaps the hardest to visit; in 2012 it was open only four days that entire year. Many other states’ DOT offices posed similar problems: odd schedules, distance from public transportation and the like.

With her daughter Gail’s help, Butterfield applied for a state-certified birth certificate, costing twenty dollars, which she could show as proof of American citizenship. Next she had to visit the DOT. Transporting a wheelchair was a problem, as was the inevitable wait in line to fill out the forms and have her picture taken. She was charged $28 because she did not know that it would not have cost her a cent if she had explicitly requested a free voter ID. DOT officials were instructed not to offer applicants a free ID unless applicants requested one. (When an outraged government employee e-mailed friends of the news and encouraged them to “TELL ANYONE YOU KNOW!! ANYONE!! EVEN IF THEY DON’T NEED THE FREE ID, THEY MAY KNOW SOMEONE THAT DOES!!,” he was abruptly fired for “inappropriately using work email,” said an official.)

Before the Republican victory in the 2010 midterms, only two states had rigorous voter ID requirements. By August 2012, 34 state legislatures had considered photo ID laws and 13 had passed them; five more made it past state legislatures only to be vetoed by the Democratic governors of Montana, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina and New Hampshire. By that same summer, a number of states already had the new laws in place: Pennsylvania (where it was estimated that 9.2 percent of registered voters had no photo ID), Alabama, Mississippi (approved by referendum), Rhode Island, New Hampshire (whose state General Court overrode the governor’s veto) and five whose sponsors were all ALEC members — Kansas, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Wisconsin. In Alabama, Kansas and Tennessee, people wishing to register or vote must show their birth certificate. To acquire that document, they must pay a fee, which many believe is the equivalent of the poll tax, banned by the Constitution’s twenty-fourth amendment. Minnesota’s citizens would vote on a state constitutional amendment in the 2012 election; if passed, voters could cast their ballot after showing a government-issued photo ID.

What these policies had in common, beside their connection to ALEC, was their negative impact on minorities. The nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice at New York University’s Law School estimated in October 2011 that the new voter ID laws could affect more than 21 million potential voters, predominately African Americans, Hispanics, students, the elderly and the poor.

Other voting laws passed in the wake of the 2010 midterms were just as injurious as the voter ID laws and threatened not merely minorities but also people likely to vote for Democratic candidates. Florida’s new voter law turned Jill Cicciarelli, a 35-year-old civics teacher, into a criminal. She inadvertently ran afoul of H.B.1355, which tightened the state’s already strict regulations governing the registration of new voters. The 158-page bill became law 24 hours after it passed because Governor Rick Scott considered it essential to combat “an immediate danger to the public health, safety or welfare.” Cicciarelli, who taught government and sponsored the Student Government Association at New Symrna Beach High School, was on maternity leave when the law went into effect in July 2011, so when she returned to school that fall she was unaware that she was about to commit a crime. In her senior government class she discussed the 2012 presidential election and, as she had many times before, organized a campaign to preregister those students who would turn 18 before November. Eventually 50 students applied, and after a few days she sent the forms to the county election office. “I just want them to be participating in our democracy,” she said later. “The more participation we have, the stronger our democracy will be.”

The new law required third-party registration organizations to register with the state election office, receive an identification number, undergo training and turn in their application forms no later than 48 hours after their completion. (Previously, registration was voluntary and the completion deadline was 10 days, but it was rarely enforced.) Cicciarelli violated each of the new provisions and could be fined up to $1,000 for missing the due date and an additional $1,000 for failing to register. When Ann McFall, Volusia County Supervisor of Elections, learned of Cicciarelli’s infractions in late October, she reluctantly alerted the secretary of state’s office that the teacher had violated the new law’s requirements, potentially a third-degree felony if investigators determined that she was guilty of “willful noncompliance.” “I was sick to my stomach when I did it,” McFall later told a reporter, “but my job was on the line if I ignored it.”

Republican state representative Dorothy Hulkill, running for reelection in 2012, was one person who liked the Florida law. She believed it would limit voter fraud and stop people from “engaging in shady activities designed to give Democrats an unfair advantage.” Who these people were, she did not say.

The controversy over Florida’s new voting law did not stop there, however. Soon five other teachers were accused of similar infractions. The entire group was dubbed the “Subversive Six” by an Internet blogger who had tired of criticizing the Florida schools’ traditional preoccupations, evolution and sex education.

By targeting a wide swath of American voters not because of race but rather because of their political sympathies, the legislators in these states had struck a serious blow to the suffrage of hundreds of thousands of citizens, all in ways that the creators of the Voting Rights Act had never imagined. Because of Florida’s new law, the state chapter of the League of Women Voters announced that for the first time in 72 years, it would not register new voters in 2012. That time-honored job had become too risky. “It would ... require our volunteers to have an attorney on one side and administrative assistant on the other,” said League chapter president Diedre Macnab. She called the law “a war on voters.” Other organizations like Rock the Vote, which registered 2.5 million new voters in 2008, and the Florida Public Interest Research Education Fund also ended their activities. It was not only the young who responded to such registration drives and who now found a well-traveled route to the polls blocked: Census figures indicated that in 2004, 10 million new voters, among them many African Americans and Hispanics, registered with the help of community-based groups. Under the new voting laws, many of these men and women would likely never make it to a voting booth.

Some of these new efforts to restrict voters’ access to the polls exposed significant racial biases on the part of the Republicans responsible for them. Colorado, Iowa and Florida compiled lists of registered voters they thought ineligible and attempted to remove them from the voting rolls. Florida officials determined that 180,000 citizens were suspect; 74 percent of them were African American and Hispanic, groups more likely to be Democrats than Republicans. Governor Rick Scott became so concerned that illegal aliens could vote that he demanded access to the Department of Homeland Security’s database, and they eventually granted his request. The Florida secretary of state found that thousands of registered voters could be considered “potential noncitizens” and removed them from the voting rolls. Further examination by more objective analysts concluded that significant errors had occurred: only 207 of the suspect 180,000 voters were judged unqualified.

Among those caught in the net were elderly World War II veterans and many other longtime American citizens whose only offenses, in many instances, were being nonwhite. Florida’s election supervisors refused to follow the governor’s orders and stopped purging voters from the rolls. Nevertheless, Republican-dominated Lee and Collier Counties continued to remove those they considered suspicious.

Florida’s attempt at voter purging was not a new phenomenon. A more informal practice known as “caging” had been used mostly by Republican campaign officials for decades throughout America. It was simple: Letters marked nonforwardable were sent to black citizens and those that came back unopened resulted in the addressee being removed from the voting lists. No less than the Republican National Committee was found guilty of caging in the 1980s, and a federal decree ordered them to desist at once, although Republicans still employed it decades later.

Some states also attempted to suppress minority voting by curtailing early voting, which had avoided problems such as crowded polling places and voting machinery that often broke down from overuse. Early voting meant that more people could be accommodated over a longer period of time in, for example, Cleveland, Akron, Columbus and Toledo, cities in Ohio with a heavy concentration of pro-Democratic black voters and a scarcity of voting machines. In the two years following the 2010 midterms, Georgia, Maine, Tennessee, West Virginia, Ohio, Florida and Wisconsin all passed laws shortening the period during which citizens could cast their ballots. Ohio and Florida also eliminated voting on the Sunday before the election. This especially could have a profound impact on future minority voting. In 2008, 54 percent of African Americans voted early, many on that Sunday, when churches held “Get Your Souls to the Polls” campaigns that brought blacks and Hispanics to the voting booths. Obama won Florida with 51 percent of the vote in 2008. In Ohio, another narrow victory for Obama, 30 percent of the state’s total voters, 1.4 million people, voted during the early period, which was then 35 days before the election. Under each state’s new law passed in 2011, it was shortened to 16 days.

Voters in Maine were so incensed that the new law had eliminated election-day registration that a coalition of progressive organizations quickly collected 70,000 signatures, enough to trigger the state’s “People’s Veto,” putting the measure to a vote. On November 8, 2011, the law was repealed in a special election: “Maine voters sent a clear message: No one will be denied a right to vote,” noted Shenna Bellows, head of the state’s ACLU.

Although Republicans continued to insist that the new laws were created solely to fight voter fraud, GOP officials twice revealed another motive. At a meeting of the Pennsylvania Republican State Committee in June 2012, Mike Turzai, the House majority leader, boasted openly that Pennsylvania’s new law would affect the next presidential election. Proudly listing the GOP’s achievements, Turzai said, “Voter ID, which is gonna allow Governor Romney to win the state of Pennsylvania: Done.” Similarly, when, in August 2012, the Columbia Dispatch asked Doug Preise, a prominent Republican official and adviser to the state’s governor, why he so strongly supported curtailing early voting in Ohio, Preise admitted, “I really actually feel that we shouldn’t contort the voting process to accommodate the urban — read African American — voter turn-out machine.” These admissions indicate that winning the presidency by suppressing the minority vote was the real reason behind the laws requiring voter IDs, limited voting hours, obstructed registration, and the like that Republican legislatures passed since the party’s victory in 2010.

Excerpted with permission from "Bending Toward Justice: The Voting Rights Act and the Transformation of American Democracy" by Gary May. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2013.

Shares