Allow me to quickly try to tie together some current events (zipping up to NYC to give this talk).

First, you’ve got the Reinhart/Rogoff (R&R) dustup which is generating lots of ink in the AMs papers—more on that in a moment. Second, indicators once again show that the ongoing expansion in American economy continues to underperform, with weak readings on jobs, retail sales, and inflation.

The connective tissue here is contractionary fiscal policy. And while no one or two individuals gets the blame for that, R&R’s work, with its arbitrary threshold (remember, they’re the ones purveying the debt/GDP-above-90%-slows-growth thesis), non-contextualized broad averages across countries, and data errors, is a good example of how economists have misled the debate.

It’s of course worse in Europe, and interestingly, today’s papers also find the IMF backing off austerity prescription a bit, based, btw, on their own empirical findings which show the countries that did the most deficit reduction had the worst growth outcomes and visa versa. But here in the US, fiscal tightening—remember the sequester—is estimated to shave about 1.5% off of our growth this year, concentrated in the second and third quarters.

It will take a lot more than a quick blog post to analyze the deeply damaging fail of economic policy makers both before and following the Great Recession. The more I learn about the R&R paper, the more I’m reminded that deference to top dogs is a big part of the problem. Many people recognized, though without the depth of Herndon et al’s new paper, that this was a bogus and arbitrary finding, averaging together (carelessly, it turns out) decades of economic apples and oranges and proclaiming their 90% rule (yes, they hedged it in some of their writings, but they didn’t in others) with virtually no accounting for key national differences, reverse causality (slow growth leading to high debt), and most importantly, the economic context for the high debt levels. Yet too few top academic economists called them on it (Krugman and Shiller were exceptions).

It’s this last part about context that’s most important, and most missing from the current debate. Consider, for example, this quote from conservative economist Doug Holtz-Eakin in the R&R write-up from today’s NYT, explaining why, despite the new findings re R&R’s mistakes, he still believes them.

The sun still rises in the east. It sets in the west. And a lot of debt is still bad.

In fairness, Doug’s being glib (and nicely Haiku-like) and the newspapers don’t often let you elaborate (he also cites other papers with similar findings). But his quote gets at the problem with R&R and much of the other austerity work: it lacks context. When interest rates are low and output gaps are large, temporarily large deficits are necessary to absorb excess savings and put excess resources back to work. To miss this fundamental insight is to forget critical and painful lessons learned generations ago.

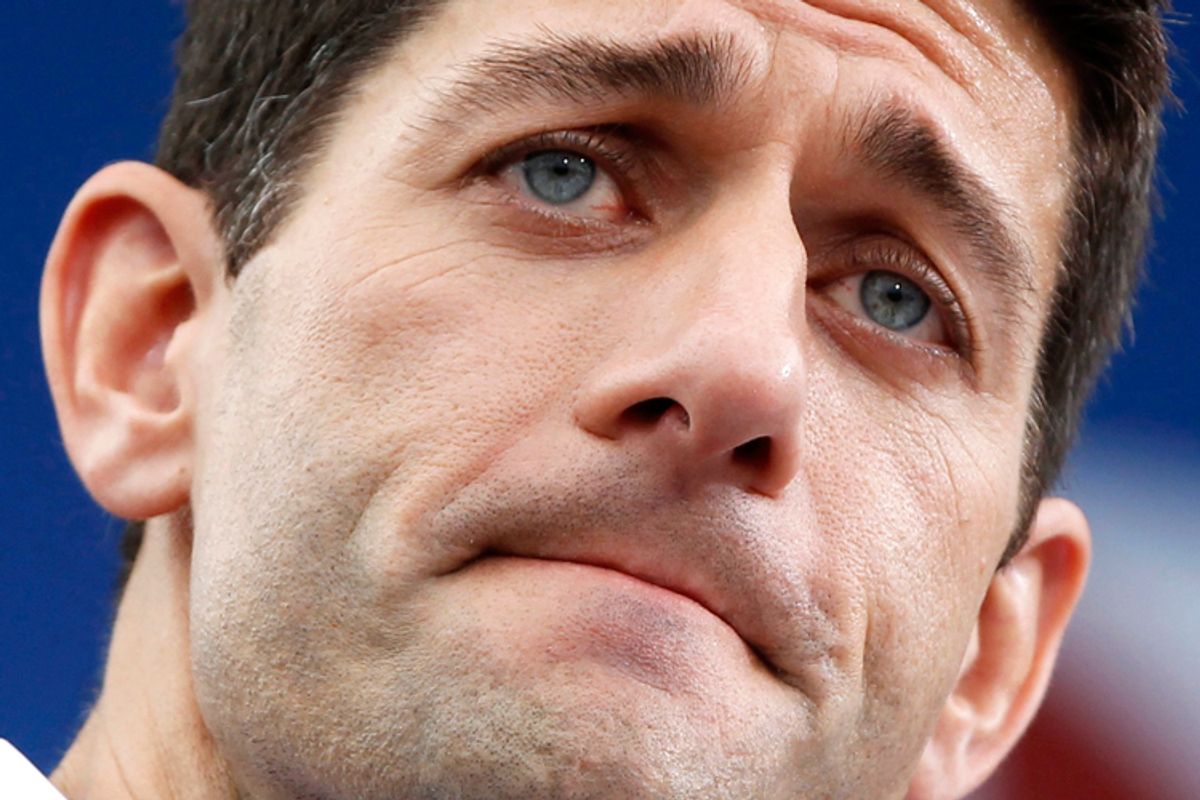

And there’s a political economy dimension to this as well. It’s not a coincidence that Rep Paul Ryan cited the R&R 90% threshold finding in the deeply austere House budget that just passed that body a few weeks ago. Those whose goal is severely shrinking the size of government in general and social insurance in particular need hair-on-fire results like this from established experts to keep the fire going, even in the face of statistics that lean strongly the other way, like the fact that the deficit/GDP is now less than half of what it was in 2010 (like I said, it’s all context, folks—the deficit soared in the recession and is coming down even in our weakened recovery).

As I worried yesterday, it’s likely that the confluence of these dynamics leads to little fallout from the exposure of the shortcomings of R&R’s work along with the IMF’s more recent insights about the real-world impact of austerity in action. Though many of us do what we can to chip away at the false edifice of evidence in support of current fiscal policy, it remains a huge and powerful structure.

Shares