The absolute least Americans can hope for from a major government settlement with a large industry over well-documented crimes is that the industry wouldn’t, after signing the settlement, just continue to commit the same crimes day after day. After all, following the tobacco industry settlement, cigarette makers did manage to stop advertising to teenagers that their product had no medical side effects.

But new evidence reveals the nation’s largest banks have apparently continued to fabricate documents, rip off customers and illegally kick people out of their homes, even after inking a series of settlements over the same abuses. And the worst part of it all is that the main settlement over foreclosure fraud was so weakly written that it actually allows such criminal conduct to occur, at least up to a certain threshold. Potentially hundreds of thousands of homes could be effectively stolen by the big banks without any sanctions.

Before I get into the reasons why, let me step back. It is a sad fact of modern life and the foreclosure mess that I have to differentiate between the litany of settlements granted by the government to the big banks. In this instance, I’m talking about the National Mortgage Settlement, the $25 billion deal concluded a year ago between 49 state attorneys general, federal agencies like the Justice Department and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the five largest mortgage servicers: Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citi and GMAC/Ally Bank. Under the settlement, banks pay a trifling amount in hard dollars to the states as well as foreclosure victims, and provide principal reductions and other loan modifications to struggling borrowers. They also agreed to comply with a broad set of servicing standards for the time period of the settlement, covering three years.

Most of the focus has been on the principal reductions, and whether the banks are actually accomplishing them for the benefit of homeowners. But it’s these servicing standards that are being violated. That’s the inescapable conclusion of new evidence disclosed by the Center for Investigative Reporting and NBC Bay Area. Focusing on mortgage documents and foreclosures in the San Francisco region, they found that “banks and their subsidiaries continue to file invalid documents and foreclose on properties to which they appear to have no legal right.”

In one case, mechanical engineer Joji Thomas, in a last-ditch bid to save his home, delivered a cashier’s check for $27,777.85 to Bank of America, which promptly lost the payment, and foreclosed anyway. In another case, BofA transferred a property to a separate entity that was already closed down, and they clumsily switched the dates on the document to make it look correct. Reporters also uncovered documents prepared by “robo-signers,” individuals hired to attest to the veracity of thousands of mortgage documents without having any underlying knowledge of the contents (basically a mass perjury scheme).

These are precisely the kinds of abuses that state and federal regulators professed to stop with the National Mortgage Settlement. And this is not the only evidence that Bank of America and its counterparts simply went on with business as usual, fabricating documents to prove a shaky chain of ownership before initiating foreclosures, or ripping off borrowers seeking a modification or trying to save their homes. A few brave county recording clerks have examined mortgage documents in their offices and found massive fraud. And the same week that state and local officials announced the settlement, Wells Fargo posted online job listings seeking a “loan servicing specialist” to basically robo-sign documents.

The natural question to ask, then, is whether these criminal activities violate the terms of the National Mortgage Settlement. Could this be the lever to reopen the entire foreclosure fraud case against the banks?

The answer is: yes and no. The individual cases do violate the terms. Banks agreed in the settlement to stop robo-signing, to provide modifications for those homeowners who qualify, to keep accurate payment records and deposit payments properly, to only charge applicable fees, and other steps. There’s even an oversight monitor, empowered to check incoming data from the banks, ensure compliance, and make quarterly reports on their actions.

But there’s a bit of a hitch. As writer and attorney Abigail Field first pointed out last year, for all of these different servicing standards, the banks have a “threshold error rate” that allows them to violate their obligations, up to and including illegally taking someone’s home, a certain amount of times. For the vast majority of standards, the threshold error rate is 5 percent (for a few it’s as high as 10 percent). That means that banks could violate these standards, which often leads to illegal foreclosures, on one out of every 20 mortgages they service, and the settlement monitor has no ability to do anything about it. For context, RealtyTrac estimated 1.8 million foreclosure filings just in 2012. Under the National Mortgage Settlement, 90,000 of those could be fraudulent, without sanction.

I asked Alan White, law professor at City University of New York with expertise on foreclosures, if this was accurate. “Abigail Field’s analysis is essentially correct,” White replied. “The cases described in the [Center for Investigative Reporting/NBC Bay Area] report would violate the terms of the settlement, but would not result in enforcement by the monitor or monitoring committee unless the number of similar cases detected exceeded the thresholds.”

It gets worse. That 5 percent threshold is based on “reportable errors” in a given reporting period, such as a quarter. The settlement monitor, Joseph Smith, does issue quarterly reports, but as it says right in the Office of Mortgage Settlement Oversight FAQ and in the settlement language, the oversight process begins with compliance reports from the banks themselves.

An “Internal Review Group” tests the servicing standards to compute the quarterly metrics. They are allegedly “independent from the line of business whose performance is being measured,” but they are still paid by that bank, and they compose the baseline review that the settlement monitor uses. The monitor can solicit more information from the banks if he perceives a noncompliance problem (though he doesn’t really have the resources to engage in a full review). But really, their job is one of checking the banks’ work. If this is such a good idea, we should stop sending out food inspectors and let agribusiness self-report their findings on tainted meat and produce, and the inspectors will sit back in Washington and verify everything. (Oh wait, we’re doing that too.)

The first court-ordered quarterly report from the settlement monitor is due in May, and there’s little reason to believe it will give anything other than a free pass. Even if by some miracle the monitor did find violations above the threshold, under the settlement, the banks have the right to appeal the findings. The settlement monitor must “confer” with the servicer over noncompliance, and the servicers have the “right to cure” any violation, sort of a “no harm, no foul” situation where the bank fixes some errors to get below the threshold.

“I certainly agree that the error tolerance is a huge concession to the banks,” said law professor Alan White. “I think the banks sold the AGs on the idea that the problems were all in 2009-2010, while going forward the problems were to be fixed. Some tolerance for error seems reasonable, but 5 percent of the mortgages in the U.S. is 2.5 million accounts. The agreement should at least have required all mortgage accounts with errors to be fixed and compensated for.”

White also pointed out that homeowners would still have the ability, in many states, to sue the bank for breaking the law. But if a homeowner had the kind of resources needed to sue a giant bank, they probably wouldn’t have ever been in foreclosure in the first place.

One of the main points of a law enforcement apparatus is to collectively look out for individual abuses, and to use their leverage and resources to bring criminal enterprises to justice. That just isn’t happening in the case of foreclosure fraud. Instead, we see settlements where the criminal conduct gets institutionalized, and where hundreds of thousands of violations go unpunished (really all of the violations -- since there’s no independent, workable compliance system in place).

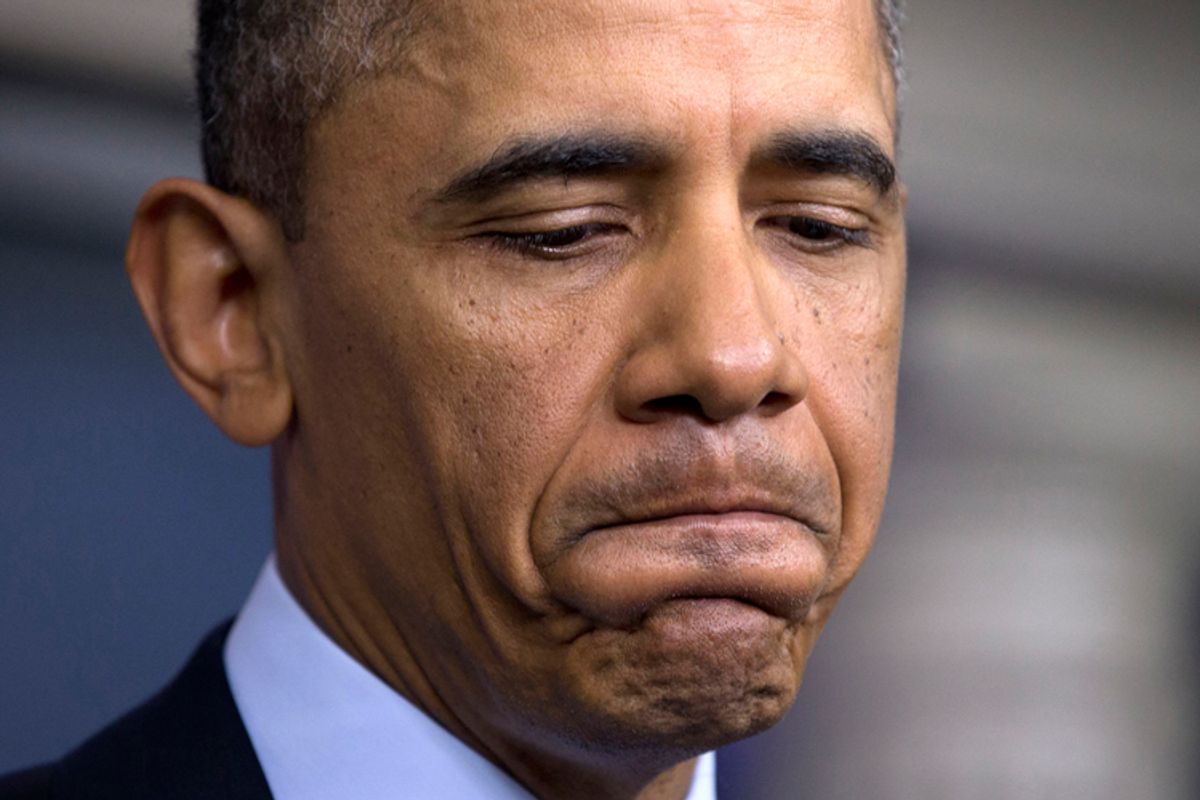

When announcing the National Mortgage Settlement, President Obama said that it would “end some of the most abusive practices of the mortgage industry, and begin to turn the page on an era of recklessness that has left so much damage in its wake.” It does not appear that any of those abusive practices have ended. And the government, at all levels, has basically walked away from its responsibility to protect homeowners.

Shares