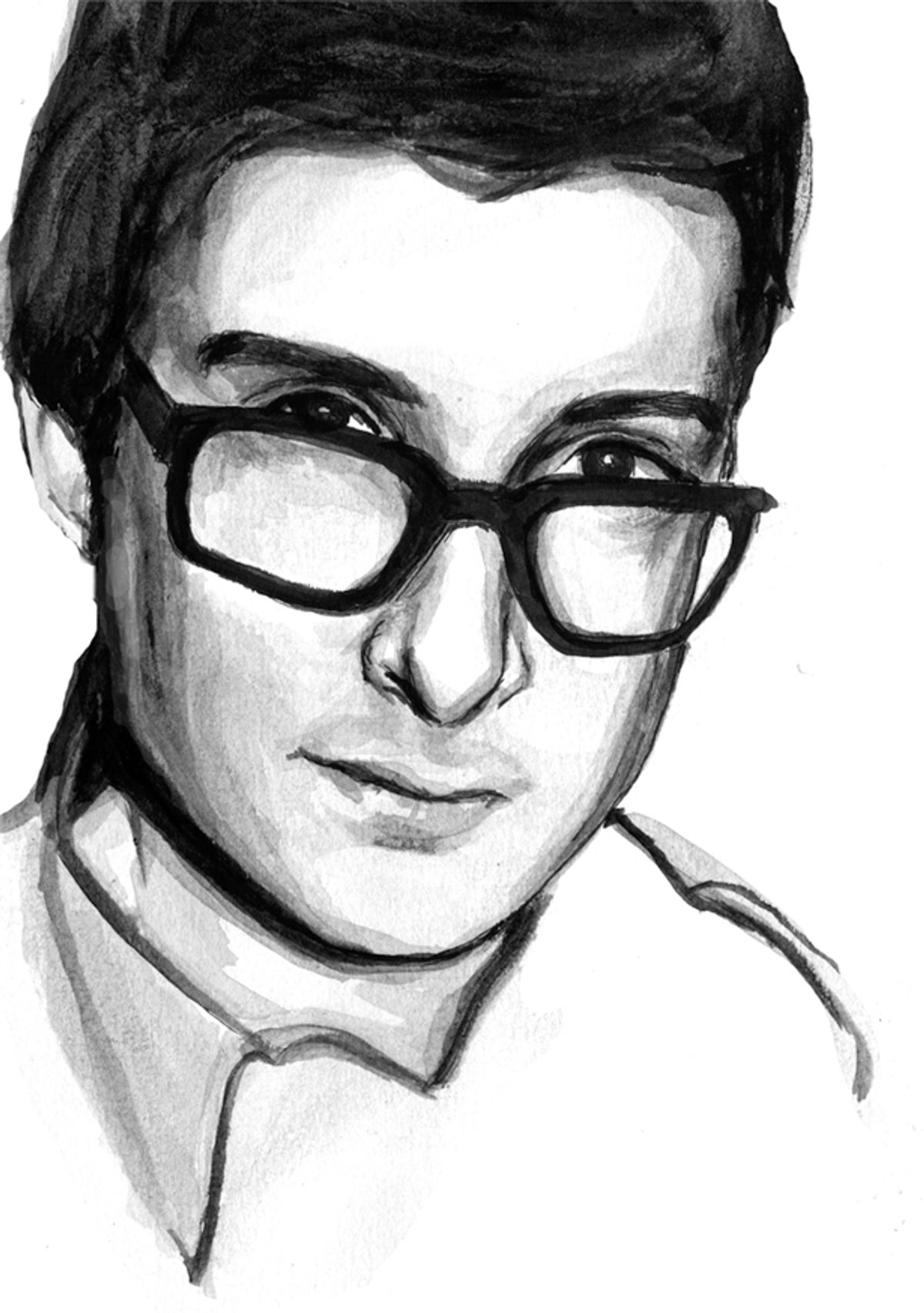

During Occupy's most resonant days in New York in late 2011 and early 2012, regular marches and protests led typically to at least a handful of arrests. Those nights, tired bodies would trickle out of lower Manhattan's central booking, slapped with minor charges, into the arms of supportive friends and activist allies holding vigil outside. Gerald "Jerry" Koch, now 24, was already an old hand at jail support for activists by that time. His suited, skinny frame haunted court buildings until the early hours following arrests, helping gather bail funds and legal support. Under Koch's vigilant, pestering watch, the holding cells filled with political protesters would be emptied as soon as possible.

Now Koch -- my longtime friend, Jerry -- faces up to a year and a half in jail himself. He is the latest anarchist in the U.S. to have been subpoenaed to testify before a federal grand jury. He will not cooperate and his silence could land him months in federal custody, without charge or conviction for a crime. I have written at some length in recent months about the federal grand jury system, which I describe as one of the blackest boxes in the judicial arsenal. I noted, for example, how four anarchists in the Pacific Northwest were jailed for resisting cooperation with a Seattle grand jury, believed to be investigating property damage wrought against the city on May Day 2012.

Three of the Northwest grand jury resisters were held in solitary confinement for much of their five-month detainment. Again, they were not charged with or convicted of any crimes. I noted too how prosecutors in Massachusetts pushed journalist Quinn Norton into becoming a "reluctant witness" in the grand jury investigation into now-deceased technologist Aaron Swartz. Norton, looking back on her experience in light of her friend's suicide, called the process "the mechanics of snitching."

Jerry's case is a particularly strange one. In a move his legal team sees as highly unusual, the former New School student is now facing his second grand jury subpoena investigating the same incident. In 2008, Jerry refused to cooperate with a grand jury launched to investigate the use of an incendiary devise at a Times Square army recruitment center. The so-called bicycle bombing shattered a window but injured no one. Jerry is not under investigation for the incident, but prosecutors claimed in 2008 that he overheard a conversation at a bar in which the suspect was identified. Jerry rejected their claim then, as he does now, having been called to testify again. Now, as then, Jerry will not cooperate on political grounds -- grand juries have for some decades been used as fishing expeditions by the government used to intimidate, deter and undermine radical and dissident communities.

"The government knows Jerry has no information for them in relation to the investigation into the Times Square incident. They also know Jerry won't talk. But they've decided to attempt to coerce him to talk anyway," said David Rankin, one of the attorneys advising Jerry. Rankin told me that -- given Jerry's record of grand jury resistance and his status as a well-known anarchist and legal activist in New York -- "the possibility is certainly left open" that Jerry's case is intended to chill others thinking of grand jury non-cooperation.

Rankin, echoing comments I'd heard earlier this year from National Lawyers Guild director Heidi Boghosian, noted that while grand juries "conjure to mind the idea of gatekeepers for government function, rather than props for prosecutors, they are ripe and susceptible for abuse." As Boghosian told me, "abuse of grand juries includes attempts to gather intelligence or information otherwise not easily obtained by the FBI."

Meanwhile Jerry looks tired and pale (paler even than usual) as he awaits his first grand jury hearing this coming Thursday. At this hearing, and others that may follow, he will refuse to talk and may be taken straight into federal custody. He described himself as "grimly resolute" when we spoke a few days ago. "Any time you're subpoenaed in a matter like this and you refuse to cooperate, you have to be prepared to go to prison. The fact that I did not last time is, I'm told, incredibly atypical."

It seems an obvious abrogation of the spirit, at least, of the writ of habeas corpus, that an individual could be jailed without being charged or convicted of any crime. But the shrouded grand jury system has coercive imprisonment inscribed into the letter of our federal justice system. "It's actually lawful for the prosecution to hold an individual in order to coerce cooperation, but unlawful to hold the person as a form of punishment," NLG's Boghosian told me last year when I first wrote about grand jury resistance for Truthout. As I explained when reporting on the Northwest grand jury resisters:

The closed-door procedures are rare instances in which an individual loses the right to remain silent...The grand jury can grant a subpoenaed individual personal immunity; Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination are therefore protected, but silence is not. In these instances, refusal to speak can be considered civil contempt. Non-cooperators can be jailed for the 18-month length of the grand jury.

Yet if federal prosecutors in New York have hidden intention, as activists fear, of using Jerry to find out about anarchist activity in the city, their fishing will yield nothing. New York's (often disjointed) radical milieu has seen Jerry resist a grand jury once before and knows he will do so again, even if placed in solitary confinement. As such, a strong support network has come together to spread the word about Jerry's case, the coercive functioning of grand juries and resistance. Artist friends designed T-shirts, a call was put out to "pack the court" on Thursday, tech-aware friends were swift to put up a website to share information and raise funds for Jerry's prison commissary and legal costs. For Jerry, it's been a heartening and a resolve-strengthening show of solidarity. "While the feds may rely on a strategy of going after anarchists to uncover their interpersonal and political connections, people see how powerful a united front is and our communities become more resilient, " he said.

A representative from the New York U.S. Attorneys Office told Salon that the office does not offer comment, confirmations or denials regarding grand jury investigations or subpoenas.

Meanwhile, all the resolve in the world can't attenuate the fear of imprisonment -- for Jerry or his loved ones. His long-term partner, Amanda Clarke, whose hair I've seen dyed every hue from palest pink to raven black, carries the burden that her partner could be locked away from her for over a year. "I feel like I've aged 10 years. As the [hearing] date gets closer, it's harder to live life as normal," she told me this week, having poured her every spare hour into Jerry's support network. "When I explained the situation to my mother, who is not political, and other non-political friends, I felt I sounded like a conspiracy theorist -- no one thought you could go to jail without a conviction, for no punitive purpose."

Yet grand juries provide this dark loophole, and Jerry -- like the grand jury resisters in the Northwest, and numerous 1990s animal rights activists before them and black radicals before them -- faces incarceration for his silence. As A.M. Gittlitz, writing for Truthout on Jerry's situation, noted, "the antiquated grand jury model comes pretty close to the puritanical damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don't methods of pre-Constitutional trials." And for my friend Jerry -- described by his partner as "the most resolute man" she knows -- the silver lining is thin but bright. In the context of New York radical politics regularly centered around posturing and blustering, Jerry's resistance is potent. For him, this silence is "the best example of meaning what you say."

Shares