In today’s saturated memoir market, Mary Karr’s still sizzle. The Liars' Club, detailing her tough Texan upbringing—complete with her mother’s gun-waving schizophrenic breakdown and her father’s alcoholic buddies, who gave the book its title—burst onto the scene in 1995. Some say the book spawned a whole bloody genre of ‘90s memoirs featuring addiction as a leading theme, with the likes of Hornbacher, Flynn and Frey following in her wake.

In today’s saturated memoir market, Mary Karr’s still sizzle. The Liars' Club, detailing her tough Texan upbringing—complete with her mother’s gun-waving schizophrenic breakdown and her father’s alcoholic buddies, who gave the book its title—burst onto the scene in 1995. Some say the book spawned a whole bloody genre of ‘90s memoirs featuring addiction as a leading theme, with the likes of Hornbacher, Flynn and Frey following in her wake.

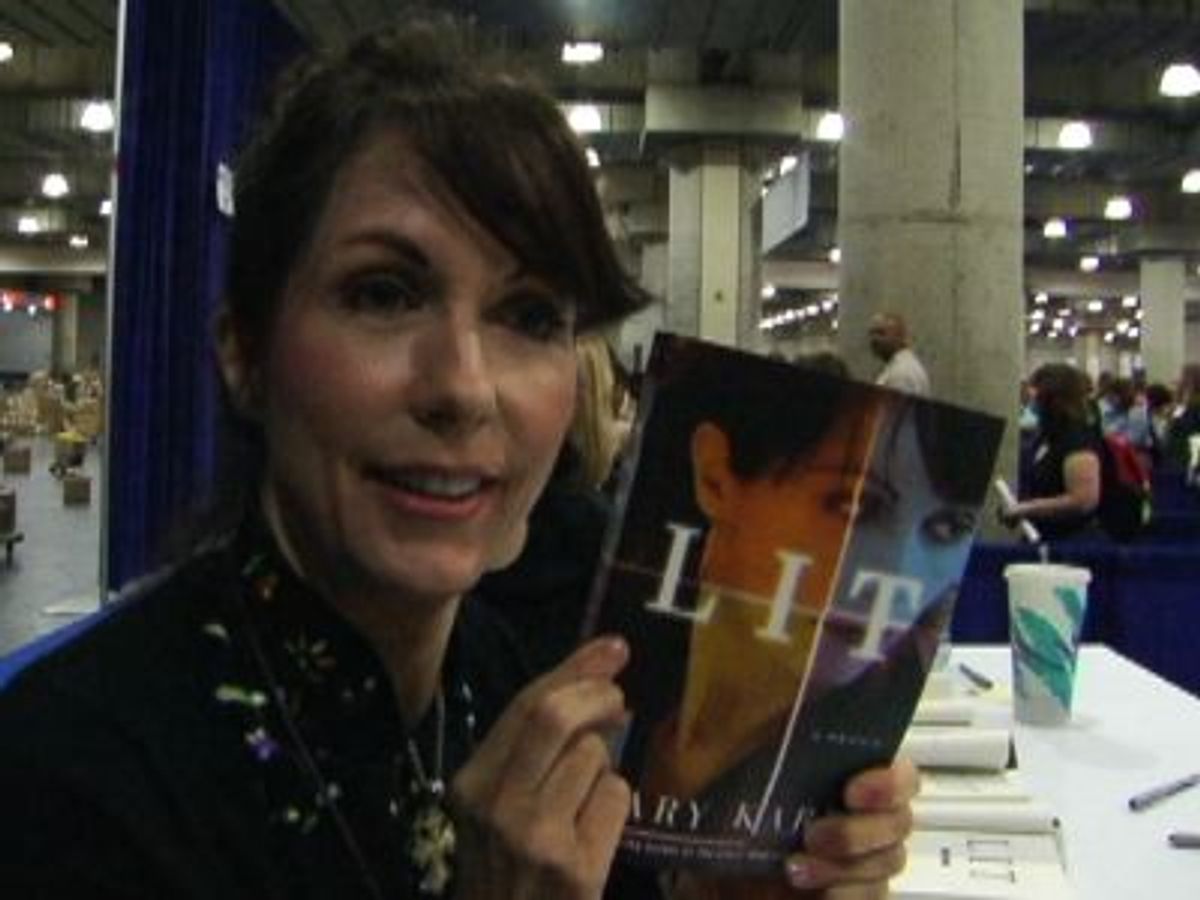

Karr, 58, has been sober for 24 years. She has published four volumes of poetry—most recently Sinners Welcome—as well as two other memoirs: 2000’s Cherry, which dealt with her adolescence, and 2009’s bestseller Lit, which chronicles her recovery from alcoholism. Readers see Karr slowly moving from desolation, trepidation and booze-fueled mania to a mysterious new openness and peace—due partly to an unlikely-seeming conversion to Catholicism. Still, she’s maintained her acerbic wit, outlaw sensibility and lightning-tongued, sailor-mouthed interrogation of anyone in spitting distance.

Karr teaches in the Creative Writing Program at Syracuse University, where I once took a memoir class with her. On the first day she got in a huge spat with the program director, who came in and told her she was in the wrong classroom. They traded some choice barbs and he walked out. Then she broke character and told us to write down everything that happened—it had all been an act. The class argued long and hard about whether he was wearing pants or long shorts, and the exact wording of the final insult. Our recollections of such a recent event, as well as our personal reactions, varied wildly. The exercise demonstrated how inaccurate memoir is. Karr gave The Fix a chance to see if interview can do any better.

The Paris Review called you “surprisingly diffident when it comes to talking about [your]self.” Have meetings and therapy helped you become more comfortable with that?

Everything I wanted people to know I’ve already presented, and in some ways I’m more candid in talking about myself than I was before. When you surrender, you get used to a certain level of candor—you know, the old thing, you’re only as sick as your secrets. You develop a confidence in truth-telling. Part of my drinking was so much about trying not to feel things, to not feel how I actually felt, and the terrible thing about being so hidden is if people tell you they love you…it kinda doesn’t sink in. You always think, if you’re hiding things, How could you know who I am? You don’t know who I am, so how could you love me? Saying who I am, and trying to be as candid as possible as part of practicing the principles, has permitted me to actually connect with people for the first time in my life. It’s ended lifelong exile.

They always say God is in the truth, and I’ve ended loneliness and been able to feel connected by saying who I am and how I feel. I’m sort of comfortable to the degree to which I’m an asshole. It’s not like I’m not an asshole—people know the ways I’m an asshole and it’s within the realm of acceptable asshole-ocity. Part of my drinking and depression was having a voice in my head that was constantly criticizing everybody. I was sort of brought up that way, hypercritical, and I feel like my spiritual practice is a constant correction out of judging everybody else. But I think I’m more critical of myself than anybody, strangely enough, as marvelous as I am.

It’s generally agreed that the enormous success of The Liars' Club spurred a lot more confessional memoirs. But since then, there’s also been a trend in other media to broadcast people’s deepest secrets in a way that’s often seen as exploitive. What do you think about shows like Intervention and so on?

I think the problem with visual media like TV is that they’re reductive. They don’t show the psychological complexity, the real struggle and practice of what it is to have to give up the substance. I think Dr. Drew should be shot. I really do. That guy...small wonder that everybody who’s on 'Celebrity Drug House' or whatever it is would like to blow their fucking brains out. He seems like the most malevolent—I’m sure he and means well, I’m sure he has benevolent impulses—but he seems so insincere and exploitative. And also, being told, “Oh yes, you are special because you’re a celebrity and trying to get sober”… I think those shows, especially with celebrities, are awful, and that’s why anonymity is important: Nobody should be a spokesperson. I’m not an example of anything, and the best way to learn about how to quit drinking is to spend a lot of time talking one-on-one with people who have done it.

James Frey is another famous memoirist and addict—a highly controversial one. Do you want to share your opinion of him, or should I nix that question?

No, no, go ahead. He was the guy who wanted nothing to do with AA—and look how well you turned out, you lying sack of shit! I felt sorry for that guy for a while and then when he started that thing—let’s rip off young people and exploit them—that thing he’s doing is just...really reprehensible, I don’t quite understand it.

If we can talk about your relationship with David Foster Wallace in the early ‘90s—did you get sober together?

He was in rehab and we’d met through friends; he was in rehab down the street and I lived in Belmont, Mass., which is where McLean [Hospital] is. When he got kicked out of Harvard they slam-dunked him in McLean, where I’d eventually do a happy little stint. One of the Whiting fellows said, "Can you contact him?" So I brought him a batch of brownies. I thought it was super sweet that they did that. I was about a month clean; his sobriety date was about a month after mine. So we ran into each other a lot. He was in a halfway house where I did volunteer work. I would drive people to job interviews and stuff like that; there were a lot of disabled people, people who only had one hand or whatever. Everybody there had to have a job and I drove a lot of people around. So I saw him there quite a bit, and we had a lot of mutual friends, many of whom ended up in Infinite Jest in a way I thought was…I really thought was unkind.

I remember you saying how a lot of Infinite Jest was lifted straight from meetings, despite the anonymity tradition. But some would say storytelling is always plagiarism, and maybe his book did people good; where’s the line?

Yeah, I thought it was pretty awful. Another person who does that is Augusten Burroughs. Everybody I ever wrote about, including David, I talked with in advance and said, “This is what I wanna do.” I talked to David before… I wasn’t going to use his name, then after he died, I’d talked to him before he did it and included him enough that I was gonna give him a pseudonym—which he said he didn’t care about, but nonetheless…then he was dead before the book came out. Tragically, stupidly...moron. Moron.

How much do you think his addiction or sobriety had to do with his death [by suicide in 2008]?

David had tried to kill himself three times before that, so you can’t slap that on it. I think being sober kept him alive way longer than he would have made it otherwise. But he wasn’t exactly sober by my measure: He was taking lots of anti-anxiety meds and stuff I consider chemically no different, so I don’t know exactly. I wasn’t in touch with him the last six months of his life. Such a tragic thing. And you know, I don’t know his wife but it seems like such a nasty fucking thing to do. Here’s this woman who’s been trying to take care of you and…I guess I could’ve imagined myself in that situation too easily, and I wouldn’t have been as nice about it as she was. I was lucky I wasn’t, I guess, but damn.

I think we kept each other alive to some extent, for a period of time when we were trying to quit using and it was all but impossible for each of us to do that. And I think our friendship and sobriety was important to both of us. I told him a lot of things about how he was writing. Everybody was very in awe of him because he was so much smarter than everybody. I’d been living in Cambridge where everybody was smarter than everybody, and I’d sort of decided that smart wasn’t that big of a deal. Not that it’s not a great advantage, but in his case I think it was a great disadvantage.

There’s this idea of the tortured artist, or of a link between depression and creativity—is that true and necessary? If so, how do you make meaningful art after recovery, if you’re no longer tortured?

Well, I don’t know, maybe you don’t. I’ve been sober almost 25 years and anything anyone’s ever bought from me has been written when I was sober. If I hadn’t been, I would’ve been like David, swinging from a fucking noose. That really cuts down on your creativity. [Laughs]

When was super depressed, I wasn’t working—I was always too depressed. Hemingway did his best work when he didn’t drink, then he drank himself to death and blew his head off with a shotgun. Someone asked John Cheever, “What’d you learn from Hemingway?” and he said “I learned not to blow my head off with a shotgun.” I remember going to the Michigan poetry festival, meeting Etheridge Knight there and Robert Creeley. Creeley was so drunk—he was reading and he only had one eye, of course, and had to hold his book like two inches from his face using his one good eye. But you look at somebody like George Saunders—I think he’s the best short story writer in English alive—that’s somebody who tries very hard to live a sane, alert life.

You’re present when you’re not drinking a fifth of Jack Daniel’s every day. It’s probably better for your writing career, you know? I think being tortured as a virtue is a kind of antiquated sense of what it is to be an artist. It comes out of that Symbolist idea, back to Rimbaud and all that disordering of the senses and all of that being some exalted state. When I’ve been that way, I’ve always been less exalted than I would have liked.

So in the beginning you said you weren’t going to talk about AA. I was planning to ask whether you still go to meetings or have a sponsor. Should I nix that?

Well, I guess what I would say is, I always talk to people who are trying to stay sober and trying to have some kind of connection or community. And I spend a lot of time talking to young women with little kids who were trying to quit drinking, because when I was a young woman with a little kid and I was trying to quit drinking and a single mom, it was so hard; I was so deranged. So I feel an obligation to be of service. And there were people who helped me and talked to me and talked to my kid, who made places in their lives when I was so isolated—I want to be available to them— to any woman I have time for who is raising a kid and trying to quit drinking, I want to be available to them. So I guess I’d talk to that with that amount of a fig leaf.

I’m going to Michigan this week to talk to women at an organization that runs domestic violence shelters for women who are in violent relationships and struggling with addiction, or their partners are.

Do you think some people have addictive tendencies that both precede and outlast active use: the “addictive personality”? I’m thinking, now, about your habit of coming into class with two giant Wegmans green teas, and the gregarious ferocity with which you approach your students, and any conversation, which kinda scares people sometimes...

Oh, yeah! I would snort all the coke and kiss all the boys—if I could live on Ho-Hos, Jack Daniel’s and pharmaceutical cocaine, I would (and not blow my brains out, ‘cause that’s exactly what I’d do). I have a completely addictive personality. Diet Coke is my last—God, I know people counting days off Diet Coke; I’m such a Diet Cokehead. Now I won’t let myself buy it. I’m sorta like the girl who only gets coke from boys—at parties I let myself have a Diet Coke with lime and it’s exactly like snorting a line. If a bomb goes off, I’m getting a carton of Marlboros.

There’s a notion of your being and celebrating the pistol-packing outlaw—a very Texan lack of adherence to convention—which addicts often resemble. But in recovery, the idea of surrender, of adherence to rules, is something people have to learn. How have you managed?

I used to think of it as an adherence to rules, and the really horrible thing about quitting drinking is, I think, inside my mind I was so divided against myself. Nobody really talks about what happens to you and your level of self-confidence when you tell yourself every fucking day you’re going to drink X, and then you drink 10 times that—or you’re not going to drink at all and you drink anyway. You become very split off against yourself. So there was a part of me that would yell and scream and say, “You stupid bitch, goddamnit, you said you weren’t gonna drink and you drank anyway.” And there was this other part that was like “Fuck those people! Fuck the rules!” you know, blah blah blah…

You assume that when you quit drinking, you’re surrendering to that kind of nasty schoolmarm rule-maker. But for me getting sober has been freedom—freedom from anxiety and freedom from…my head. What has kept me sober is not that strict rule-following schoolmarm. There’s more of a loving presence that you become aware of that is I think everyone’s real, actual self—who we really are.

Blake said, “we are put on Earth a little space that we might learn to bear the beams of love.” And I think, quote-unquote, “bearing the beams of love” is where the freedom is, actually. Every drunk is an outlaw, and certainly every artist is. Making amends, to me, is again about freedom. I do that to be free of the past, to not be haunted. That schoolmarm part of me—that hypercritical finger-wagging part of myself that I thought was gonna keep me sober—that was is actually what helped me stay drunk. What keeps you sober is love and connection to something bigger than yourself.

When I got sober, I thought giving up was saying goodbye to all the fun and all the sparkle, and it turned out to be just the opposite. That’s when the sparkle started for me.

Shares