Earlier this month, grassroots climate and anti-extraction activists in the Pacific Northwest scored a victory over one of the world’s most powerful industries. Kinder Morgan, an energy company that operates 26,000 miles of pipelines and owns 170 largely energy-related export terminals, announced it is scrapping plans to build a large coal export terminal on the Columbia River. The company has downplayed the role of community opposition to its terminal, claiming logistical considerations led to abandonment of the project. But local activists see more to the story than that.

Earlier this month, grassroots climate and anti-extraction activists in the Pacific Northwest scored a victory over one of the world’s most powerful industries. Kinder Morgan, an energy company that operates 26,000 miles of pipelines and owns 170 largely energy-related export terminals, announced it is scrapping plans to build a large coal export terminal on the Columbia River. The company has downplayed the role of community opposition to its terminal, claiming logistical considerations led to abandonment of the project. But local activists see more to the story than that.

Kinder Morgan’s decision to walk away from the Columbia came after months of steady grassroots opposition, and the company made the announcement two days after locals turned out in large numbers at a hearing to oppose the project. For environmental groups in the region, this looks like the culmination of a well-coordinated effort to protect communities along the Columbia from coal pollution.

“This announcement is great news for the Columbia Gorge and its communities who face the impacts of coal train traffic, coal dust and diesel pollution,” said Michael Lang, Conservation Director for Friends of the Columbia River Gorge, one of the groups that opposed the Kinder Morgan terminal. Along with other nonprofits like the Sierra Club, Columbia Riverkeeper, Climate Solutions, as well as a diverse coalition of volunteer-led community groups, Friends of the Gorge has been rallying citizens to speak out against the Kinder Morgan terminal and other proposed coal export projects in the region.

To reach Kinder Morgan’s terminal, which would have been located at the Port of St. Helens in Oregon, open-top trains carrying coal would have passed through the Columbia Gorge, exposing communities to pollution from coal dust and diesel fumes, holding up traffic in rail line neighborhoods, and raising the specter of a possible coal spill or train derailment in the Gorge. The terminal was designed to send up to 30 million tons of coal overseas each year.

It is one of several coal export terminals proposed on or near the West Coast since 2010, as the coal industry has turned its attention to energy markets in China, Korea and other countries across the Pacific. With coal demand declining in the United States, the industry hopes to flood the international market with its dirty product, tempting developing nations to build coal plants that lock them into decades of coal dependency.

But the industry isn’t exactly having an easy time of it, as coal export plans in the Pacific Northwest have encountered opposition from the start. When Australia-based Ambre Energy first announced in 2010 that it was seeking permits for a coal terminal in Longview, Wash., local environmental groups united to oppose the project. Landowners and Citizens for a Safe Community — a grassroots organization that got its start fighting liquefied natural gas pipelines — kicked into gear and began rallying local opposition. It was a preview of things to come, as the Northwest became ground zero in the fight over coal exports.

Ambre’s Longview project was the first of six coal export proposals to emerge in the Northwest. Backers of the projects have included Arch Coal, Peabody Energy, and Kinder Morgan. But communities have proven themselves capable of taking on some of the world’s most powerful energy companies. In fact, of the six coal export proposals originally on the table, three are now dead or indefinitely stalled.

The Kinder Morgan victory provides a good case study for how communities have been able to beat back the coal industry. Kinder Morgan announced plans to pursue the St. Helens project in January 2012. As in the case of the Longview terminal, the announcement triggered a backlash from affected communities — not only from the site of the proposed terminal itself, but also from towns and cities that would have seen increased coal train traffic had the project gone through. To bring coal to the St. Helens terminal, coal trains would likely have passed through Portland and other cities in Oregon, as well as dozens of towns in Montana, Idaho and eastern Washington.

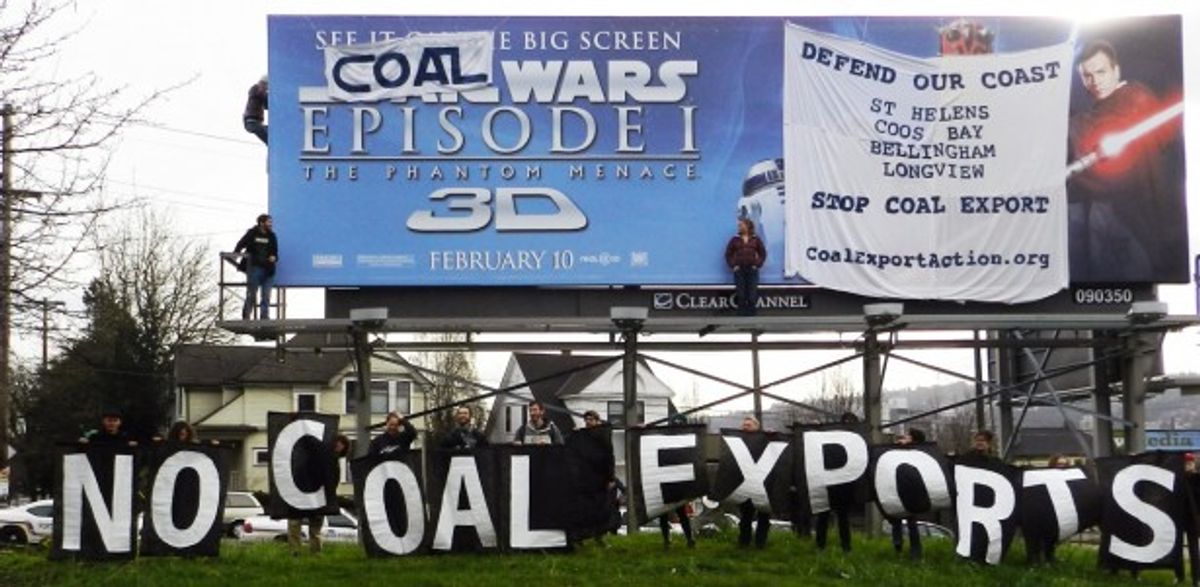

Attempting to bring coal trains through Portland may have been a particularly short-sighted move on Kinder Morgan’s part. “If Kinder Morgan had any pulse on public opinion around coal exports in Portland, they would know their project would be opposed every step of the way,” said Jasmine Zimmer-Stucky, an organizer with Portland Rising Tide. Along with other groups, Rising Tide has organized mass canvasses, guerilla flyering campaigns and creative direct actions like billboard modifications to alert Portland neighborhoods to the threat posed by coal exports.

Opposition to fossil fuels may not be surprising in green-leaning Portland, but Kinder Morgan soon found out it would encounter opposition at the site of the terminal as well. When the Port of St. Helens sought to rezone new port lands as industrial — a move seen by many as designed to ease the way for Kinder Morgan — the Sierra Club and other groups turned out 100 locals at a hearing to oppose the rezoning. Two days later, the company announced it was shelving the coal export project.

“This decision translates into healthier air and water for Oregonians,” said Dr. Andy Harris of Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, in response to the announcement. “It means there will be fewer patients with asthma, lung cancer, heart disease, strokes and sleep disorders in affected communities. We’re celebrating a victory for public health today.”

Kinder Morgan’s announcement came barely more than a month after another a coal export project in Coos Bay, Ore., was tabled. Had the terminal been built, it would have meant coal trains passing through Eugene, Ore., where citizens formed a grassroots group called No Coal Eugene.

A third West Coast coal export project died last summer, when RailAmerica dropped plans to build a coal terminal at the Port of Grays Harbor in Washington. That leaves three proposed terminals still on the table: the Longview project, which is backed by Ambre Energy and Arch Coal; Peabody’s Gateway Pacific Terminal in Bellingham, Wash.; and a project at the Port of Morrow, Ore., also backed by Ambre Energy.

The Longview and Bellingham projects are both the largest and the longest-standing West Coast coal export proposals, and would each handle about 50 million tons of coal per year. That’s almost five times what the largest coal-fired power plant in North America — the Robert W. Scherer plant in Georgia — burns annually. The Port of Morrow project is smaller, but would still produce an alarming 8.8 million tons of coal per year.

All three projects have drawn heavy opposition. Last fall, hundreds of Oregonians turned out to hearings on the Port of Morrow project, convened by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. Thousands attended hearings in Washington about the Pacific Gateway project, held by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Since the Army Corps is a federal body, tens of thousands of people from around the country — though mainly in the Northwest — submitted comments opposing Gateway Pacific. Ranchers whose lands would be impacted by coal mining came from as far away as eastern Montana to speak out against the project at an Army Corps hearing in Spokane, Wash.

“At the hearings about coal exports in the Portland area, sometimes as many as 800 people showed up to express opposition,” said Rodger Winn, a volunteer activist with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign. “The Oregon DEQ had to change venues because so many people showed up to testify.”

Of course, the fight against Northwest coal exports isn’t over yet — and it won’t be, until all three remaining projects are defeated. For now the abandonment of Kinder Morgan’s terminal has allowed local activists to focus on the remaining coal projects in the region, while some groups simultaneously expand their focus to other fossil fuel export infrastructure.

“For folks along the Columbia River,” said Rising Tide’s Zimmer-Stucky, “having Kinder Morgan walk away allows us to put all our energy into fighting Australia-owned Ambre Energy, which is behind both of the remaining projects on the Columbia.”

In addition to the Longview, Bellingham and Morrow coal projects, energy companies are looking to export oil and liquefied natural gas through West Coast ports. There are currently five proposed or existing oil export terminals in the Pacific Northwest. Rising Tide is looking to harness some of the momentum from Kinder Morgan’s defeat to build a broader movement against fossil fuel exports of any kind, expanding its scope to include oil infrastructure as well.

The defeat of Kinder Morgan may also serve as an inspiration for climate activists fighting fossil fuel projects elsewhere in the United States, such as mountaintop removal, fracking and tar sands pipelines. “That Kinder Morgan scrapped plans for the St. Helens terminal is a testament to the power of communities to stand up and make a difference,” said Stephan Michaels, a freelance writer and journalist who has written about coal exports for the Seattle Times. “This latest coal port being dumped might continue a much larger domino effect.”

Nick Engelfried is an environmental writer and activist. He is currently an organizer for the Blue Skies Campaign in Missoula, Montana.

Shares