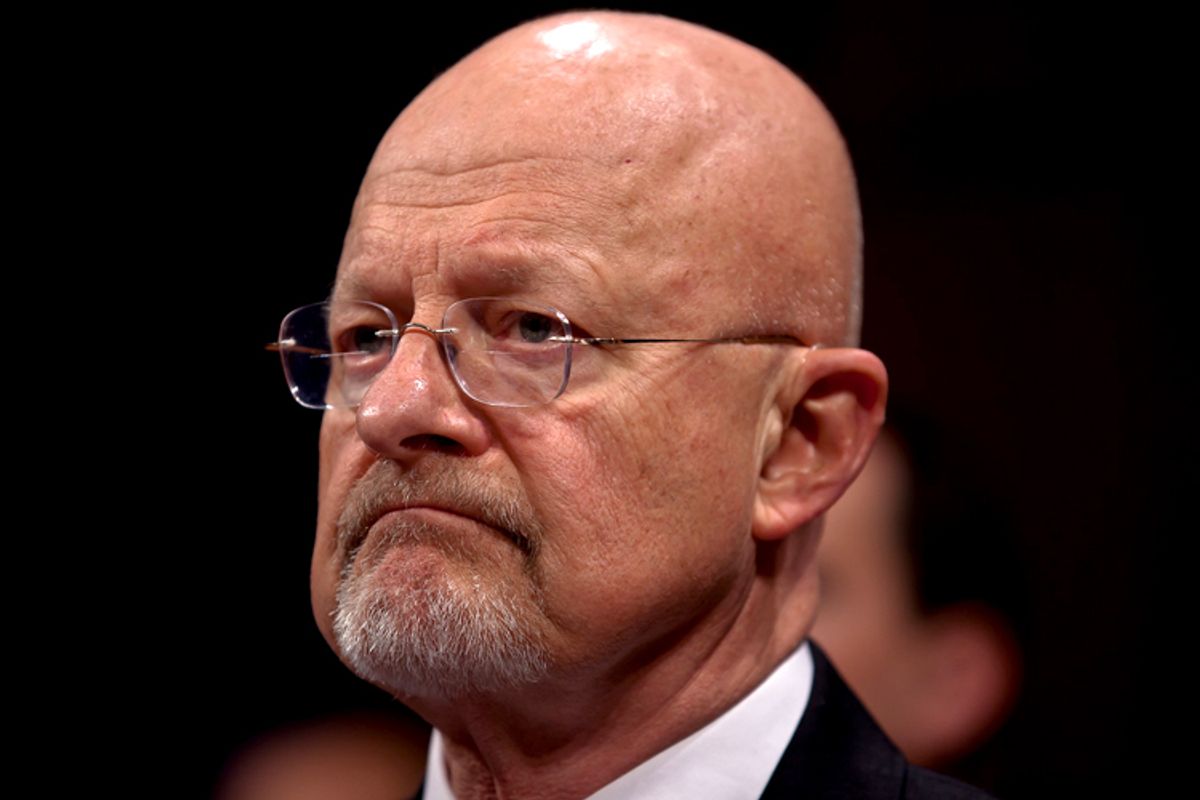

Did National Director of Intelligence James Clapper commit perjury when he testified before the Senate in March? The answer to this question isn’t as straightforward as it appears to be. As a practical matter, however, it’s the wrong question to be asking about Clapper’s behavior.

Clapper was asked by Sen. Ron Wyden, “Does the NSA collect any type of data at all on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans?” Clapper responded, “No, sir … not wittingly.”

Now this is what an ordinary person would call a “lie.” Ordinary people also believe that perjury is lying under oath. But lawyers are not ordinary people, and, as a technical legal matter, the situation is more complicated.

If the question of whether Clapper committed perjury is understood to mean, “Would the government (if it were inclined to prosecute Clapper, which it won’t) be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Clapper’s response violated the federal perjury statutes?” the answer is, “Maybe, maybe not.”

Legally speaking, perjury is hard to prove, because it’s a highly technical offense. As a matter of federal law, a witness commits perjury if he knowingly makes a false material statement under oath. Clapper was under oath, his statement was false, and it was material to a legitimate governmental investigation. (The materiality requirement is intended to eliminate so-called “perjury traps,” in which a witness is asked a question for no other reason than to try to get him to perjure himself.)

Nevertheless, the government would not have a slam dunk perjury case against Clapper, if it chose to prosecute him. This is because, to secure a perjury conviction, the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the witness knew his statement was false. No doubt relying on the advice of counsel, Clapper has already deployed what could be called the “it depends on what the meaning of ‘collect’ is” defense.

In an interview with NBC’s Andrea Mitchell, Clapper used a metaphor for what the intelligence services are doing, in which he compared gathering information about phone conversations, as opposed to actively listening to those conversations, to tracking the Dewey Decimal System numbers of books on a library shelf, as opposed to actually reading the books:

To me, collection of U.S. persons’ data would mean taking the book off the shelf and opening it up and reading it ... And this has to do with of course somewhat of a semantic, perhaps some would say too – too cute by half [definition]. But it is – there are honest differences on the semantics of what, when someone says ‘collection’ to me, that has a specific meaning, which may have a different meaning to [Sen. Wyden].

Now this strikes me as an extremely implausible defense, especially in response to the question “Does the NSA collect any type of data at all on millions of Americans,” which in retrospect was obviously phrased by Sen. Wyden in this way in an attempt to stop Clapper from engaging in what even Clapper admits sounds like disingenuous semantic quibbling. (It’s also worth noting that Sen. Wyden provided Clapper with the questions he would be asked the day before the hearing, and gave him an opportunity the day afterward to modify or retract any of his testimony.)

But just because a defense sounds implausible, that doesn’t mean it can’t be successful. Clapper would merely need to raise a reasonable doubt in one juror’s mind regarding whether he knew his statement was false. Would he be able to do so? That’s what Washington’s top white-collar criminal defense lawyers are paid $800 per hour to find out.

But in the end, that question should be irrelevant to the real question of the moment, which is whether there’s a good enough basis for concluding that Clapper lied to the Senate under oath, with “good enough” here meaning “good enough for the purposes of firing him.”

That is not – nor should it be -- a technical question of criminal law, and you don’t have to be a lawyer to recognize that the answer to it is obvious.

Shares