It has been a season of literary takedowns, but then it usually is. You can always get a rise out of the otherwise lethargic reading public by launching an offensive against one of its icons. In the past two months alone, we have had Kathryn Schulz disliking "The Great Gatsby" in New York magazine, Christian Lorentzen's salvo against Alice Munro in the London Review of Books, and Joseph Epstein in the Atlantic Monthly, asking, "Is Franz Kafka Overrated?"

The great thing about such essays from an editor's perspective is that they make one portion of the readership angry enough to quarrel with the critic in the comments thread and beyond. Meanwhile, another portion is enthusiastic to an almost equal degree at having their privately held reservations finally voiced in a public forum. Still other readers can, like high school students, be counted upon to cluster around any promise of a fight. Emotions run high, which is the journalist's brass ring and pretty hard to come by in discussions of literary topics.

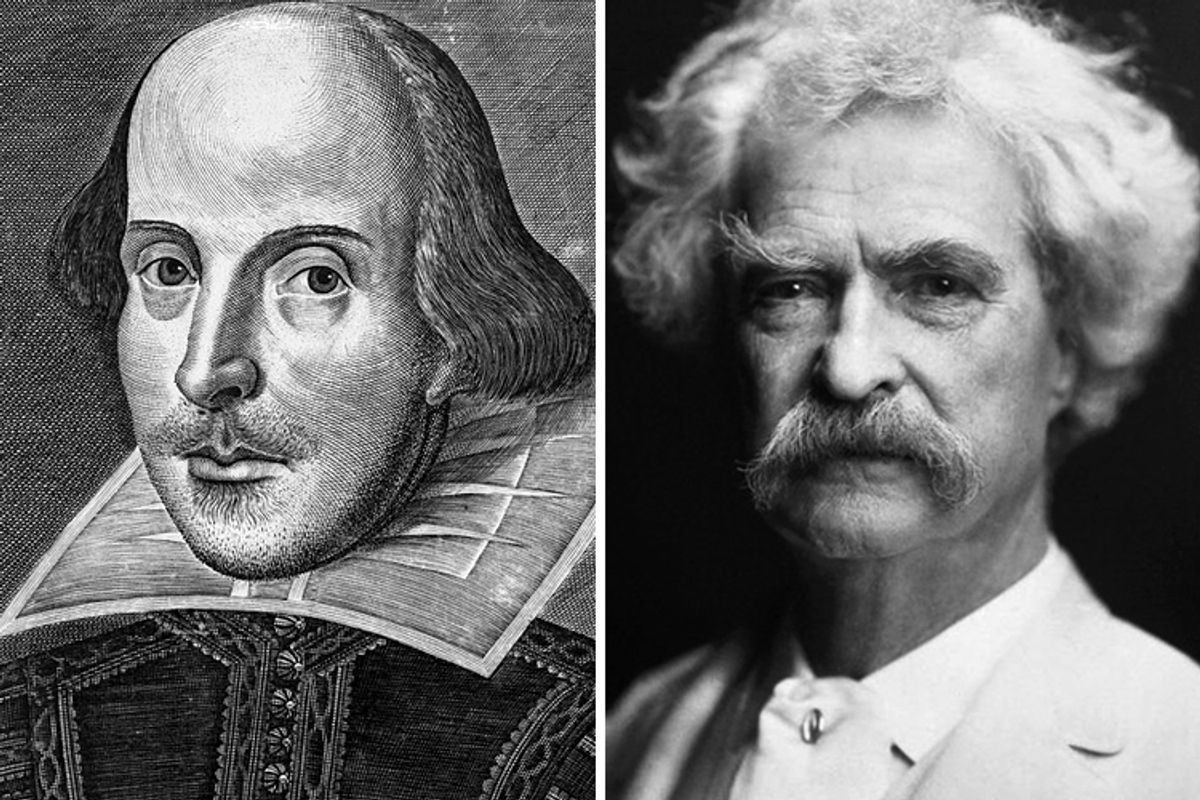

For this reason, the literary takedown has a long and storied history. Perhaps the most celebrated of them all is Mark Twain's hilarious "Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses," a flamboyant drubbing of the early American author of wilderness adventure novels. Surveying "The Deerslayer," Twain observes that "in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record," and then goes on to list the "nineteen rules governing literary art in the domain of romantic fiction," 18 of which Cooper has violated.

"When you strike at a king, you must kill him," Ralph Waldo Emerson warned Oliver Wendell Holmes when Holmes, then a college student, sent him a paper in which he railed against Plato for "loose and unscientific" thinking. A corollary to Emerson's advice: If you've got to strike somebody, don't pick on the serving lad; that only makes you look like a bully. A good literary takedown selects its target with care. If Cooper was not quite a king, he did enjoy a good amount of popularity and critical respect, the latter of which Twain demonstrates by opening his attack with three examples of praise Cooper had received from professors and another novelist (Wilkie Collins).

To kill him, Twain offers a highly detailed dissection of the physical impossibilities represented in one of Cooper's action scenes and several other instances in which the novelist was "splendidly inaccurate." But Twain was not merely pedantic on practical matters related to sharpshooting and riverine navigation. He was also, as ever, funny -- declaring, of Cooper's uneven dialogue, "when a personage talks like an illustrated, gilt-edged, tree-calf, hand-tooled, seven-dollar Friendship's Offering in the beginning of a paragraph, he shall not talk like a negro minstrel in the end of it."

Exasperation, rather than flaming rage, is the emotion that drives the best takedowns. A certain distance also helps. A pan of a single novel that has otherwise been admiringly reviewed and is by an author currently in his or her prime, doesn't really count. First, living authors are never as revered as the dead kind, so the critic lacks the moral high ground obtained by attacking a sacred cow. Furthermore, many a great writer has produced a mediocre book, and a takedown ought to encompass an entire career, even if it chooses to focus, as Twain did, on one exemplary title. Lastly, since so many critics are novelists themselves, an assault on the reputation of a living competitor, especially one who's near the attacker in age, will usually be read as motivated by feelings of professional resentment and rivalry.

Some takedowns, written by young critics about a living author relatively late in his or her career, amount to generational shots across the bow. That's what Lorentzen seems to have been attempting in complaining that, in contrast to "the consensus around Alice Munro," he finds her short stories drab, repetitive and excessively "sad." It's what David Foster Wallace was clearly up to in 1997, when he reviewed one of John Updike's disposable late novels in a piece given the headline "John Updike, Champion Literary Phallocrat, Drops One; Is This Finally the End for Magnificent Narcissists?" It was Wallace's way, à la Harold Bloom's "The Anxiety of Influence," of clearing some space for the new kids in town.

But the true, ninja-grade takedown must be mounted against an undisputed great. It requires the ego of a George Bernard Shaw to write of Shakespeare, in the Saturday Review, as "this 'immortal' pilferer of other men's stories and ideas, with his monstrous rhetorical fustian, his unbearable platitudes, his pretentious reduction of the subtlest problems of life to commonplaces against which a Polytechnic debating club would revolt, his incredible unsuggestiveness, his sententious combination of ready reflection with complete intellectual sterility, and his consequent incapacity for getting out of the depth of even the most ignorant audience, except when he solemnly says something so transcendentally platitudinous that his more humble-minded hearers cannot bring themselves to believe that so great a man really meant to talk like their grandmothers." Whew!

Sniping -- tossed off nasty remarks -- is cheap and does not count, otherwise Lord Byron would be the Lord of Takedowns, so jam-packed are his letters and journals with passing jibes: "Chaucer notwithstanding the praises bestowed on him, I think obscene, and contemptible, he owes his celebrity merely to his antiquity." I would have liked to see him back that up as well as Twain supported his dethroning of Cooper. Somewhere in between fall such phenomena as Nabokov's imperious dismissals of the many authors he found sub-par, most notoriously Dostoyevsky. Nabokov always behaved as if his own aesthetic judgments were as self-evident and immutable as the Second Law of Thermodynamics. (A student taking his course on Russian literature became so irate at Nabokov's refusal even to discuss Dostoyevsky that he demanded that he be allowed to teach that session himself. Nabokov stormed into the administrator's office and tried to have the student expelled.)

The most serious-minded takedowns detect a moral failing in the putative giant. Bertrand Russell, with a confidence that rivals Shaw's, assailed no less a figure than Socrates in his wonderful (and deliciously readable) "A History of Western Philosophy," writing, "He is dishonest and sophistical in argument, and in his private thinking he uses intellect to prove conclusions that are to him agreeable, rather than in a disinterested search for knowledge. There is something smug and unctuous about him, which reminds one of a bad type of cleric."

This is more or less the tack taken by Schulz in explaining her inability "to derive almost any pleasure at all" from "The Great Gatsby." Hers is by far the most thoughtful and most carefully articulated of the recent takedowns, which is obvious whether or not you agree with her when she writes, of Fitzgerald, "when you apply a strict moral code to the saturnalian society to which you are attracted -- you inevitably wind up a hypocrite."

As for Lorentzen and Epstein, their complaints about Munro and Kafka are notably similar. Each finds the worshiped author's work depressing and just too samey. It could be argued that neither Munro nor Kafka ought to be read in long binges, and that one might as well grouse that you can't make a proper meal out of caviar. Lorentzen, at least, shows his work, and you can understand how any short story writer's bag of tricks, however artfully employed, can seem a bit shopworn by the time you've closed the 10th volume of her work. Chekhov, even, might begin to pale.

Epstein has no comparable excuse for moaning that Kafka's stories are "distinctly not a jolly way to start the day," as well as too uniformly Freudian and "hopeless." His real beef, however, is with Kafka's champions for refusing to provide a sufficient "explanation" for the fiction and instead insisting that it must simply be "experienced." C.S. Lewis (no Freudian, that's for sure!) admired Kafka almost exclusively among modernist writers for precisely this reason. He thought Kafka's work obtained the quality of "myth," by which he meant a story whose meaning is precisely itself: "I feel a profound significance but it emanates from the whole story and is not built up by understanding the parts, nor could I state it except by retelling the story ... of course, the two things are not absolutely separable."

Not everybody finds this sort of fiction to their liking, however, as Lewis himself acknowledged. So perhaps the most judicious takedowns are less rants than shrugs. "There are people who cannot taste olives," wrote William Hazlitt, "and I cannot much relish Ben Jonson, though I have taken some pains to do it, and went to the task with every sort of good will. I do not deny his power or his merit; far from it; but it is to me of a repulsive and unamiable kind."

The contemporary critic Geoff Dyer wrote much the same of David Foster Wallace's work two years ago. He wants to like it, he really does, but, "a page -- sometimes even a sentence, or an essay title -- brings me out in hives." He goes on to acknowledge with laudable honesty, "This is not a literary judgement; I have not been able to read enough of him to form one." Instead, Dyer concludes that he has a "literary allergy. This should not be confused with a negative value judgment; it is simply a reaction."

So mature and reasonable! Perhaps no literary takedowns would be necessary if we didn't live in a world in which so many of us have been obliged, at one point or another, to read books that disagree with us in exactly this way. Nevertheless, a sound attack, even on an author you love, can be surprisingly illuminating, forcing the fan to do more than gush and the critic to do more than genuflect. Besides, the world might well be a better place without "The Deerslayer," but it would be an awful lot poorer without "Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses."

Further reading

"Is Franz Kafka Overrated?" by Joseph Epstein for the Atlantic Monthly

"Poor Rose," an essay on Alice Munro by Christian Lorentzen for the London Review of Books

"Why I Despise The Great Gatsby" by Kathryn Schulz for New York magazine

"Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses" by Mark Twain

"John Updike, Champion Literary Phallocrat, Drops One" by David Foster Wallace for the New York Observer

"My Literary Allergy" by Geoff Dyer for the Prospect

Shares