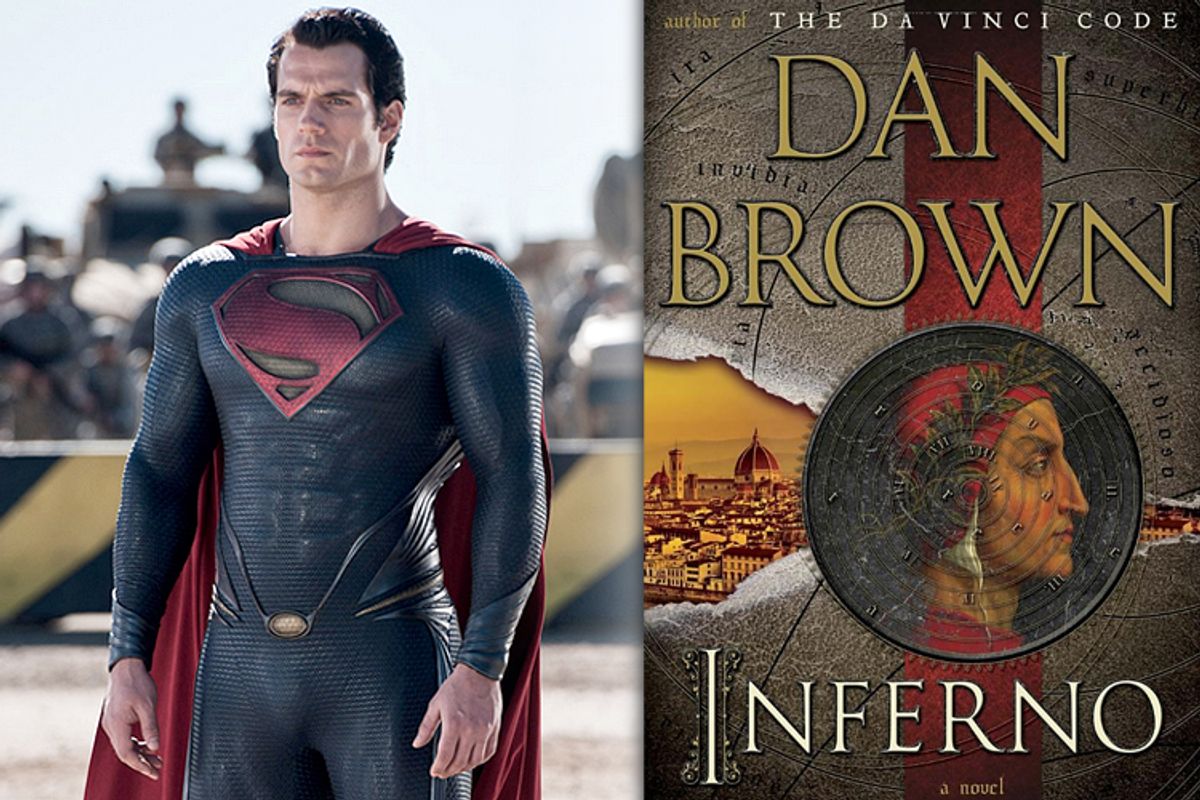

This past May, the fourth novel in Dan Brown’s Robert Langdon saga, "Inferno," hit shelves. June saw the release of the anticipated "Man of Steel" in theaters nationwide. At first glance, these two cultural products have little in common except for, perhaps, the hype they’ve generated among their respective fans. But close reading reveals that both touch on one major contemporary issue: overpopulation.

In "Inferno," Brown’s renowned Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon is off crusading again to save the world from a cataclysmic disaster. Readers and critics alike might find themselves wondering: “So, what else is new?” But the upcoming conflict engages with some fascinating, albeit ominous, issues. The “bad guy,” a famous geneticist named Bertrand Zobrist, whose obsession with the work of the 13th century Florentine writer Dante Alighieri is more than apparent throughout the story’s twists and turns, is against many global measures seemingly aimed at improving human existence. His nemesis in the novel is the World Health Organization, and more specifically, its director Elizabeth Sinskey, with whom he first discloses some of his more “radical” persuasions. With Langdon’s help, Sinskey and her allies spend the majority of the novel trying to keep Zobrist from executing his plan.

In addition to being obsessed with Dante’s work – and the Renaissance artwork depicting it – Zobrist is also infatuated with, and oddly appreciative of, the outbreak of the bubonic plague during the 14th century: the so-called Black Death. He is also certain that the global population level is rising far too fast, without a corresponding level of natural resources to sustain it, and his critique of the WHO’s measures to combat disease are notably unsympathetic: They should cut it out, he argues. “Dr. Sinskey, you talk about controlling epidemics as if it’s a good thing,” he scolds her.

For Zobrist, the Black Death was nature’s way of correcting an imbalanced ratio of human growth: There were far too many people, most of whom were living filthy, wretched lives, and the plague relentlessly kept it all in check by reducing the population to as low as 50 percent its size in some of the more congested cities. Zobrist is ideologically bent on forcing nature to correct the repeat imbalance that has escalated ever since, and after his year-long disappearance, dramatic suicide in Florence, Italy, and the subsequent appearance of his cryptic, Dante-plague-themed messages he left behind, Sinskey fears that the talented geneticist has set something horrible in motion: a fabricated über-plague, meant to wipe out most of the earth’s population in accordance with Zobrist’s own vision for saving humanity and securing its evolutionary future.

So where does Superman fit in to all of this? About an hour into the new film, the preserved consciousness of the late Jor-El, the father of Kal-El/Clark Kent, appears to his grown son as a hologram aboard an old ship from his home planet of Krypton. Viewers discover, along with Jor-El’s estranged child, the circumstances that influenced his decision to send Kal-El away from Krypton, giving their people a chance to persevere: The planet was moments away from collapsing into a self-destructive, cosmic event. Shortly after Kal-El’s vessel left Krypton’s atmosphere and began its journey to Earth, Krypton exploded into innumerable fragments across the dark, galactic horizon.

The details surrounding Krypton’s destruction, however, are particularly relevant to an examination of Brown’s "Inferno." What Jor-El discloses to his grown son is that Krypton’s population had grown at an alarming rate in the years leading up to its destruction. The planet’s natural resources had been depleted, and Krypton’s core had been growing more and more unstable as the years passed. The Kryptonians were forced to order a fleet of scouts to traverse the universe, searching for a suitable location for a new “Krypton.” As the missions were eventually abandoned, and Krypton’s core grew increasingly unstable, population control efforts were implemented in an effort to curb a planetary disaster. Natural births became a relic of the past. Children were born in a “birthing matrix,” by means of a genetic, Kryptonian codex. Each of them was born with a specific career and life-path already planned (viewers may be reminded here of literature from the second half of the twentieth century with a similar sort of futuristic societal structure). Kal-El’s birth was the first natural birth in years, and his parents inserted the genetic codex into his cells before sending him on his way, effectively giving him the means to re-birth the Kryptonian race.

The messianic dimensions surrounding Kal-El’s journey to Earth and revealing himself “when the world is ready,” as his adoptive father advises, have already received significant analysis. What I want to focus on, however, is the relation this messianic figure has to the critique presented by Zobrist in Brown’s "Inferno," and the power it has to symbolically prevent another planet from suffering a similar sort of fate.

The unfortunate truth is that our planet is nearing a similar state of crisis – one that is becoming increasingly irrevocable with each passing year. This past May, we exceeded 400 parts per million (PPM) of atmospheric carbon; experts maintain that anything above 350 PPM (which we exceeded over 25 years ago) is simply unsustainable. The planet is reportedly growing warmer every year, and the consumption of its limited resources, by an ever-increasing population, is doing relatively little to allay the situation. According to the United States Census Bureau, the global population is currently an estimated 7.093 billion people. The world should see 8 billion by around 2025, and perhaps 9 billion by 2050.

But how do these statistics compare with what analysts maintain is a sustainable global population – one in which poverty and starvation, along with horrendous living conditions and sanitation, are minimized to marginal levels? “Any environmental biologist or statistician will tell you that humankind’s best chance of long-term survival occurs with a global population of around four billion,” Zobrist chides Sinskey during their first meeting in "Inferno." She takes that number quite poorly -- understandable considering the current population is almost double that figure. But Zobrist’s assertion echoes the work of scientists such as David Pimentel, whose research within the past couple of decades locates a comfortable, sustainable global future between 1 and 3 billion people – a bit less than what this fictional, wide-eyed geneticist has predicted.

Zobrist reminds Sinskey that entire species are going extinct at accelerating rates, and the demand for natural resources and clean water in many areas of the world is alarming. The WHO’s response to these types of issues? Find cures, battle deadly diseases, and prolong life. Zobrist’s proposition for a change of course in the WHO’s directives is obviously not well-received. While there are certainly other variables to consider, such as mortality rates and birth rates, it is indisputable that our population is growing, and that we may or may not be approaching a level that simply cannot sustain itself. In fact, on June 25, President Obama’s administration released his action plan to “reduce carbon pollution, prepare the U.S. for the impacts of climate change, and lead international efforts to address global climate change.” “We can choose to believe that superstorm Sandy, and the most severe drought in decades, and the worst wildfires some states have ever seen were all just a freak coincidence,” he states, “Or we can choose to believe in the overwhelming judgment of science – and act before it’s too late.” As one who was living very close to where Sandy hit the New England coast last year, and as one who is now living among the fires spreading throughout Colorado, I would implore those listening to embrace his warning and finally heed such a call to action.

What I think audiences can take away from books like "Inferno" and films like "Man of Steel" is not that we need to drastically halt the growth of our population with a plague, but that we more deeply consider the real-world issues that can end up tearing our planet apart in Kryptonian fashion. Should we stop treating those with curable ailments, praise the existence of diseases such as cancer, as Zobrist might have us do, or hope that something like AIDS might one day go airborne? Probably not. However, we should be taking seriously the fact that while many of us live relatively comfortable lives, divorced from daily struggles of starvation and sanitation, there are many areas throughout the world that vividly recall the incongruous slump of diseased and hungered bodies depicted in late medieval and Renaissance art. The nuclear family ideal is a pleasant one to have, but the reality is that times change, and so does the sustainability of our current context.

Readers of Dan Brown’s "Inferno" were relieved to discover that Zobrist was not so cruel as to unleash a mega-strain of the bubonic plague, as they might have feared. His airborne (and successful) viral attack on the global population was much more innovative: a vector virus that randomly renders one in every three people sterile. Zobrist may be the villain of the book, but he did seem to take care of the global problem, and he did so in a much more humane way than simply infecting everyone with a horrible disease and forcing most to suffer an excruciating last few days of life (extinction was never his goal, as his “transhumanist” ideals simply drove him to desire a world in which humanity could properly evolve, uninhibited). Humans are unlikely to decide, en masse, to stop reproducing, and Zobrist made that decision for them.

There are clear ethical problems with Zobrist’s actions. Regardless of whether or not his intentions were dictated by what he perceived as “right,” he still violated the freedoms and liberties of the global population – in likely an irrevocable way, readers discover. If the global population could not be convinced to voluntarily reduce its procreation to more sustainable levels, would that give anyone the right to make such a decision for them? Real-world correlations to such concerns certainly exist; readers might recall recent reports this week of sterilization of inmates at California state prisons, and America already has a long and troubling history of sterilizing poor and minority citizens. Zobrist’s transhumanist ideological bent also placed him in a biased position, in terms of what is “best” for humanity. Why should we elevate his values and beliefs over other ideologies and worldviews? What makes his perspective more legitimate than others? Clearly, these are highly sensitive questions that don’t easily yield the simplest of answers. But, can we get around the inherent controversial nature of these issues and attempt to interpret the messages of these two popular cultural artifacts in a more sustainable way – one that doesn't involve a sterility virus or some sort of Kryptonian "birthing matrix"?

Although the “correct” approach remains to be determined, the symptoms of inaction cannot be avoided, and Zobrist did engage these concerns, albeit not in a way most humans would prefer. In “Natural Resources and an Optimum Human Population” (1994) Pimentel et al. writes, “to do nothing to control population numbers is to condemn future humans to a lifetime of absolute poverty, suffering, starvation, disease, and associated violent conflicts.” Kal-El, then, might serve as a symbol for the path humanity must take to prevent its own self-destruction. Thus, Krypton serves as the warning, and Kal-El symbolizes our ability to prevent a similar sort of fate. Zobrist’s tactics were extreme, but they take that warning and embrace Kal-El’s messianic message: Without proactive assessments and serious considerations, we might also find ourselves searching the dark horizon for a new “Earth” somewhere beyond our immediate reach.

Shares