[THIS STORY HAS BEEN UPDATED]

I just got off a conference call promoting the "sharing economy" put on a by a new nonprofit organization called Peers. The call featured a couple of writers who are big proponents of the sharing economy, Lisa Gansky and Rachel Botsman; an academic, Arun Sundarajan; a Lyft driver; an AirBnB host; and an ordinary citizen who consumes several sharing services.

They all had uplifting things to say about what Peers.org director Natalie Foster touted as the "defining economic story of the 21st century." The sharing economy will build trust between people, reduce resource consumption, and stretch tight pocketbooks.

All that may well be true. There are aspects of the sharing economy that are cool and exciting. But the speakers devoted nearly all of their prepared statements to the benefits the sharing economy delivered to the consumers and producers linked together by these services, and very little attention to the services themselves -- the venture-capital-funded platforms that are looking to reap significant financial rewards from all this "sharing." (A more accurate description, suggested by former Wired technology writer Ryan Singel, might be "subletting." Money, after all, does exchange hands when you share your car or guest bedroom. But the "subletting economy" doesn't sound anywhere near as sexy.)

The distinction between platforms and consumers is important, because rosy-hued descriptions of how the sharing economy will lead to a better world where we consume less and trust our neighbors more tends to obscure the fact that venture-capital-funded, profit-seeking organizations are providing a significant amount of the impetus for the spread of sharing economy services. For the platforms, "trust" is just another marketing buzzword.

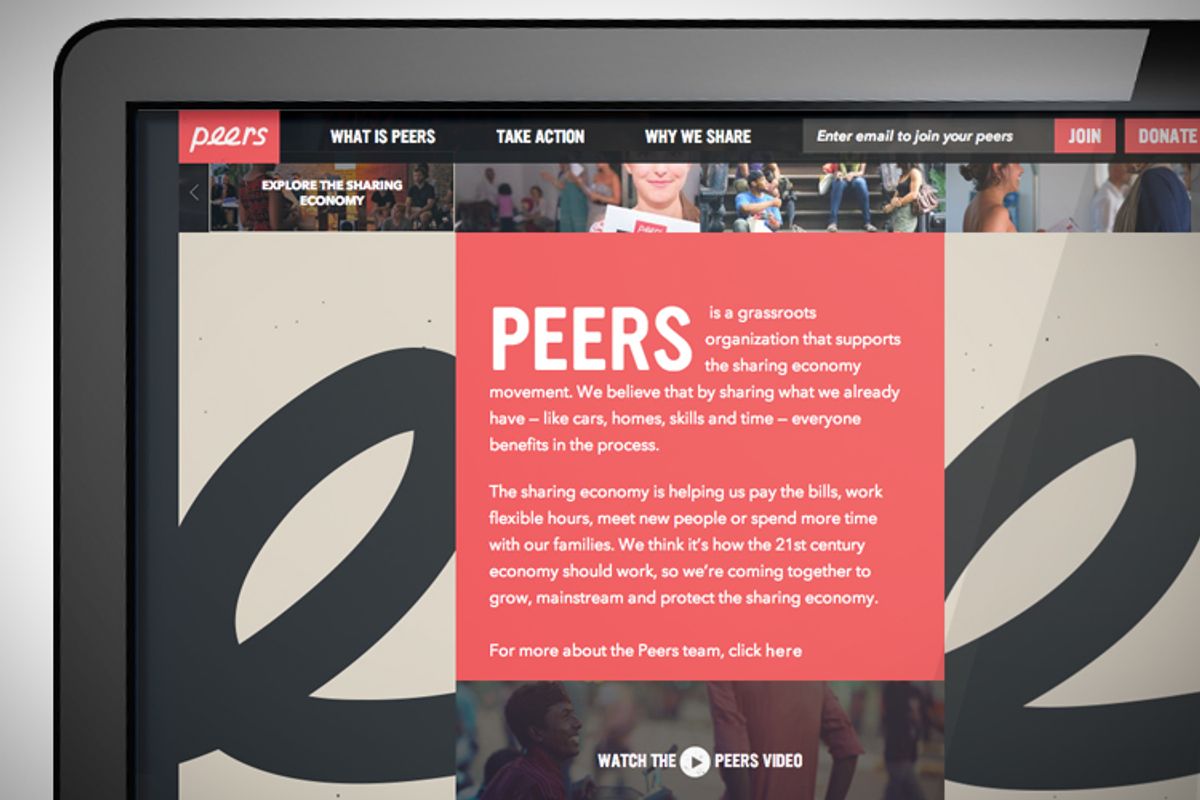

So the obvious question is, who does Peers represent? Natalie Foster described Peers as a "grassroots organization" aiming "to grow the sharing economy." But some probing questions from a Bloomberg reporter on the call quickly established that "grassroots" might not be the best word to describe Peers. Foster eventually admitted that Peers was launching with 22 partners, among whom were a number of companies operating in the sharing economy space. Although initially seeming a little reluctant to answer the question of who was paying for Peers, she also eventually acknowledged that the 22 partners were also helping to fund the operation.

Natalie Foster is a veteran of President Obama's digital team, and has also worked for the Sierra Club and MoveOn.org. So her progressive credentials look pretty solid. But her exchange with the Bloomberg reporter raised more questions than it answered. One of the primary missions of Peers, said Foster, was to help "protect" the sharing economy and advocate for it. For example, Peers might help its members ask the mayor of a city for a bike-sharing program, she said. But at the same time she also stressed explicitly that Peers was not a "lobbying organization."

I don't know how one decides when asking a mayor for something is lobbying and when it isn't, and I really don't know how the word "grassroots" applies to an organization that is at least partially funded by industry players.

But I look forward to learning more.

UPDATE: Natalie Foster says that the launch partners are not directly financially supporting Peers. My full story is here.

Shares