What is a fantasy, exactly?

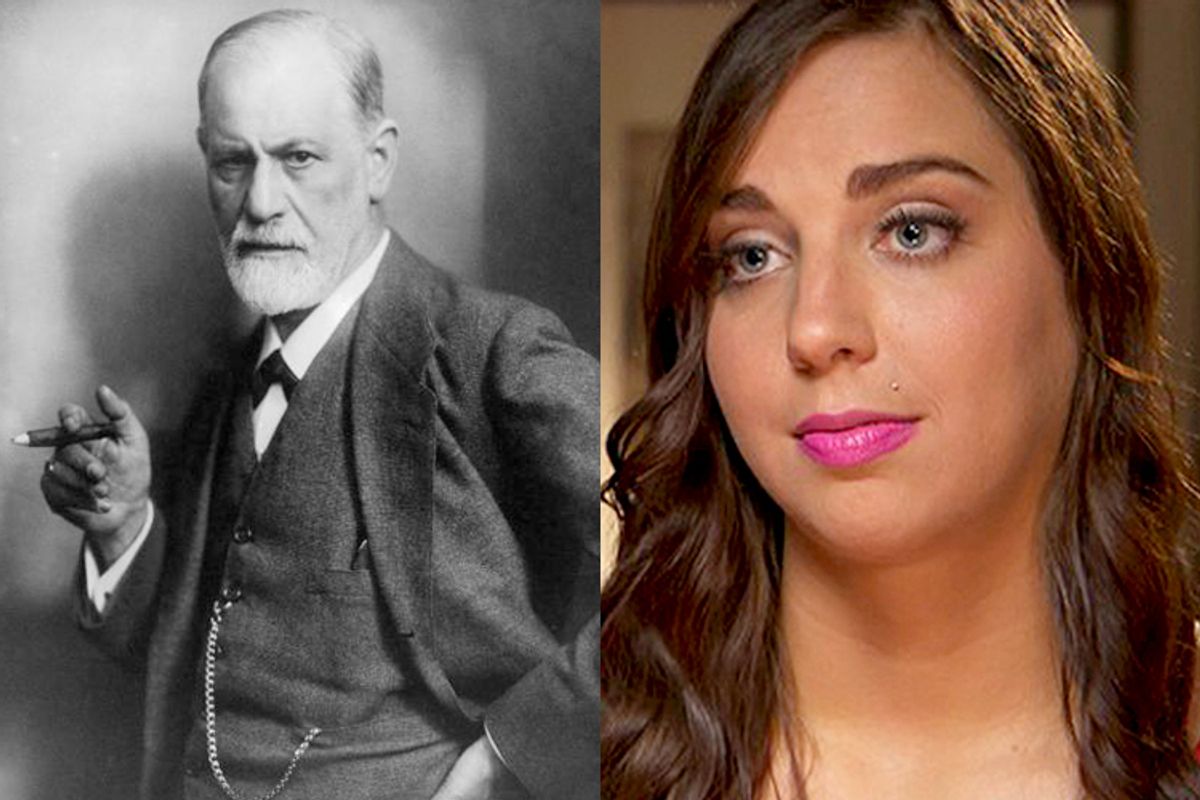

As we might expect, the question shows up frequently in the work of Sigmund Freud. In their 1968 essay “Fantasy and the Origin of Sexuality,” Jean Laplanche and J.B. Pontalis note that “From its earliest days, psychoanalysis has been concerned with the material of fantasy.” And like most of the things Freud was greatly interested in, his views on the topic shifted quite a bit. In contrast to the general picture of Freud as a stubborn dogmatist, his theoretical writing actually shows a remarkable fluidity and a willingness to modify his positions rarely equaled by world-renowned thinkers. But I digress.

Fantasy is frequently understood, even by Freudians, in the same terms in which Susan Jacoby’s recent Op-Ed on Anthony Weiner seems to grasp it, in opposition to truth. There is a basic concrete reality to the world, and fantasy, in this logic, is a pale imitation of this world, a “virtual” copy of it: As Jacoby writes, “Virtual sex is to sex as virtual food is to food: you can’t taste, touch or smell it, and you don’t have to do any preparation or work.” There’s something distinctly quaint about this idea of sexting: The idea of “virtual sex,” like the idea of “virtual reality,” dates back to an era, some 20 years in the past, in which the Internet was a fad for undersexed geeks and not a fundamental infrastructure of the global economy. In this logic, as Laplanche and Pontalis summarize it, “The world of fantasy seems to be located exclusively within the domain of opposition between subjective and objective, between an inner world, where satisfaction is obtained through illusion, and an external world, which gradually, through the medium of perception, asserts the supremacy of the reality principle.”

One thing that remains consistent in Freud's speculations on fantasy is its link to the reality principle. The reality principle provides the psyche with what we might today call “a reality check”: It examines the world to make sure that the image of it that exists in the individual’s mind reflects the actual order of things. The reality principle, properly functioning, helps ensure that our actions are a response to the world as it is and not to the world as we might like to imagine it; when the reality principle misfires, the result is delusion or delirium: psychosis, for Freud, is a “retreat from reality in the service of the id” (“Neurosis and Psychosis,” 1923).

The reality principle also helps us distinguish which objects of desire are attainable and which are not. Here, again, the true/false model of fantasy would reduce reality to simple availability: You masturbate to porn when the person you actually want to sleep with isn’t there. This notion in turn links fantasy with an entire array of value judgments: Fantasy is fake, it’s not “the real thing,” it’s not as good, it’s not as satisfying. Or, as in Jacoby’s case, fantasy is judged by way of a Calvinist work ethic: “You don’t have to do any preparation or work,” as Jacoby notes; fantasy is a form of laziness for people who want all the satisfaction with none of the effort. If you were serious about wanting sex, you’d get up and invest the time and work to make it actually happen.

But Freud understands fantasy very differently. In psychoanalysis, fantasy is not simply a pale imitation of the individual’s relationship to the real world; it is an entirely different relationship, to an entirely different world: “The opposite of play is not seriousness but reality.”

When Freud writes that the reality principle tells us which objects of desire are attainable and which are not, he means this in two fundamentally distinct senses, because, in the framework of psychoanalytic theory, there are two different ways in which an object can be unavailable, two distinct orders of wish-fulfillment: When the reality principle asserts that you can’t have sex with your parents because of the cultural prohibition against incest, it's making a fundamentally different assertion than when it asserts that you can’t have sex with a unicorn. An object can be unavailable because it doesn’t exist in reality, or an object can be unavailable because the desire for it is prohibited, and our desires respond very differently to each condition: In the case of the prohibited object, the mind says, That thing exists, and I can’t have it; desire is constrained, frustrated. These frustrations, in turn, produce repression and neurotic symptoms. In the case of the unreal object, the mind says, That thing doesn’t exist, and therefore I can fantasize about it with no consequences. Or, to put it slightly differently, I can have it – in my mind. Where fantasizing about having sex with your mother produces anxiety, because you know you’re not supposed to, fantasizing about having sex with a unicorn produces a pleasure unencumbered by the moral implications of actually existing objects. The same is true of sexting. It’s not like you don’t know you’re using a fake name. You’re using a fake name because that form of irreality comes with a distinct form of pleasure.

The opposition between physical sex and virtual sex is not an opposition between real and fake, between a true world and its pale imitation. It’s an opposition between being able to do something – to fantasize, to direct one’s own desires – and being unable to do something – having one’s desires limited and constrained by external factors. The pleasure of fantasy, its psychic value, is its promise of a space in which desire is unconstrained by reality. At its core, the difference between fantasy and materiality is not the kind of desire involved but its direction: “real” desire is directed outward; fantasy is directed inward. It’s an example of what Laplanche and Pontalis call “auto-erotism.” For the child at play, the child who “rearranges the elements of its own world in a manner of its own choosing,” fantasy offers an opportunity to imagine and to desire without the pesky constraints of reality. It’s not a failure to attain real satisfaction; it’s simply a real satisfaction that is oriented toward the self. Sexting isn’t a failure to locate a willing partner; there’s someone exchanging message with you, right? Rather, it’s an opportunity to get feedback on your desire; it’s a way of talking about yourself using naked pictures.

The moralizing view of sexting and virtual sex suggests that Anthony Weiner called himself Carlos online because he had to bury his shame in an alias, and in his specific case, as in many others, that might be true. But this is to ignore the fact that Internet aliases are assumed constantly by people who are neither married nor in public service, and, for that matter, by people whose digital activities have nothing to do with sex at all. It’s to ignore the pleasure of not being yourself, of assuming a new identity not because you have to but because it’s fun to pretend. “The opposite of play is not seriousness but reality.” The same might be said about the pleasures of kink; in most cases (but not all), bondage play doesn’t indicate that the person being dominated was unable to find an actual slave-master and settled for imitation sex-play instead.

What Jacoby and other post-Weinergate sexting alarmists fail to note is the fact that physical and virtual sex offer two fundamentally different experiences of pleasure. There’s a deep irony, then, to Jacoby’s decision to stage her argument against sexting in terms of empowerment: “A willingness to engage in Internet sex with strangers,” she writes, “expresses not sexual empowerment but its opposite — a loneliness and low opinion of oneself that leads to the conclusion that any sexual contact is better than no contact at all.”

Can this be true? Sure. Of course it can. It can be true. But it can equally be true that low self-esteem will drive you out of your home and into a dive bar where you’ll hook up with the first person you see, because you’re desperately hungry for any kind of physical validation from anyone at all. Low self-esteem is a phenomenon a lot older than the Internet. Jacoby insists that sexual behavior is a manifest sign of a latent sexual identity. Far from representing an investment in empowerment or the validation of pleasure, this conception of sex is deeply moralistic: Certain kinds of acts, this model argues, are performed by certain kinds of people. You’re not that kind of girl, are you? But, again, like low self-esteem, the moral policing of sexuality, and feminine sexuality in particular, is a lot older than sexting. That kind of girl has been around a lot longer than either cybersex or cyberspace. What kind of person would do something like that? this cri de coeur inquires. But sexuality isn’t about different kinds of people; sexual identities are just labels we stick onto behavior ex post facto. Rather, sexuality is about different kinds of pleasures, different kinds of actions, and different kinds of satisfactions. Sexting isn’t a failure to find genuine sexual satisfaction; it's sexual satisfaction of an entirely different kind.

Instead of trying to understand sexting in terms of what it’s not – instead of trying to understand it in terms of failure to be real sex – shouldn’t we instead try to grasp it in terms of its specificity, by asking what it does and what it is? The reality principle, after all, is not the only organizing principle of the mind; Freud is equally insistent on the existence of the pleasure principle, which pushes us to maximize pleasure and minimize unpleasure. What is the pleasure specific to sexting?

The pleasure of sexting lies precisely in its irreality, its origin and end in fantasy. It’s not a pleasure that imitates “actual” sexuality, but a pleasure that ignores the constraints and conditions to which “actual” sexual activity is subjected, in every sense. For one thing, sexting is a form of pleasure that transcends the spatial limitations of physical sex: It’s hard to have sex with someone in another country, but it’s pretty easy to send them a picture of your penis. It’s an activity in which desire orients action without the physical and ethical constraints of mutual presence. It’s a pleasure oriented fundamentally toward the self – and like all auto-erotism, it’s most fundamentally a form of narcissism. The pleasure of virtual sexuality isn’t about other people; it’s about the ideal sexual self that you can imagine for yourself if you don’t have to stop and account for all the ways in which you aren’t what you want to be. Laplanche and Pontalis put it well: “The ideal, one might say, of auto-erotism is ‘lips that kiss themselves.’ Here, in this apparently self-centered enjoyment, as in the deepest fantasy, in this discourse no longer addressed to anyone, all distinction between subject and object has been lost.”

It’s completely inane to imagine virtual sex as “arid zone of sex without sensuality” – neither fantasy nor pleasure can appear without a body to experience them, and, like every form of communication, sexting is contingent on a physical medium. Nor, for that matter, is there any reason to think that just because nobody else is touching you while you’re sexting, you aren’t touching yourself. Quite the opposite – sexting, like other forms of virtual interaction, is an opportunity to explore one’s body and one’s fantasies in an unobserved, unself-conscious manner, whether that means touching yourself in a way that you’d never touch yourself with another person in the room, or whether it means touching yourself while wearing a pair of old sweatpants that you’d never wear with another person in the room. Would Jacoby claim that an orgasm from masturbation is not a real orgasm? Or that masturbation is for people who lack the self-esteem to go out and get laid? While nominally argued from a concern for empowerment, Jacoby’s Op-Ed is actually staged in terms remarkably similar to “the double standard of sexual morality under which [she] was raised in the 1950s”: the standard by which any sexual act that is neither reproductive nor heterosexual is simply a deviation by degrees from true or real sexual intercourse. This is a moral and sexual standard that belongs to the 20thcentury, and to an age predating the invention of the text message.

Are there concerns raised by sexting? Of course there are, and the Weinergate scandal is sufficient proof. As our lives become more and more thoroughly enmeshed in the digital and as the digital domain is more rigorously policed, it becomes harder and harder to assume that our virtual acts will leave no trace on our physical lives, despite the thrill that this assumption offers. And just like “actual” sex, sexting can come to serve not as an alternative to reality but as an escape from it. And sure, it can be addictive and self-destructive; but so can shopping and fast food. Like the question of low self-esteem, the evident dangers and complications of sexting are less to do with the specificities of the act and more to do with our personal and social relationships to our bodies and our desires – relationships that are linked with technology and in a mutual relationship to it, but that predate our current era and will continue to organize our sexuality long after sexting has gone the way of video arcades and the telegraph.

Shares