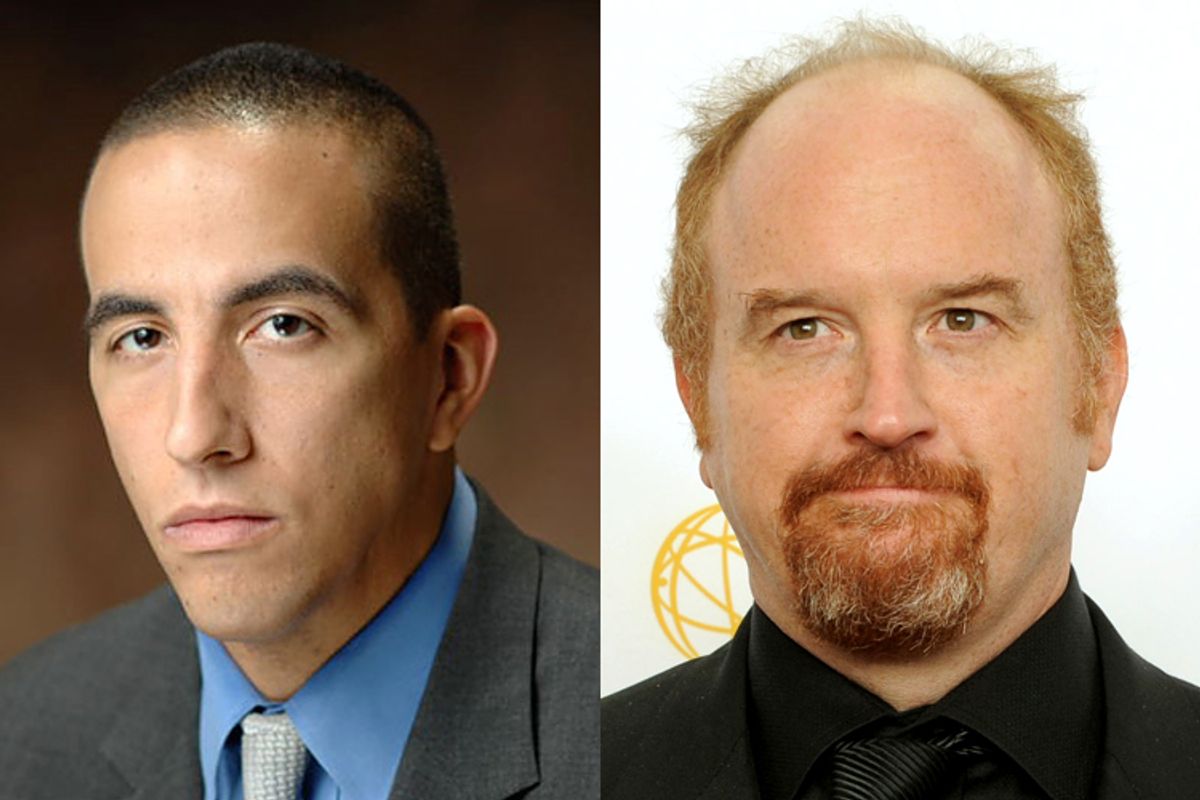

On April 23, 2013, a parody video appeared on YouTube, seemingly out of nowhere, which reimagined the comedian Louis C.K. as a recycler of classic jokes. Lines like "Why did the chicken cross the road?" were extrapolated into bizarre tangents that expertly mimicked C.K.’s cadence and mannerisms. The four-minute-and-eight-second video quickly went viral, racking up almost a quarter of a million views in a few days. Moreover, it drew praise for its spot-on impression and trenchant commentary from big-name comedians like Jim Gaffigan, Jim Norton and Amy Schumer.

The video was the brainchild of 34-year-old New York comedian J-L Cauvin, whose goal was not so much to skewer C.K. as it was to publicly question the comedy world’s hero-worship of him. The video, starring Cauvin made up with a bald cap and C.K.’s signature red goatee, solicited hundreds of YouTube comments and divided viewers. Many thought Cauvin’s impression was brilliant; others labeled him a bitter comedian who was piggybacking on C.K.’s fame as a means to bolster his own career. Even the popular comedy news website Laughspin.com took an implicit stand against Cauvin’s video, posting “Comedian mocks Louis C.K.” as part of its headline.

For a short time, Cauvin’s visibility within the comedy world blossomed. Opie and Anthony played the video on the air, and highly downloaded comedy podcasts discussed it in a positive light. Yet just as quickly as Cauvin’s name burst into the comedic zeitgeist, it soon receded, and Cauvin was back to his previous station as a 10-year veteran with a crushingly low profile.

Cauvin’s career, like all others, has had its ups and downs. After getting a law degree at Georgetown, Cauvin moved back to his native New York to pursue law by day and comedy by night. On October 3, 2007, he made his television debut on "The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson," turning in a more-than-respectable set at four and a half years in. Since that time, however, a career that seemed to have great potential has witnessed a steady decline, to the point that, as of August 2013, Cauvin is set to retire from comedy at the year’s end.

His trajectory is in some ways a sign of the times. Now that every aspiring comic has to be a social media presence, essentially giving away comedy for free online, it can be harder than ever to break through the crowd -- or to make ends meet.

Comedians come and go every day, so hearing of one’s retirement is rarely much of a shock. But over the past decade, Cauvin has been almost universally praised. New York comedian and national headliner Gary Gulman, 43, called Cauvin “excellent,” “incredibly talented” and “a great performer,” and the late Patrice O’Neal specifically asked for Cauvin to emcee a set of weekend shows for him in 2012. The natural question, then, is how does a comedian with more than enough skill to rival the never-ending slew gracing television screens get passed over by virtually an entire industry?

It’s a timely question, too, as the comedy world has been in a state of rapid expansion in recent years, entering something of a comedy boom. Thanks in part to Comedy Central — currently developing two new standup series in addition to the three it already airs — there's now a plethora of standup comedy available on TV.

But perhaps an even bigger contributor to the boom is the rise of social media. Over the past couple years, the overwhelming majority of working comics have taken to Facebook and Twitter to broadcast pithy one-liners, communicate with other comics, interact with fans and generally support their own careers. Many have also taken to hosting podcasts in which they interview fellow comics. Some have even starting using the nascent video-sharing service Vine, as well as Instagram, simply to keep churning out new media for a rabid fan base. And plenty of comics still use YouTube to create short sketches that showcase their acting and writing talents. Even Comedy Central has gotten in on the online action, hosting the first-of-its-kind Twitter-based comedy festival this past April.

While many comics enjoy these media, plenty use them simply out of obligation. One successful New York comic who’s had his own Comedy Central special told me, “I can be very honest in saying that if I didn’t have the priority of needing those things for work reasons, I would not be on them.” He then reiterated, “If I had my choice, I would not use them. I do not have my choice.” For working comics today, the use of social media is, with no exaggeration, imperative.

This is why, in recent years, Cauvin decided to take his act online. He maintains active Twitter and Facebook feeds, hosts a podcast, posts movie reviews and original sketches to YouTube, writes a blog and pens the occasional piece for The Huffington Post — all while still taking the stage most nights of the week.

It’s not what Cauvin necessarily wants to do, but it’s what he knows he must. After landing his Ferguson spot, Cauvin tried to advance his career via the old method: performing in comedy clubs in and out of state until someone would notice his talent and offer him an opportunity. Each year from 2008 to 2011, Cauvin added more bookings to his calendar and received more praise from peers and the powers that be. But in 2012, the trend reversed: the clubs stopped calling and the bookings became sparser. Seemingly writing for an audience that didn’t exist, Cauvin’s faith in the eventual success of his career eroded by the month, to the point that when I first met him, he was nearly convinced his career was over.

Throughout the decade that he’s done standup comedy, Cauvin has sacrificed his happiness for a chance at fulfillment. He abandoned a budding law career to focus on comedy full-time, he strained relationships by letting his comedy career take precedence, and he descended into bouts of despair as he watched younger, less-polished comedians advance past him. Even the proliferation of social media has done little to advance his career, save the five minutes of fame his C.K. video got him.

Moreover, his personal struggles propelled his onstage voice into darker, more serious areas. As his comedy became more personal, his lack of success became more disheartening.

“I’d like to feel like there’s some sort of growth happening,” Cauvin says. “But am I gonna be some guy who’s just plugging away and seeing no movement in his career?”

When Cauvin started performing during law school in 2003, he was unwittingly entering a business that was changing models. “Alternative” comedy had become an ill-conceived catchall label during the mid-to-late 1990s for any comedy that wasn’t comprised of merely setups and punchlines — for comedy that, it was thought, could not be performed in clubs. On New York’s Lower East Side, as well as all throughout Los Angeles, alternative shows were held in bars, basements and run-down performance spaces. These venues charged a fraction of what comedy clubs did, yet attracted big audiences nevertheless. Over time, the “alt” rooms proved that there was a newly-minted market for comedy, as well as legitimate competition for the high-priced comedy clubs. This gradually forced many club bookers to use more local talent instead of outsourcing precious stage time to out-of-town comics who needed money for travel and accommodations. This trend persists throughout much of the country to this day.

Alternative comedy did not kill the club system; it merely weakened it, providing the first true opportunity for comedians to circumvent the clubs and still gain industry recognition. That said, even after the turn of the 21st century, the path for up-and-comers was firmly established. Comedians knew what they had to do to make it, and if they were good enough, the odds were in their favor.

That said, the path to success is no longer as concrete as it once was.

That old path resembled a pyramid: everyone started at the base, and the better one got, the higher one rose, until only a few reached the top. When a club owner or booker recognized talent, he’d offer a comedian a gig as an emcee, hosting the nightly shows. The next step was becoming a feature, essentially an opener for the headliner. Becoming a headliner was the ultimate goal.

The path is still the same — novice, emcee, feature, headliner; it’s the process of getting recognized that is different.

One example of social media’s effect on the industry the case of Los Angeles-based Rob Delaney. Now 36, he’s been doing standup for just over a decade. Before 2009, he was performing around the country, “but not for enough money to live or support a family with.” At the beginning of that year, however, Delaney started using Twitter.

“I realized pretty quickly that it was for jokes,” he says. Thinking to himself how to best utilize the 140-character medium, Delaney began a concerted campaign to provide a Twitter feed that was comprised purely of jokes. He didn’t interact with other comedians, he didn’t link to interesting articles, he didn’t tell the world what he had for breakfast. Delaney gradually gained a sizable following (as of this article’s publication, Delaney has almost 900,000 Twitter followers) and is now a nationally headlining comedian. Asked if he can retrospectively envision success without Twitter, he pauses before flatly saying, “No. I can’t imagine any other way it would’ve happened.”

Delaney is, by all accounts, the exception, as few comedians have been able to use Twitter to directly change the trajectory of their careers. But the fact that social media can breed a national headliner is a radical departure from the hive of skinny ties dueling it out in front of brick walls in the 1980s and early 1990s. One either made it or didn’t solely within the confines of the dimly lit comedy club. Now, however, if used properly, social media allows the opportunity for anyone to circumvent the system and become a recognized voice — a thought that distresses the more traditional Cauvin.

“Comedians are born,” he says. “And I feel like we’re in an age now where people think comedians are made.”

Another example is Bo Burnham. In 2006, Burnham posted original musical comedy videos to YouTube. Less than a year later, he had representation. The following year, he performed at Montreal’s Just for Laughs comedy festival. And in 2010, he recorded a one-hour special for Comedy Central.

Burnham was born in 1990. When comedians were putting in their 10 years, sacrificing their happiness for a chance at the brass ring and enduring the unavoidable experiences of bombing onstage, Burnham was recording videos in his home, not even old enough to drink a beer at the clubs he’d never performed in. Comedians like Delaney and Burnham are the beneficiaries of comedy's new structure — talented individuals who expertly took advantage of a fluid system that is trending toward catering to the young and technologically proficient.

Although the rules have changed, the game remains the same, however. Comedians can craft funny Tweets and post videos to YouTube all they like, but if they can’t cut it onstage, the audience won’t buy it. To be a good comedian, you still have to put on a good show.

That said, with more media springing up by which comedians can disseminate their content, and a therefore ever-growing sea of up-and-comers, it is becoming increasingly difficult to stand out. And it's becoming well nigh impossible to do so without doing a certain amount of work for free online.

In 2009, veteran comedian Marc Maron, 49, launched the podcast "WTF with Marc Maron," which eventually propelled him from underappreciated “comic’s comic” to the star of his own television show, "Maron." In 2011, Pete Holmes, 34, launched his podcast, "You Made It Weird." Later this year, he will have his own television show on TBS. Also in 2011, Nikki Glaser, 29, and Sara Schaefer, 34, launched their podcast, "You Had to Be There." Earlier this year, the duo’s television show, "Nikki & Sara Live," began airing on MTV.

These comedians were all established names, to one extent or another, before their forays into podcasting, but it’d be difficult to argue that their ability to consistently showcase their talent each week to thousands of listeners, free of charge, did not directly affect their careers. At a minimum, the podcasts increased their fan bases; at best, they laid the foundation for television contracts.

The trend in comedians giving their comedy away for free is not new — as evidenced by the UCB controversy in late 2012, many comics occasionally perform sets free of charge — but it is becoming more and more pervasive. The modern world of standup comedy does not allow for most comics to dedicate all of their time to simply crafting new material. Even big-name comedians who came up before social media like Jerry Seinfeld, Steve Martin and Albert Brooks have Twitter accounts, which they use, in part, to keep their fan bases intact.

At the beginning of 2013, Cauvin made a decision that he would give his career one final year to gain traction. Not only did he continue to perform, but he also began generating online content at a rapid clip in the form of his podcast, YouTube videos, and blog and Twitter posts -- all content that's available for free. Yet with little forward movement in his career, and few prospects on the horizon, Cauvin doesn’t know how much longer he can do comedy. At some point, he needs to make a decent living. He wants to settle down and have an actual life that doesn’t hinge on the small and inconsistent paydays of standup comedy, let alone the nonexistent paydays of free online comedy.

“I want a wife,” Cauvin says. “I want kids. I want a golden retriever. Very simple stuff.”

When I asked people within the industry why a good comedian with a decade’s experience isn’t making it, they offered all sorts of reasons, no two the same. The reason, it seems, is there isn’t one. Some comedians make it and some don’t.

When I then asked these same people at what age a comedian should quit if he or she hasn’t made it, though, they did have a universal answer: if you truly want to succeed, if it’s really your dream, if it’s what you want more than anything, then you don’t quit. You keep going. A break can always come. There’s always hope and there’s always time.

But comedians quit every day, some more talented than others. The success not coming their way, they see no logical path to making it. Simply because outside forces have morphed the goal into a mirage, however, does not mean the drive was any less real.

“Maybe it’s okay to be a quitter,” Cauvin muses. “Why do we always tell people, ‘Don’t quit?’ What about sometimes just being a rational person and cutting your losses? We look at all the successful people that don’t quit, yeah, but we don’t hear about all the people who really went for it and didn’t make it. And maybe they regret that. I don’t want to be one of those people.”

“I’m an irrelevancy,” he continues. “I’d rather be an irrelevancy with a paycheck.”

Shares