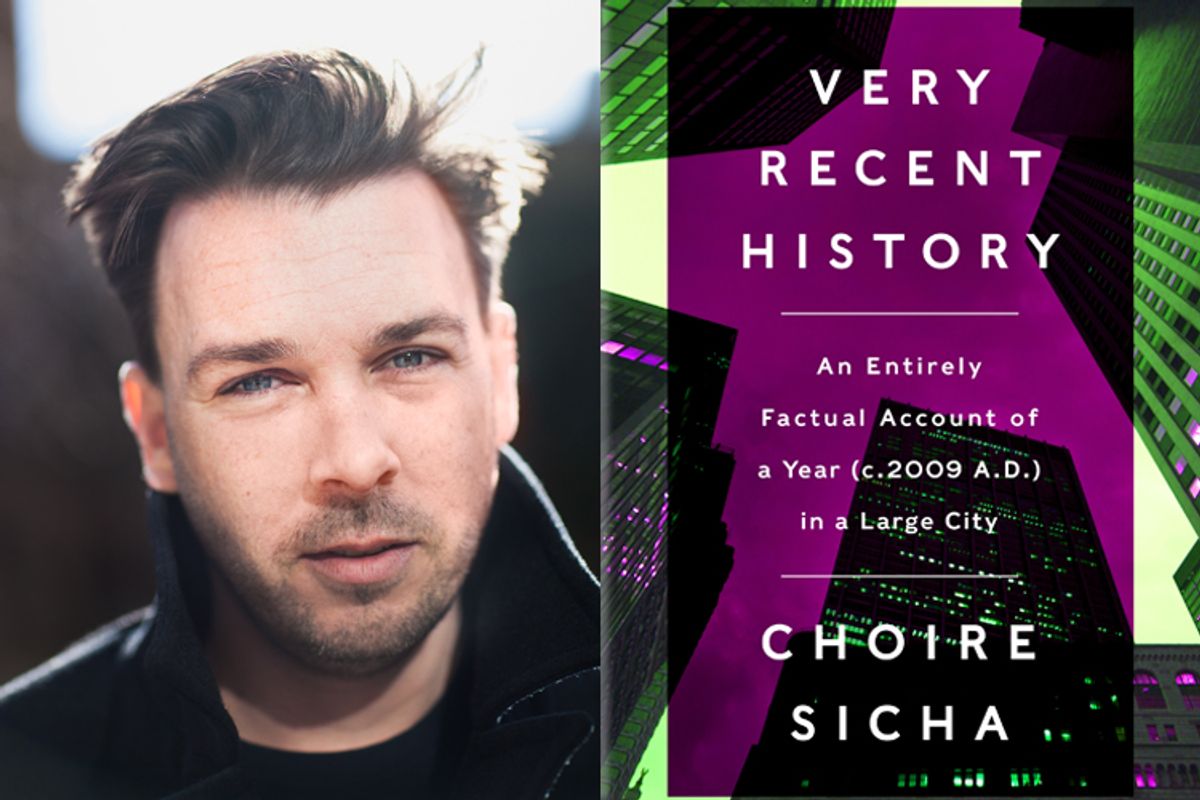

After years running a website, Choire Sicha is embarking upon a new career -- not that that's anything new for him.

Sicha, who was a gallerist before being hired to edit Gawker and, later, as a staffer at the New York Observer (and then at Gawker again!), is set to release a book-length work of reporting, "Very Recent History" -- all while co-editing the Awl with fellow Gawker refugee Alex Balk. Even while the Awl has blossomed into a network of sites including the Hairpin and the Billfold, Sicha has been revising "History," a book that breaks from the short-form, quickly disappearing form of the blog post. (Disclosure: I have worked with Sicha on freelance posts at the Awl, and like Sicha am an alumnus of the New York Observer.)

The book takes on the lives of a coterie of gay men attempting to build careers in the pivotal year 2009, a year during which Mayor Michael Bloomberg's New York, no longer quite teetering on the brink of disaster, seemed utterly closed-off to anyone without inborn social advantages. Men fall in and out of relationships even as their student loans only compound upon themselves -- and work continues to go nowhere. The names are, generally, changed -- but the events are all real.

Sicha's book attempts to explain 2009 as though he's writing for an audience in 4009: Everything from credit cards to time zones comes in for full explanation. But certain things are comprehensible to readers in any year -- for instance, protagonist "John," a corporate functionary, having a chemical breakdown on Fire Island. Sicha, who claims he began with many more subjects before winnowing the book down to "John's" clique, is preoccupied with the work of Janet Malcolm -- particularly "The Journalist and the Murderer," the nonfiction book that advises reporters that "Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible." How does that inflect a book about 20-somethings being followed by a reporter intending to turn their work into the Book of Our Time? Here, Sicha explains himself.

You’re recording this, too?

I’m too stressed out to only have one version.

That's probably a good idea.

I used to go to interviews all the time when I was going to meet famous people, because I would literally never see them again, and I’d be like, "Hi! Here’s both my tape recorders!"

So I read your book.

I’m so sorry. It’s short, at least.

Are you nervous about how you’re received?

No, I don’t really care.

Yeah, there’s a certain sublimity to it. Because, it’s a little soon to be thinking about the next book.

Oh, God, yeah. Makes vomiting motion. Actually, what’s nice is that I’ve heard from a few people who are like 25, 27 and whatnot, and they were really into it. And I’m stoked about that. That’s what I really want. But, like, that’s what I wanted. When 40-year-olds and 50-year-olds read it, I dunno if they’ll get it or care or whatever. And I don’t care or whatever. Fuck them.

How do you get it, though? You’re not 25 or 27 –

Very old. Exceedingly old.

Not exceedingly, but you’re a generation removed from the people you’re writing about.

Yeah, two-thirds of a generation. I mean, it’s close. Well, it’s funny, ‘cause you know, they’re all almost 30 now. So weird. What did I want to say about that … I mean, I was talking to one of the guys in the book, I was emailing him, and he’s a huge Janet Malcolm fan and so am I. I was literally like, "It’s only fair for me to say that this book is a huge work of projection." And he was like, "Well, of course it is."

And so in some ways: Why would I write about this? It’s because – it was different circumstances and a different time when I was that age but it sort of felt the same. I remember it pretty vividly, the parts I do remember.

It’s interesting, too, also, because it’s all about gay people, which I don’t think I realized when I was looking at the jacket copy. And though this book isn't, like, about DOMA, things have changed much more swiftly for gay people in the past generation than they have for straight people. If you were writing about straight people -- their rituals are still kind of the same. Has that been something you’ve had to deal with, trying to understand the courtship rituals of –

Of the young gays? Well, it’s funny, you wouldn’t know that it was about gay people, because the word "gay" isn’t on it or in it. I don’t think the word "gay" is used even once in the whole book, which is hilarious and weird. But yeah, it’s funny, I meet a bunch of gay kids all the time, like kids who are in college or whatever, and they are really different than me. A lot of them just don’t give a shit about being gay. They’re literally like, psh. Like they don’t, they do not care. They’re not even interested in it. And I don’t get that kind of gay, like that kind of gay I don’t understand.

You have this activist history, at least when you were younger.

Probably, yeah. Lazily. Off and on. But I mean, it was also really different from being – like, I was dating in 1984. I was a sophomore in high school, but I was dating. And that was just a fucking different time.

Right, I feel as though it’s in some ways gotten easier, but in some ways the lack of proscribed rules for how people can act has made it so much more open and in some ways more difficult, which your book deals with.

Yeah – a lot of gay guys don’t have to seek out a gay society, which in some ways is good, because then they don’t have to see creepy older men. But in some ways, it’s bad, because they’re living the same life as all their straight friends. And that’s a dissatisfying life.

Do you feel as though things are going to move more in that direction? That gay people are going to resemble straight people more and more?

Yeah, well, they haven’t totally given up, which is funny, because you go out – and you’ve seen this, probably – and there’s a lot of super-queeny young gay guys, and you’re like, why? Where are they getting this from? Where did they pick this up, and why are there still super-identified gay guys? And I’m not sure we ever really knew why there were those, but especially now it seems like there’s a much broader diversity of experience you can have. And people are definitely enacting that broad diversity of experience, but some are enacting a pretty traditional –

And it’s also like, what are you even referring to? Where did you find the DVD of Bette Davis to enact these things from 50 years ago?

But I guess some of them are watching "RuPaul’s Drag Race" or whatever. Which – good for them. So I guess there’s more media access, really. I think they’re, on the whole, probably much happier and healthier than we were, I think, although maybe not. In the big cities, who is, I guess?

I don’t think any of the kids are growing up in New York. They’re still binge drinkers and having unsafe sex, so …

Yeah, it’s kind of interesting that your book – not consistently, but in the Fire Island part – there’s a lot of binge drinking and drug use, but you convey it really dispassionately. Or, at least, you don’t jump in and say, “This is bad. I can’t believe how bad. How horrible.”

Yeah, I hope so. I didn’t want it to be … well, I also feel like when straight people read this book, they’re actually shocked. Which is hilarious, because straight people are easily shocked. They like being shocked. It’s fun for them. But I also just felt like, well, this is what happens sometimes. That was my experience. Like, “Oh, I ended up in a really tragic experience I shouldn’t have been in.” Like, again and again. It happens.

What are your feelings about young people, speaking very generally?

Young people generally? I have this crop of interns right now at work that I think are so charming. I just love them. They’re bouncy and interested in ideas and they want to have a good time and they’re probably a wreck sometimes and stay out too late but they’re smart and funny and they grew up with the Internet, which I didn’t.

It makes your mind work so differently.

And I think they talk about it in the book, they talk about – like, they’re all addicted to Gchat. They grew up with Gchat. So, like, it’s so unfair. I had chat rooms starting in my mid-20s, late-early 20s, so that helped. So I definitely get what that experience is like.

If I’m Gchatting a colleague or someone my very-specifically-own age, it’s like the most comfortable thing in the world.

I also feel like I have Gchat buddies who are out of my culture and out of my generation a little bit and it’s literally like -- they don’t chat right. They don’t know how to chat. They didn’t learn. And I will also say some of my interns and younger friends are a little more aggressive with chat than I am. I’m literally like – like, we cannot have an all-day conversation every day for our entire lives. There’s nothing more to say. Nothing.

And how I feel about the younger generation generally? I feel kind of good about them. They’re a little bit – the thing is, we were know-it-alls, as you are when you’re young, but we didn’t have anywhere to share that. So now everyone has everywhere to share that.

It's this weird conundrum that it’s actually very difficult to be a young person in this city because – it might be wiser to make all your mistakes in some weird, small town. Was that playing in your mind, that these characters should not be making these decisions on such a grand stage?

Yeah, that they should go home for a while, or go wherever they should go for a while? A little bit. Just partly because when I moved here, I didn’t make any money and I didn’t have to. I had a $300 bedroom in the East Village in Manhattan, so I made almost no money and it didn’t matter that much. But also you can get into a mess anywhere, but the other thing that happens too is that age changes so fast, because from the time I started reporting to the time the book came out and they finally read it, they were literally like, a) I don’t remember any of this, and b) I’m a totally different person. And they are. They’re totally different people.

Even leaving aside the fact that these people wanted pseudonyms for whatever reason, it just makes sense to use fake names, because to them it’s like reading about a fictional character, sure.

Oh, totally. I don’t even know how recognizable they think they are. And, like, so much changes in your life from your mid-20s to when you turn 30. Thank God I didn’t keep a diary or have a video so no one wrote a book about me. I was in my late 20s when I started blogging and stuff. I don’t want that shit out there. It’s a mess! It’s a mess.

Tell me about how you found the people in the book, and how you decided to start reporting on them.

I just kind of went out with different groups, met a bunch of total randoms. Literally, people I met at parties. Weirdly, when I sold the book, a couple of people emailed me and wanted to be in it. I was like, “No.” I immediately rejected them. I dunno why.

If you want to be in a book like this, it’s going to be performative; it’s going to be bad.

Right, exactly, it’s super-performative. I remember these girls emailed me in particular who were like, “Our lives are crazy!” Well, you should be on a reality show.

Go to MTV casting.

Which is – I mean, really, they might have been amazing. Maybe I’m a fool. The problem with having a book where most everyone’s gay is that all the characters are male. Which is hard on readers. Having the ability to divide up people by gender in your mind in a book helps you differentiate everyone.

It’s how sometimes I feel reading the novels of Alan Hollinghurst, too, which is like, OK, they all have to do with each other, and that’s great and also super-interesting: however, where’s my map?

Yeah, it’s like James, Jeff, John? Yeah, exactly. It’s all these dudes. That happens. It’s a hard thing. We talked a lot about, like, do we want to put a guide for people in the front, but those things don’t work on me at all.

Yeah, and also it’s a slim enough book.

Roll with it. Why were we talking about that? Oh yeah, finding people. I just like really interesting, random people, and there were two guys actually that I wish I’d followed. One was really out there and I didn’t follow him further because he wasn’t – I don’t want to say, it’s not that he wasn’t honest – he was self-aggrandizing in a weird way, and he was a little delusional. He was a little crazy. And it was really hard to untangle stuff with him, and I was literally like, I can’t deal with this.

Like, this is a totally different project.

And also, like, I can’t – you need a therapist more than you need someone writing a book about you. So I axed him pretty early. There was one guy I really liked. I wish I’d followed him and his friends, because he was really sweet and sort of sad. And actually he had a really terrible year that year – it was a really dramatic story, actually, so I missed out on that one. But yeah.

What’s the larger moral now that you’re looking at it, if there is one? There’s the argument that if you’re airing these people’s stuff out, there has to be a meaningful takeaway.

Oh, that’s a good question. That’s a really good question. I’m not very moralistic in any sense. I mean, there are some things I wanted to display. But I should have an answer for that, but I’m not sure if I do. Because I just sort of believe – I would like there to be more casual nonfiction in the world. I would like more little views into people’s lives. In an ideal world, if I had nothing else to do, I would like to put one of these out every 18 months – just a little tiny book about someone’s life. Know what I mean? About real people, because that’s sort of my interest in it.

And I’m obsessed with New York. I just wanted to write what New York felt like, really, because that was the initial conversation about the book that we had. And I just wanted to write down mostly about how fucking weird and shitty it was then, and just felt weird and shitty. Like, even if it wasn’t weird and shitty for some people, it felt weird for everyone.

Some of the problems described by the book have only gotten more entrenched: social divisions, the class problem. Does it feel that way to you?

No. It doesn’t feel – like, right now everyone’s in this weird thing. You know how we’re reading all these stories in the Times right now, like, “This 800-square foot apartment just sold for $600,000.” So this is what’s going on: All of these people are writing these stories because they’re waiting for the other shoe to drop, which is the subtext of these stories, and the context of these stories is they’re like: This doesn’t make sense. This actually isn’t a supportable real estate market.

It feels like tulip fever or something – houses aren’t tulips, but it feels like this manic thing.

No, it does! And it’s going to end soon in some ways, whether it ends rather casually because interest rates go up and people stop buying, or because people run out of things to buy, which they apparently have, in most of Brooklyn, at least. Then that’ll slow down. Instead of crashing, it’ll actually just slow to a less frightening level.

But there’s none of the whole – the mass layoffs have cooled down for sure, but it did get entrenched. The point is that this stuff did get entrenched. Now we know that employers don’t really care about us in the long term. We all learned that lesson. And I can look at BuzzFeed and be like, “This whole thing is horrible,” or I can say, “Hey, these people raised a bunch of money and are working hard to raise a bunch more money and they’re giving a bunch of people who I like, and a bunch of people who I don’t care about, jobs for a year or five years or 10 years, and maybe they’ll even get another equity in the end.” These people don’t view it as they’re going to work there forever either, they’re like, “Great, I have a job for a year or two.”

It's the alienation of labor: The readers of the book don’t have any idea what John, for instance, does. He could literally be doing anything.

Yeah, and it’s actually pretty interchangeable, I feel like, careers right now. The one thing I will say about gay people, and about people that I know and we know, is that a lot of us were excluded from lucrative career tracks partly by ourselves. I think that’s a little different with the really young kids right now, but if you look at real estate brokerage in the city right now, especially commercial property real estate brokerage, the industry is overwhelmingly white male heterosexual. And it has no barriers to entry. Any asshole can become a commercial property real estate broker. There’s no degree, there’s a state license, but it’s easier than the DMV test.

But almost no gay people go in the industry or get a foothold in the industry or even know that they can. No one tells us we can go into these macho industries. There’s a few gays in finance here and there, but we all become stupid things like writers who have no security or pay raises … it’s not like it gets better, as a writer.

It’s like, you continue oppressing yourself –

Kind of! A little bit! And I think part of coming to New York is that it helps people open their eyes to what they can be. Because if you come here and you’re like, “Who does this? How does X happen? How do you build a building? What is Wall Street?" you can actually go apprentice and go do that, and you don’t have to keep yourself poor. You know, if I was to do it all over again, I’d probably have a real job.

What would that be?

I don’t know. But I’m good with spreadsheets.

You had a real job – you were a gallery operator.

Sort of a real job! I should’ve apprenticed in that system – like, we just did it, because I had a rich business partner who gave me the money. I would’ve done better – I was just getting the hang of it for several years when we finally called it quits. It’s hard to learn.

Tell me a little bit about living in New York – it seems to be the right choice? You divided your time for so long between New York and Florida.

I did two years. Two years. It wasn’t that long. It feels like forever.

I’d been in New York for 18 years when we left for a while. I was one of those people who almost never left Manhattan, much less New York City. I didn’t drive for a long time, which helped. I mean, I never left New York. Then when we finally did, I was like, “I mean, it’s not terrible to get a break.” Except being away from New York is actually horrible for long periods of time. It’s not something you actually want to do, if you’re a person who’s suited for New York. And some people aren’t, that’s OK. So what’s my point here?

You tell me. Obviously it’s abysmal to be away for long periods of time, but in some ways it’s absent the very specific problems of New York. Or are they endemic? Did you encounter them again in Florida?

[I]n Miami, it’s like L.A. without the culture. It’s like a driving society, but with nowhere to drive to, basically, but it was also just recovered from the devastating real estate crash there, too. Like, it was horrific – the closures in Florida. Which made it really cheap, and it was actually really fun, but it was also really far away from New York, even though it’s not at all. So I guess I got some distance, which is nice. And it felt really temporary the whole time. It was good.

Tell me a little about thinking through blogging versus writing a book.

I know, right?

I can’t even conceive of switching gears like that.

Oh, it’s horrible. It’s really terrible.

Is it like, writing the book on nights and weekends, or …

I would take off time from blogging in binges, too, which was helpful. Spent a lot of time in libraries, which was weird.

Libraries are weird places. I’m glad they exist, but they can feel gross.

They’re really strange. It’s sort of like being on a subway car, in some ways. You’re like, “Hi, everybody. Yeah!” I was also like – it’s part of the reasons why the chapters are so short sometimes. Partly because I don’t like long chapters, but also partly because I kept – a lot of making the book was cutting away, actually, which I sort of learned from [the Hairpin founding editor] Edith Zimmerman. She writes by reducing – she writes stuff and takes things out and takes things out and takes things out, which I’d never really done. So that was something new I picked up. Also just the rewriting is so insane, which you don’t do with blogging. There’s so much rewriting.

Well, I feel like that has more to do necessarily with the publishing industry. It seems so antiquated in some ways.

Well, it’s so slow. You’re sitting there with a manuscript, and then they give you back an edit -- they’re like, “Get this back in three months.” You’re like, “Three months!” I’ll ignore it for a month and a half, I’ll look at your notes, and then I’ll get back to work. But can you imagine? So you’re sitting with this thing – so of course you start rewriting and rewriting and rewriting insanely, because it’s this thing that’s not yet published, which is so alien.

Do you think it’s possible to be a creative person in New York and not have a benefactor?

Yes. Yes. Absolutely. I really believe in working, and if you want to write, if you want to make paintings, if you want to make films, I do think – you’re going to be really tired, but you can work and do that stuff. I believe that. I mean, I wish I had a benefactor.

Like, your parents or something.

Yeah, I do think so. I feel like I’m listening to the kids right now really intently. Because I’m sort of like, how are you doing it? How are you managing it? How are you funding it? And they’re like, we’re doing it the really old-fashioned way. I’m going to live in a really shitty neighborhood as far away as possible, or I’m going to work this shitty desk job. It’s good for you. It’s good for your social skills, it’s good for your life experience, it’s good for your empathy. I remember there were arguments about this when I was young, I feel like [novelist and lesbian activist] Sarah Schulman used to talk about this: get a fucking job as a waitress, so you work four nights a week and make tips in cash and do your fucking plays or whatever when you can.

It really gets to the heart of – briefly – when people get really angry at any author or any actress or TV producer who’s 25 and doing it and has wealthy parents.

I feel like on some level, 1) people don’t know – people who come here don’t know a lot of rich people, because they haven’t been here long enough. I know a phenomenal number of extremely wealthy people, and that’s just from being here and going outside. In some ways you get acclimated to that, which is weird – but on another level – I just realized they don’t even have that much money, I mean they have more money than I do, but I don’t have any money. It sort of doesn’t matter on some weird level, and also there’s a lot of comparing our own experience self-pityingly with other people’s stuff. We do that with the Rich brothers [humorist Simon Rich and novelist Nathaniel Rich, the sons of New York Times columnist Frank Rich], we do that with ["Girls" creator] Lena Dunham and all these people. I’ve always objected to treating Lena Dunham’s parents like rich New York royalty.

That is an entirely different conversation. I actually once got in an argument with older people I know when they kept insisting Carroll Dunham [the contemporary artist and Lena Dunham's father] got her that show.

Carroll Dunham is a fantastic painter, and you know his paintings are worth a lot of money now, but it's not like her dad was George Soros. It's not like her dad was actually wealthy.

Or actually powerful either, in, like, a Michael Eisner sense.

Right. I've always said this is not like Cindy Sherman for one thing, and for another thing, I don't even know ...

Do you compare yourself against other people?

No, I stopped doing that a long time ago. Like, you do a little bit. You know, it's funny. We're doing – Caleb Crain has a book coming out at the same time. It's a novel, so I just got an email from him today that's like, "Come to my six readings and on my book tour," and literally I was like, "Fucking bitch," you know what I mean? But that's just … but I don't know, for all I know he did those tours all himself.

Sure, he might have put it together himself.

He's a literary novelist so I bet he did do it himself. So, there's a knee-jerk reaction that I have – that we all have – that totally makes sense. I mean I really push people a lot, like: If someone has something you want, go fucking take it. I don't want to say nobody gave me anything – people gave me a lot of things – people gave me jobs, people gave me food, people gave me a lot of things here, but a lot of it is just labor.

Do people give you stuff now, or do you see yourself as both self-made and continually self-making?

I think people give me things, I mean I kind of feel like, I'm actually happy that people are reviewing the book. There's no actual real reason that people should review the book. It's a small, weird, fucked-up book about weird things, and it's not traditional nonfiction journalism and it's not a novel, so I don't even know what to make of it. So I'm just proud of the fact that people are paying any attention. So, yeah. People in New York are nice. People want to collaborate with you.

How do you feel you are generally at helping younger people versus wanting them to kind of take it for themselves and make their own mistakes?

I'm so-so. Right now, I'm overtaxed at work so I'm not doing a very good job.

Because helping them isn't necessarily a good thing?

No, not always, right? I didn't tell anyone any — I mean I've had to do a couple of little things recently, like introductions or whatever, but you know it's honestly people give themselves opportunities if they ask. And then people like me, I'm not an asker, which is nice, because some people get that and take pity on me, but I've noticed more and more — so it's funny people running a publication, because you see who's assertive and who isn't. Certain people get things. Like, if there's anything I've learned recently it's sort of knowing what I want, and I'm not that assertive. Probably because I don't know what I want, so I don't know what to ask for.

Right. My next question was going to be "Have you gotten what you want," but …

I mean, I'm sort of like a weird, dumb, happy-go-lucky person, weirdly, put all my eggs and bullshit in, like … I mean, I've always been sort of like content that — like I'm always just sort of happy that I get to live in New York and I'm not out on the streets. I'm actually happy to live in New York just a little bit. It wasn't bad for my self-conception, but there was definitely a thing where sort of like, "Whoo, has everything really horribly gone wrong, finally?" I mean, no, it hadn't …

But there's that moment of fear. Like, I'm not me, or at least I'm not the me that I thought I was.

Living somewhere where I had no friends, could never make friends. And it's weird, I'm pretty social, but do I get what I want? No, I feel like I'm still stressed out in the same way I was when I was 18 in some ways. I'm always the one who's like, "What are we going to eat when we're old," is like my number one question. I worry a lot about getting old.

You mean, worrying whether there will be enough food in the cupboard?

Yeah, like, are we going to have enough food in the cupboard? Or … I mean, I've been worrying about that from day one – sort of like, what happens to me, so I'm not retiring any time soon, so …

Things at the Awl seem to be growing and flourishing. Are you planning more sites?

That's definitely something I want to do this year. One or two maybe. It's growing, yeah, it's actually been a pretty good year. I mean, things are healthy. We're a funny company. I'm really looking forward to hiring this editor-in-chief person to finally take over the whole thing, because Alex [Balk] is on vacation this week and we actually have zero staff right now.

But, it just reminds me again like, "Why do I want to do this?" I mean actually, I do kind of like doing it, but I don't really want to do it.

It doesn't seem like the whole grand plan from the beginning was to have like four or five sites.

Yeah, immediately we didn't really have a plan, so now we're growing up, which is sort of funny. Very slowly, but we're, like, growing up. We just want to be really sustainable and happy and we want people to do well. We're still a really horizontal organization and there's no fat, no one's time is — no one's sitting around on their ass — like, it's still pretty tight.

Did you ever imagine that you'd be running a company?

You know, it's sort of a joke, right? It's going to be funny when we hire an editor-in-chief because — we know this — we're going to have to make up our jobs, we're going to be like, "Well, what do you want to be in charge of?"

Like, "What do you want to do all day?" And I kind of know what we want to do all day, but then what else will I do? Like that seems so … I'm really scared … For the first month I won't be able to do anything, I'll be like, "I'll be around if you have any questions."

Shares