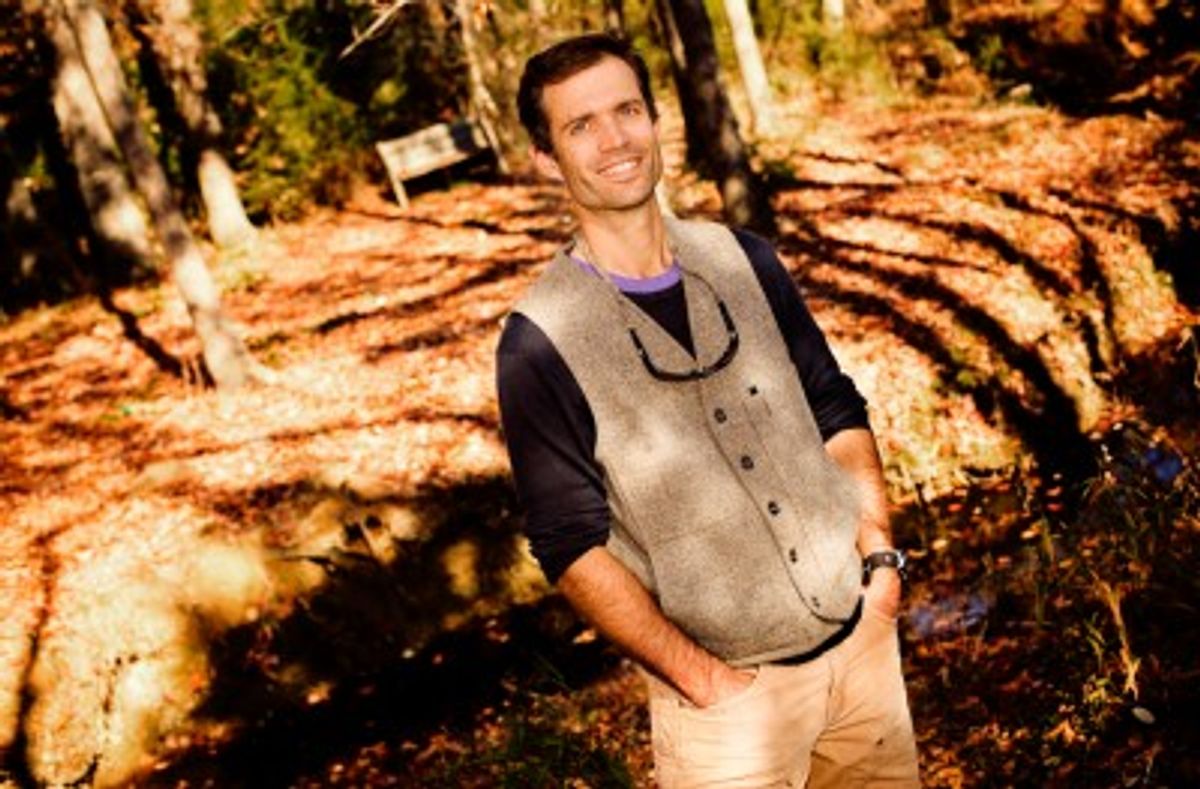

Gardens have had a place in the Judeo-Christian tradition from the very beginning, yet the organic food movement has more often been seen as a secular endeavor. Enter Fred Bahnson, "minister of the land," a Duke Divinity School graduate turned organic farmer who spent four years leading a community garden through his North Carolina parish. In his book "Soil and Sacrament," which came out this week, Bahnson explores the burgeoning "food and faith" movement, which approaches issues like organic agriculture, feeding the hungry and social justice from a spiritual perspective. “The command to care for soil is our first divinely appointed vocation," he writes, "yet in our zeal to produce cheap, abundant food we have shunned it."

Bahnson spoke with Salon about his book and the connection between what we eat and what we believe. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What would you say is the essence of the food and faith movement and what do you mean when you say it could change the food system?

I think the essence of the food and faith movement is about connection. It's about reconnecting with the sources of our food, it's about reconnecting with each other through community, and it's about reconnecting with our faith.

Obviously that implies disconnection in all those areas. Speaking of the larger food movement, I think that sense of wanting that connection is also true. But I think the larger food movement stops short. Yes, we need to switch from industrial to organic agriculture; yes, we need healthy food access in food deserts; we need food sovereignty rather than a corporate-controlled food system. But what’s missing is a recognition that food is intimately connected to our spiritual wellbeing as well, and unless we acknowledge that, we’re going to end up having truncated conversations.

We are not just hungry bodies here to feed ourselves good food; we have a deep spiritual hunger as well, and too often that gets ignored. We all hunger for more than just a full belly. Religion is so politicized in this country that people are leery of talking about it. Yet it’s such a huge part of so many peoples’ lives, whatever their tradition happens to be. This food and faith movement is an indication that people want a more holistic life. Many of those I’ve come to meet in the food and faith movement view soil as a sacrament: a physical manifestation of Divine grace. They know that the way we eat is intimately connected with our spiritual hunger. Our hunger for meaning, hunger for understanding what we're doing here on this earth, what we should do with our lives. All of that is intricately bound up in how we eat.

The food and faith movement arises out of this hunger to reconnect on multiple fronts, whether it’s people working on hunger, health, agriculture or climate change. Food is simply the overarching metaphor that pulls all those different threads together into a coherent whole. Particularly in Chrboistian and Jewish communities, which I wrote about in the book, food is a central metaphor of the faith. For Jews, it's the Passover meal, it's Shabbat —the Friday evening meal every week. For Christians it's the Eucharist, the Lord's Supper, and both of those meals are powerful, powerful metaphors that, when we start to pay attention to them, really help us think through the way we eat: where our food comes from (is it a commodity or a gift?), how we share food, who gets to eat enough and who doesn't, who eats too much of the wrong kinds of food, who even gets a place at the table.

Your philosophy is centered on looking at agriculture as greater than the sum product of the crops grown. What kind of pushback have you experienced from conventional farmers, and why do you think that's the case?

In the book, I write about a farmer named Donny. I was starting a community garden for this little Methodist church back in 2005, and Donny was a tobacco farmer in the church. He thought our location for the garden wasn’t any good, because the soil was too heavy. His mentality was: The soil is basically a place you stick your crop, where you feed it fertilizers and pesticides, and the only requirement of your soil is that it be well-drained. My mentality was that you start with what soil you have and you build from there. You don’t grow crops; you grow soil. The soil is a living entity. It's something that requires care and nurture, just like a child. It's a biological being, and to produce good, healthy food, you have to build good, healthy soil. You can't feed it fertilizers and pesticides.

In the book you also describe how a group of people in your church opposed the community garden.

A small, but vocal group in the church initially opposed it. It was a difference in outlook. They really saw hunger as, you know, you give away some canned corn during the annual food drive and you’ve done your job. There was one person who, when we got a grant for the community garden said, "Oh, why don't you just take all that money, buy a bunch of food and give it away? Why waste all the time doing a community garden? It's so inefficient."

And what's the response you give when they ask you something like that?

I say that a garden is about much more than just feeding bellies. These church gardens and food ministries that are cropping up around sustainable food, they're growing a lot more than kale. They're growing community, they're growing healthy kids, healthy relationships, they’re reconnecting people with God’s creation. They are helping peoples’ faith become deeper, more ecologically mature, more holistic. There are a lot more crops coming out of the church garden than just tomatoes and zucchini.

Some of the similar farms that you visit start out with the church affiliation, but then eventually morph into something that's less spiritually defined. Do you think that having a specific connection to Christianity is important?

I don't want to limit it and say that it has to be connected to Christianity for it to be important. I think that one of the great gifts of the larger food movement is showing churches and faith communities what's possible in terms of how to grow and share healthy food. And so I'm not engaging in Christian chest-thumping.

One of the projects I wrote about, The Lord's Acre (the one you're referring to) is a really fascinating example. Several churches started this amazing garden ministry, but other folks in the community who are not part of the church quickly got interested and took ownership of the project. Now it's very much a shared project, it's a community project. And as Pat Stone, who I quote in the book, said, churches are always wanting to bang the Christian drum and say, “Well this is a Methodist project” or “This is a Presbyterian project.” But I think the beauty of a place like the Lord's Acre is that a church or two may help start something, but it quickly becomes a community project.

That's very much what we saw at Anathoth Community Garden, where I worked for four years. Only a small portion of the garden members were members of the Methodist church. Most people were either from other churches or from no particular religious affiliation. I really see this food and faith movement as a healthy way for communities of faith to engage people outside of their tradition in a way that's non-threatening to both parties. It's non-threatening for someone who's not part of any faith tradition to come to a community garden. Somebody who may never set foot in a church will feel a lot more comfortable in a garden and can interact with church members or other folks there. Likewise, it pushes churches and it pushes communities of faith to get outside their walls and engage with the world.

In the book you write: "The front lines of sustainability should be led by those most wounded by the system." Can you talk a little bit more about what you mean by that, and about the relationship between organic agriculture and social justice?

That line, I quoted a guy named Bob Ekblad, who started this really amazing ministry called Tierra Nueva out in Washington state. Bob and his colleague Chris Hoke work with those they call "people on the margins": those struggling with addiction, people in gangs, people in jail, migrant workers, people who I’d call outliers on the bounds of respectability. Many times, those are the ones that have been wounded by the system, which is how they ended up where they are. But rather than seeing those people as derelicts or losers or people to simply be warehoused in big prisons, Bob and Chris see those people as tomorrow's leaders, especially in the area of sustainability.

Bob and Chris’s critique of the sustainability movement is that it's too white, too middle class, and it really needs to be led by folks like Bones. He’s the guy I met who's in prison now, but who has incredible leadership skills. Bones was a former gang leader in the Skagit Valley. Chris Hoke has have been working with him to develop this vision he has. When he gets out, Bones wants to start a farm called "Hope for Homies." He wants “homies” who haven't really had a chance in life to come out and live on his farm, learn some agricultural skills, learn some life skills, and learn how to become leaders in the sustainability movement. To me, that's one of the most exciting stories I tell in the book because there's just so much potential there, just thinking about how many more guys like Bones are out there, being warehoused in prisons, and I’m struck by all that talent going to waste. There's just a lot of opportunity there for the sustainability movement to embrace people with a troubled past and train them up as tomorrow's leaders.

I'll give you another example: Zach Joy, who I write about in the book. Zach was a former crystal meth cook and after meeting Bob and joining Tierra Nueva, he is now their chief coffee roaster. I love that transfer of skills — it's not like Zach had to completely leave his past behind, he just used those same cooking skills and directed them towards better ends.

The communities you visit in the book have all worked really hard to achieve their own little versions of paradise. What's the key to sort of growing this movement and making its influence resonate more widely?

That's actually what I'm trying to do with my new role at Wake Forest University School of Divinity. I’m the director of a fairly new project called the Food, Faith, and Religious Leadership Initiative. What we’ve realized is that this food and faith movement is not yet a cohesive thing; it's an amalgam of lots of different faith communities doing lots of really creative projects. But they’re mostly disconnected from each other. What's lacking is a kind of central unifying vision. My work at the Initiative is to convene these different groups and help them develop one. We’re bringing together religious leaders—mostly Christian and Jewish—to talk about how to take this movement and make it into a more of a cohesive force for the common good.

We’re at the beginning of a wave. We have all these different communities doing amazing projects like Tierra Nueva, Anathoth and The Lord's Acre. The work now, I think, is to convene faith leaders and have a conversation about what that unifying vision will be. Our role is to equip them to create more redemptive food systems so that, as our mission statement says, “God’s shalom becomes visible for a hungry world.”

Shares